Venture Capital Investments – Australia

Industry Overview

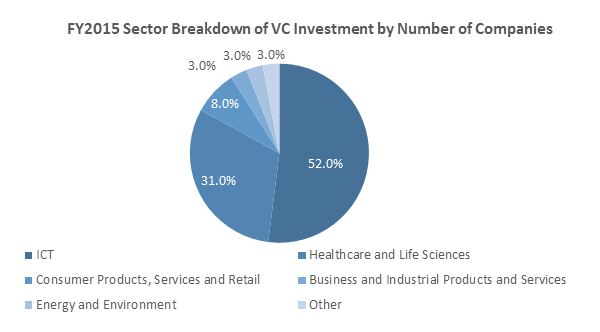

Despite Favourable Environment, Australian VC Market Remains Underdeveloped Compared to PeersDespite a favourable environment featuring a strong market-based economy, robust financial framework, and high-quality education system, the Australian venture capital (VC) industry has not been able to tap into its full potential. This can be attributed to several factors, including a lack of government support for the innovative sector; poor commercialisation of the R&D sector; cumbersome legislation surrounding innovative industries, for example regulations pertaining to ESOP schemes, and insufficient tax incentives; and conservatism among Australian investors leading to a paucity of capital, particularly in late-stage VC funding. As of 2015, high-growth technology companies contributed only 0.2% to Australia’s GDP. Past government efforts to boost the industry, such as the Innovation Investment Fund (IIF) established in 1997 to create domestic VC funds, saw limited success, leading to the scrapping of the program in 2014. In 2014, the previous government under Tony Abbott introduced budget cuts for the CSIRO, the country’s leading research institute, further highlighting the government’s poor commitment to innovative industries. However, recent macroeconomic shifts such as the end of the country’s mining boom, weakness in key commodity export markets such as China, and fears of a possible housing bubble have prompted the newly elected Turnbull Government to shift focus toward innovative industries – particularly in the ICT and health sectors, which accounted for 52% and 31% of VC investment respectively (based on number of companies) in 2015. In December 2015, the government published its National Innovation and Science Agenda (NISA), under which it has pledged to improve commercialisation of the country’s R&D sector; streamline regulations and improve taxation frameworks in the innovative sector; and introduced several schemes to encourage a higher amount of VC investment in the country from both foreign and domestic investors. In line with these recent developments, the Australian VC industry has also seen an increase in interest from previously conservative institutional investors such as superannuation (pension) funds. Super funds represent a huge pool of potential capital, with around AUD 2 trillion in assets as of 2015. The combined improvement in both government and investor attitudes bodes extremely well for future growth in the Australian VC sector. Shift in Focus toward Innovative Industries Driven by Looming End of Resources Boom, Fears of Property Bubble and Uncertain Future in Major Export MarketsThe Australian economy is vulnerable to a number of risks. Firstly, its status as a capital-importing country means that it is highly influenced by fluctuations in overseas markets. Second, Australia’s banking system is highly concentrated. Each of the four major banks (Australia and New Zealand Banking Group (ANZ; AUS), Commonwealth Bank of Australia (CBA; AUS), National Australia Bank (NAB; AUS), and Westpac Banking Corporation (WBC; AUS)) have large offshore funding exposures and are heavily exposed to developments in the housing market. Third, according to the Financial System Inquiry commissioned by the government in 2014, Australia faces lagging productivity growth, due to a combination of high wage growth from the resources boom coupled with an ageing population. For many years, the Australian economy has been overly dependent on sectors such as resources (e.g. mining); export of commodities (e.g. the export of iron ore to China); and real estate investment. The lag in the mining sector has been well-documented (a 2015 report by BIS Shrapnel estimated mining investment in Australia to drop 58% over the next three years); in addition to weak demand in China affecting iron ore exports (on 8th December 2015, iron ore prices dropped to a 10-year low; recent figures recorded a 5.6% yoy drop in Chinese imports); and what many believe to be a property bubble soon to burst (in 2015 investment bank Macquarie (AUS) forecasted a 7.5% quarter-on-quarter fall in house prices beginning from March 2016). Faced with these dangers, it has become more crucial than ever for the country to turn its focus toward new businesses and new technologies — the so-called innovative sector — in which venture capital funding plays a fundamental role. According to a 2013 study commissioned by Google Australia, high-growth technology companies could potentially contribute up to 4% of the country’s GDP (or AUD 109 billion) from the current 0.2% by 2033. However, urgent measures must be taken by the government in order to overcome the numerous challenges strangling the industry at present and capitalise on the sector’s latent potential. |

Venture Capital Funds Take Form of VCLP, ESVCLP or AFOFIn Australia, venture capital funds are registered with the regulatory body Innovation Australia. They may take the form of either a regulated venture capital limited partnership (VCLP); an early stage venture capital limited partnership (ESVCLP); or an Australian Venture Capital Fund of Funds (AFOF). There are currently 12 registered ESVCLPs and seven conditionally registered ESVCLPs, while there are 40 registered VCLPs and four conditionally registered VCLPs. There is only one currently registered AFOF. Each type of fund must meet certain criteria, outlined below:

|

|

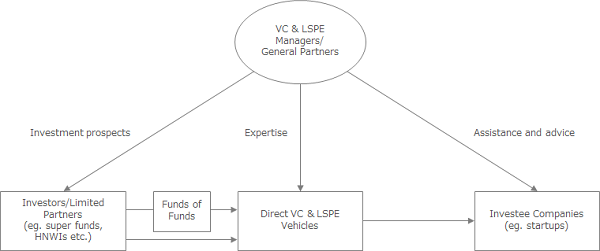

Structure of Australian VC & LSPE Industry

Source: ABS

Note: LSPE = Later Stage Private Equity |

|

Australia Boasts Strong Research Culture and Significant Investment into R&D, However Commercialisation of New Technologies Remains Poor The healthcare and life sciences sector plays a significant role in the Australian VC industry. The sector was the biggest contributor in terms of amount divested at cost in 2015, with a 38% share. It also contributed 31% of total VC investment in 2015 based on the number of companies receiving funding. In addition, roughly 25% of healthcare companies currently listed on the Australian Stock Exchange (ASX) received venture capital backing in their startup stages. Some examples of prominent healthcare businesses that have grown from early VC backing include Cochlear (AUS), Spinifex (AUS), Hatchtech (AUS), and Nitro (AUS). In order to ensure the success of such businesses — and thus a healthy rate of return for investors — a good rate of commercialisation of new R&D technologies is crucial to VC firms investing in the healthcare and life sciences space. According to Bill Ferris, founder of Australia’s first venture capital company and recently appointed chairman of Innovation Australia, Australia ranks somewhere between third and fourth in the world in terms of health and medical research, and also ranks highly in other research fields such as astronomy, environment, agriculture, engineering, information and communications and renewable energy. Australia’s higher education expenditure on R&D as a proportion of GDP is above the OECD average, and the country ranks highly in terms of research quality and output. However, according to the Global Innovation Index 2014, Australia ranks lowest among OECD countries on the rate of collaboration between researchers and firms, indicating the poor commercialisation of its R&D sector. The collaboration rate between researchers and large companies was 3%, which was far below the OECD average of 37%; for small to medium enterprises (SMEs), it was 2% compared to the OECD average of 14%. The reason for this poor commercialisation is largely due to a lack of communication between researchers and industry, as well as differing motivations and expectations. As announced in the 2015 NISA, the Turnbull Government has pledged to take the following initiatives to help improve the rate of R&D commercialisation in Australia:

VC Fundraising vs Research and Innovation Metrics (2014)

Source: Austrade, WEF, AVCAL |

Improvements to ESOP Legislation Expected to Help Startups Attract and Retain Top TalentThere are several challenging factors for startups looking to establish themselves in the Australian market, including a lack of access to capital, lack of government support, and the high costs of running a business in the country due to the combined effect of strong wage growth, high energy costs, and high transportation costs. In addition to these, one of the biggest hurdles for startup growth in Australia is the paucity of skilled talent available. Due to factors such as the poor commercialisation of R&D in the country as well as the burdensome regulations surrounding ESOP schemes, many successful Australian startups struggle to recruit local talent. In the Startup Muster 2015 report, 42% of startups cited a lack of available technical talent as their biggest external challenge. The lack of strong relationships between higher education institutes and corporations results in many promising graduates working for overseas MNCs rather than home-grown domestic companies. For example, in 2014, more than half of the participants in telecommunication giant Telstra’s (AUD) Cyber Security Challenge – a competition designed to locate the best cyber security talent in the country – opted to work offshore for multi-national technology companies, rather than seek employment in Australia. As such, many domestic startups are driven overseas in search of talented employees. An Employee Stock Ownership Plan (ESOP) is one of the most common ways for startups to lure and retain talent as well as boost employee productivity, since the value of each employee’s stake is directly tied to the success of the company. However, as of 2015, 41% of Australian startups had no employees with equity or options. This is because ESOP schemes in Australia have traditionally been burdened by complexity, cost, and the unreasonable tax treatment of options, whereby options are taxed at the time they are provided to the employee rather than when they are exercised. Many Australian entrepreneurs have said that the tax treatment of ESS options has reduced their ability to find talent in Australia and eventually pushed them to move operations overseas. Thus, in order to retain talented Australian entrepreneurs and generate a strong pipeline of startups, the Australian Government in 2014 announced a series of measures to improve the taxation scheme on ESOPs, including:

Additionally, as part of the December 2015 NISA, the government announced several further reforms to improve the accessibility of employee share scheme legislation. Under the new rules, companies will now be able to offer shares to their employees without having to reveal commercially sensitive information to their competitors. Visa Reform Aimed at Pulling in Offshore Investors and EntrepreneursThe Significant Investor Visa (SIV) was introduced to fuel investment from overseas investors in innovative sectors as well as enhance commercialisation of Australian R&D. As part of the minimum AUD 5 million worth of complying investments required over a four-year period, the visa also requires applicants to invest a minimum of AUD 500,000 in qualifying VC and growth PE funds (or qualifying funds-of-funds). Until recently, the Australian SIV was found to lack competitiveness compared to other countries with similar investor visa programmes due to cumbersome application process coupled with a high minimum threshold. Thus the government in 2014 proposed a series of reforms for the SIV, including a more streamlined application process. In 2014 the government also introduced a Premium Investor Visa (PIV), which offers a fast-tracked 12-month pathway to permanent residency for those contributing a minimum of AUD 15 million. Additionally in December 2015, as part of the National Innovation and Science Agenda (NISA), the government introduced an entrepreneur visa in order to attract potential overseas talent to the country. These measures should serve to encourage further investment from overseas as well as bring HNWIs into the country. There is also reform planned for the existing 457 skilled migration visa, which, along with the previously mentioned ESOP reform, should help to increase the pool of talent available for local startups. Given that migrants have relatively high levels of education, with 26.5% of Australia’s overseas-born population holding tertiary qualifications (compared to only 17% of the Australian-born population), it can be expected that such efforts to increase skilled migration will contribute significantly to human capital development and technological progress in the Australian workforce, and thus spur further development in the innovative sector. |

Recently Announced Tax Incentives Bode Well for Previously Neglected Startup SpaceIn the past, the Australian government focused tax breaks on favoured industries such as the resources sector and property investment whilst neglecting tax incentives for the innovation sector. For instance, in 2015, NATSEM estimated that Australia currently foregoes AUD 3.7 billion in revenue each year to negative gearing of residential property (a number which reaches AUD 7.7 billion when combined with the discount on capital gains tax). Although VCLP and ESCVLPs had previously been eligible for a number of tax incentives, such as an exemption from capital gains tax (CGT) for eligible VCLP foreign investors under certain conditions and total exemption from tax for investors in an ESVCLP, this had proved insufficient to attract investment in the space. The new Turnbull government has recognised the need for improved tax legislation in the venture capital space and announced the following additional incentives under the NISA:

Australia’s Risk-Averse Investing Culture Discourages Startups and Stunts Growth of VC Industry In general, venture capital is a high-risk high-return business, and companies operate under the assumption that the majority of startups in their portfolio will fail, where these failures will be offset by one or few big successes. Around 90% of returns will come from 10% of startups in a typical portfolio. Further, most VC funds have a 10-year timeline, meaning businesses must achieve growth fast. For this reason, it is vital for startups to have lofty ambitions and look toward global markets in order to achieve a sizeable market cap of at least AUS 1 billion. Likewise, increasing the total number of startups is critical in order to increase the potential number of deals that can be invested in. Australia fails on both these fronts due to its risk-averse business culture, which can be put down to a number of factors. Firstly, the size of the Australian market is small compared to countries such as the USA, which have a thriving startup ecosystem and can thus afford a higher rate of failure. The Australian tech startup ecosystem is still in its nascent stages, and as a result many startups founded in Australia are focused on small niche or domestic markets. There are relatively few disruptive, ambitious startups looking to global markets—27% of Australian startups estimate their market value at less than AUD 10 million, which is a far cry from the ideal AUD 1 billion. Secondly, Australia’s insolvent trading laws are among the strictest in the world. Up until very recently, Australian company directors were personally liable for payment of compensation and risked a pecuniary penalty order and/or disqualification from managing a corporation if their firm encountered financial difficulties. This served both to discourage entrepreneurs from taking risks with their businesses and deterred potential investors from joining as company board members. However, Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull recently announced reforms to insolvency laws as part of the Government’s Innovation Statement, released in December 2015. The reforms include a reduction of the default bankruptcy period from three years to one; protection of directors from personal liability for insolvent trading if they appoint a restructuring adviser to develop a turnaround plan; and a ban on ‘ipso facto’ contractual clauses that allow an agreement to be terminated solely due to an insolvency event if a company is undertaking a restructure. Alleviating the pressure placed on directors should help to foster more ambitious attitudes among Australian entrepreneurs, and thus encourage an increase in the amount of high-risk VC investment. |

Traditionally Conservative Super Funds Increasingly Eye Investment in VCAs of 2015, the Australian superannuation system (equivalent of pension funds) has accumulated over AUD 2 trillion in assets. It is the second largest part of the country’s overall financial system and represents a huge pool of capital. Super funds could play a vital part in the context of providing much-needed late-stage funding, especially since traditional bank lending via business loans is ill suited to the high-risk nature of startups. Up until recently, however, super funds have been hesitant to invest in high-risk ventures. Reasons for this include the current framework of the superannuation system, which is geared to a one-side focus on fees rather than considering net returns to fund members; and a perception that domestic startup industry is not successful enough to justify the risks associated with VC investment. Indeed, the Australian VC industry has in the past had a poor track record both in terms of exit opportunities such as through successful IPOs and a low rate of return for investors — according to 2008 AVCAL data, Australian venture capital funds formed between 1985 and 2007 had a pooled internal rate of return (IRR) of -1.4%. Further, the Australian VC industry is burdened with cumbersome regulations which further discourage super funds from investing in unlisted high-growth businesses. For example, super funds are currently required to publicly report the market valuation of their unlisted investments into venture and private equity. Despite these challenges, there has been a recent opening up of superannuation funds to the VC industry. Superannuation funds were the biggest contributor to the significant increase in VC fundraising witnessed in 2015, accounting for 60% (over AUD 200 million) of the total VC fundraising for the year. This was due primarily to the newly established Brandon Capital Partners’ MRCF3 fund, which pooled capital from four major super funds for investment in the medtech sector. Equity Crowdfunding Eyed as Boost for Early-Stage Capital; However, Recently Proposed Government Initiatives are DisappointingAnother significant challenge facing Australian startups is the lack of available capital. In 2014, it was reported that only 33% of Australian startups received external funding, with 61% coming from private capital. Meanwhile, 66.8% of startups surveyed said they required funding to continue doing business into the following year. In December 2015, the Australian Government introduced legislation to enable the participation of retail investors in equity crowdfunding, which is estimated to increase the amount of available capital by AUD 300 million over the next 3 years. The Government recognised the development of a crowd sourced equity funding market as an urgent priority in order to support the funding needs of early stage innovators. However, the proposed legislation has received backlash from the Australian startup community. In effort to protect investor interests, the legislation mandates that only public companies with annual turnover and gross assets of less than AUD 5 million will be able to access crowdfunding. Going public is an arduous process and not a realistic option for many startup companies. As a result, startups must first become “exempt public companies” to be able to utilise crowdfunding, and will eventually be required to become full public companies after a set period of time. This will mean startups themselves will end up bearing excessive administrative and compliance costs, rather than crowdfunding platforms such as VentureCrowd (AUS) or unit trusts, and restrict access to early-stage capital. Moreover, under the current laws, equity crowdfunding is restricted to sophisticated investors with more than AUD 2.5 million in investable assets or annual earnings of more than AUD 250,000. These proposed changes again highlight the risk-averse culture in Australia, with the tendency to impose cumbersome regulations in order to “legislate the risk” out of business, which in many cases actually serves to stunt the growth of new businesses. |

Growing Gap between Early-Stage and Later-Stage Funding Pushing Promising Startups OverseasThe lack of funding for later VC rounds is even more conspicuous than the lack of capital for early rounds. In 2015, only 16% of companies saw investments at the later VC stage. This gap is pushing many growing companies wishing to scale up and expand their businesses overseas in search of capital, or else look toward offshore venture funds. One notable case of this is successful Australian-born tech startup Atlassian (GBR), which moved its headquarters from Sydney to London in 2014. Atlassian is well-known for not receiving outside funding until 8 years after its founding — even then, the investment was made by Silicon Valley-based Accel Partners (USA), rather than a domestic VC firm. The company has stated that it will likely not list on the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX) in future, citing a lack of knowledge or support from local investors for technology companies. Late-stage funding is vital for fuelling economic activity, since the scaling up of businesses has a number of positive side effects such as the creation of new jobs and an increase in the leasing of office space. Thus, further effort is required to boost late-stage funding and encourage domestic startups to keep their operations onshore, such as the creation of government co-investment funds and greater contribution from institutional investors. VC Funds Raised by Investment Stage in FY2015 (AUD Million)

Source: AVCAL

Note: No. of funds raising capital includes all funds with first, intermediate or final closings in FY2015. |

Market Trends

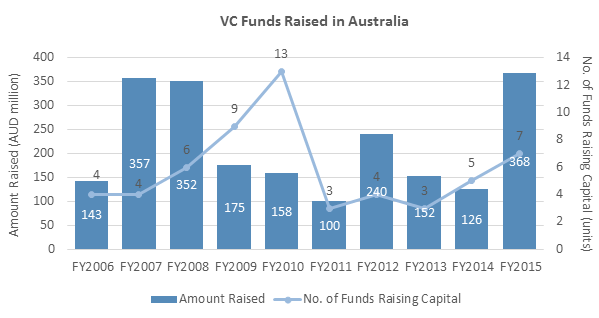

Significant Increase in VC Capital Largely Due to Entry of Super FundsIn 2015, VC fundraising in Australia reached a total of AUD 368 million. VC investment fell 58% year-on-year to AUD 224 million in 2015, although this figure was still higher than the 10-year average of AUD 203 million. The boost in the VC industry in 2015 in terms of fundraising can be largely attributed to the establishment of three large super-backed funds – from Blackbird Ventures (AUS), Brandon Capital Partners (AUS) and Square Peg Capital (AUS) – each of which accumulated a total capital pool of AUD 200 million. As of 30 June 2015, the total number of investee companies in VC and PE portfolios reached 606, which was a 9% increase over the previous year. The number of high-tech companies as a proportion of all VC and PE-backed investees increased slightly from 38% to 39%.  Source: AVCAL

Note: Amount refers to combined total of seed, early stage, balanced VC and later stage VC funds. |

|

Snapshot of Australian VC Industry (as of 30 June 2014)

Source: AVCAL

Number of Investee Companies in Australian VC and PE (as of 30 June 2015)

Source: AVCAL

1. High-tech: A company with exclusive ownership of certain intellectual property rights such as design rights, patents, copyrights, etc. which are critical elements in adding value to the products and business of a company and which are being developed in-house by the company’s permanent staff.

2. Cleantech: Companies or investments focused on products or services aimed at reducing energy consumption, pollution or waste.

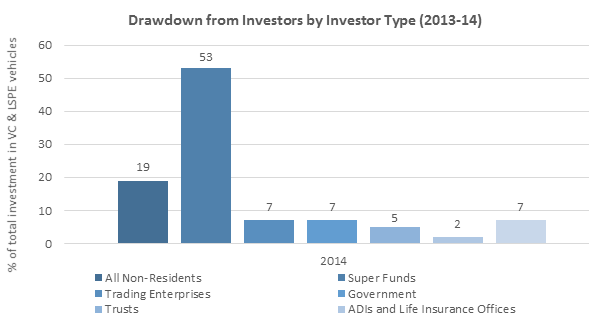

Super Funds the Biggest Contributor to VC Fundraising VC commitments from Australian superannuation funds accounted for 54% of total VC fundraising in 2015, followed by private individuals and corporates. A large proportion of this was attributable to Brandon Capital Partners’ MRCF3 fund, which raised capital from super funds AustralianSuper (AUS), HESTA (AUS), Statewide Super (AUS), and Hostplus (AUS). According to a report by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), there was a total of AUD 18,514 million committed to Venture Capital and Later Stage Private Equity (VC & LSPE) investment vehicles as of 30 June 2014. Of this, super funds were the largest source of funds in terms of drawdowns for VC & LSPE investment vehicles, with a contribution of 53%.  Source: ABS

Note: Percentages have been rounded up.

VC Investments in Australia Concentrated at Early Stage Funding In 2015, the majority of VC investments were in early-stage funding (seed, startup and other early stage), with only 16% of companies invested in at the later VC stage. Close to half of the total VC dollars invested in FY2015 was in early stage rounds (seed and Series A), with Series A rounds accounting for 40%. In terms of the number of investments, seed and Series A rounds made up 71% of the total, with the number dropping sharply for Series B and above, indicating a large gap between early and later stage VC investment. VC Investments in 2015 by Stage of Investee Company

Source: AVCAL

Note: Stages with fewer than three companies receiving investments have been grouped into “Other”. Percentage figures have been rounded off to the nearest whole percent, and refer to the percentage of either total PE or VC investment.

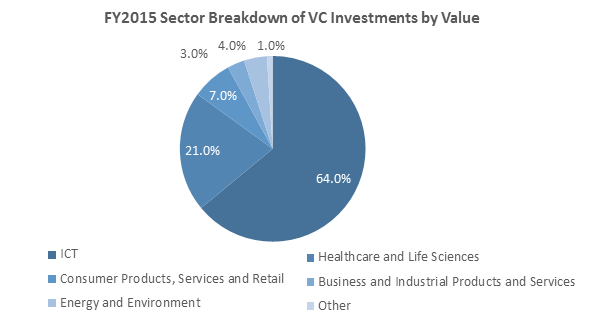

ICT Most Popular Sector for VC Investment, Followed by Healthcare A total of AUD 144 million was invested in the ICT sector in 2015, which made up two thirds of the total investment value for the year. The sector was also significant in terms of the number of startups receiving VC investment— 49 startups in the ICT space received VC investment in 2015, representing over half of the yearly total. Due to a lack of specialist funds, investment in the life sciences/biotech sector witnessed a decrease both in value terms and in terms of the number of life sciences startups receiving VC investment. These fell by 19% to 29 and by 27% to AUD 46 million respectively. The majority of VC investment in life sciences companies in 2015 was comprised of follow-on rounds for existing portfolio companies. In terms of investor source by region, although domestic ICT startups have seen increased interest from international VC firms in recent years, investment in life sciences companies continues to come purely from local VC firms. |

Source: AVCAL

Source: AVCAL

Note: Sectors with fewer than three companies receiving investments have been grouped into “Other”. |

Sydney Biggest Region for VC Activity due to Flourishing Startup EcosystemAccording to data from StartupAUS, there are an estimated 1,200 tech startups in Australia, accounting for 0.06% of all Australian businesses. A 2014 survey found that 48% of Australian startups were in the state of New South Wales (NSW), followed by 18% in Queensland and 13% in Victoria. Sydney, located in the state of NSW, has the biggest tech startup ecosystem in Australia. It is 55% larger than the next biggest, Melbourne (located in the state of Victoria). Over 64% of Australia’s tech startups and up to 15% of Australian workers employed in the ICT sector are located in the Sydney Government Area, since the region hosts a large number of tech/finance/telecommunications companies. Due to the strong concentration of startups in the area, there are also a number of incubators and accelerators such as telecommunications giant Optus’ Innov8 (AUS), ANZ’s InnovyzSTART (AUS), and BlueChilli (AUS). Australian Venture Capital Investment in 2015 by Region

Source: AVCAL

Note: Locations with fewer than three companies receiving investments or for companies whose headquarter location have not been disclosed by the VC or PE firm have been aggregated into “Other”.

Trade Sales Account for Majority of VC Divestments in 2015 In FY2015, the total number of companies exited by PE and VC fell to 51 from 70 in FY2014 and 68 in FY2013. Trade sales accounted for the majority of VC exits. One such exit was the sale of Spinifex Pharmaceuticals, backed by GBS Venture Partners (AUS), Brandon Capital Partners and Uniseed (AUS), to Swiss-based Novartis for an upfront payment of USD 200 million. Meanwhile, non-trade sales for VC included the listing of 3P Learning (AUS), an online education provider backed by Insight Venture Partners (USA), on the ASX in July 2014. VC Divestments by Exit Route in 2015

Source: AVCAL |

|

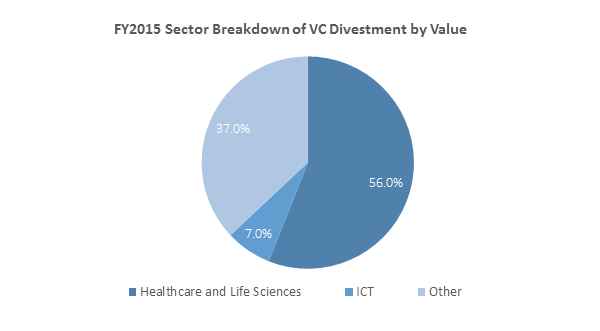

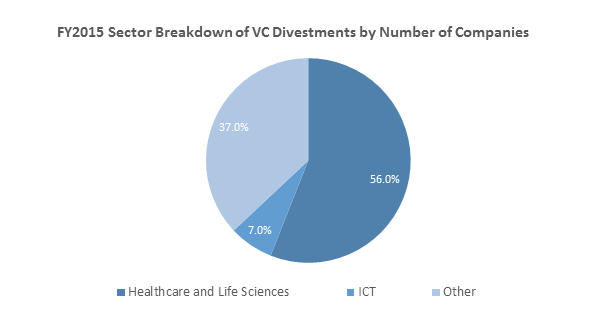

Healthcare and Life Sciences Biggest Contributor in Terms of Amount Divested at Cost The healthcare and life sciences sector was the biggest contributor in terms of amount divested at cost in 2015, contributing a 38% share. This was generally attributed to the listings of Healthscope (AUS), with an IPO issue size of over AUD 2 billion, and Estia Health (AUS), with an IPO of AUD 725 million. Meanwhile, the business and industrial products and services sector contributed a roughly 25% share both in terms of total divested companies and the total amount divested at cost. One significant exit in this sector was the sell-down of Pacific Equity Partners’ (AUS) post-IPO stake in credit reporting agency Veda (AUS), which listed on the ASX in December 2013. |

Source: AVCAL

Note: Sectors with fewer than three companies divested have been grouped into “Other”.

Source: AVCAL

Note: Sectors with fewer than three companies divested have been grouped into “Other”. |

Competitive Trends

|

Several Large-Capital Funds Launched in Recent Years Showing Upswing in VC Industry Due to the recent push toward investment and government support for the innovative sector, the Australian VC industry has seen a number of funds launched in recent years which are notable for their significantly larger pool of capital compared to past years. This increase in committed capital can be attributed to factors such as a rise in investment from offshore investors as well as renewed interest from superannuation funds in the VC industry. In 2014, USA-based Insight Venture Partners made an AUD 266 million investment in Campaign Monitor (AUS), a Sydney-based email marketing campaign developer. This was the largest ever single VC investment in an Australian technology company, reflecting the increased interest from foreign VC investors in recent years. Further, offshore investors accounted for 44% of the announced deal value in FY2015 compared to 36% in FY2014. Likewise, with the opening up of super funds into the VC market, 2015 saw the launch of three AUD 200 million funds backed with investment from a combination of private investors and superannuation players. These were Blackbird Ventures’ second tech fund, backed by super funds First State Super (AUS) and Hostplus Super; Brandon Capital Partners’ Medical Research Commercialisation Fund 3 (MRCF3), backed by super funds AustralianSuper, HESTA, and Statewide Super; and Square Peg Capital’s new venture capital fund, backed by HNWIs such as billionaire James Packer and several super funds (presently undisclosed). There has also been increased government support toward the innovative sector, which has been another contributor to boosting VC investment. For example, in November 2015, government-owned Australia Post (AUS) announced the 2016 launch of its Innovation Capital Fund, which is expected to grow to an eventual AUD 100 million. The fund has a special focus on drone technologies. List of Registered ESVCLPs, AFOFs and VCLPs as of October 2015

Source: by UZABASE |

|

Blackbird Ventures Blackbird Ventures is a tech startup-focused VC firm founded in 2012. The company has 2 major funds; the first was launched in 2012, with a total of AUD 30 million backed by 35 investors, the majority of whom are themselves tech entrepreneurs (including the founders of successful Australian tech startup Atlassian); and the second in 2015, with a total of AUD 200 million, again from tech founders in addition to superannuation funds First State Super and Hostplus. Blackbird typically takes equity stakes of between 5% and 20% in local start-ups. List of Blackbird Ventures’ Investee Companies

Source: CrunchBase |

|

Square Peg Capital Square Peg Capital was founded in 2012 by SEEK (AUS) co-founder Paul Bassatt. The company has a focus on venture and growth stage online and technology companies, with a geographic focus on companies based in Australia and New Zealand, South-East Asia and Israel. In 2015, the company opened an AUD 200 million fund with backing from James Packer and other prominent HNWIs, along with several undisclosed super funds. List of Square Peg Capital’s Investee Companies

Source: CrunchBase |

|

Brandon Capital Partners Brandon Capital Partners was founded in 2007 with a focus in the life sciences space. Brandon Capital manages three funds: Brandon Biosciences Fund 1, established in 2008 with a total of AUD 50 million; the Medical Research Commercialisation Fund (MRCF) Trust 1, established in 2007 with AUD 11.1 million; the MRCF IIF, established in 2011 with AUD 40 million; and the MRCF3 Fund, established in 2015 with AUD 200 million. The MRCF3 is backed by super funds AustralianSuper and Statewide Super, HESTA, and Hostplus. The fund aims to ensure greater commercialisation of Australian medical technology and is Australia’s biggest life sciences fund to date. Around AUD 50 million of the fund will be put into 20-30 early seed stage investments in biotech or medical device startups, with the remaining AUD 150 million set aside for later-stage investments. List of Brandon Capital Partners’ Investee Companies

Source: CrunchBase |

|

Artesian Capital Management Artesian Capital Management (AUS) is an alternative investment management company spun out of ANZ Banking Group’s capital markets business in 2004, with a focus on early stage ventures in Australia and China. The company is backed by ANZ Private Equity and runs a number of smaller funds including Slingshot, Sydney Angels Sidecar Fund, iAccelerate (AUS), BlueChilli and Ilab (AUS). VentureCrowd VentureCrowd was launched in 2013 and has grown to become one of Australia’s most prominent equity crowdfunding platforms. To date, companies have raised more than AUD 10 million using the VentureCrowd platform. Starfish Ventures Starfish Ventures (AUS) was established in 2001 with a focus on high-growth ICT, life sciences, and clean tech companies. The company has raised three funds: the PreSeed Fund and Technology Funds I and II, amounting to a total of over AUD 400 million. The team has invested in over 60 companies with 14 trade sales and IPOs, including listings on the NASDAQ, AIM and ASX. GBS Venture Partners GBS Venture Partners was established in 1996, with a focus on early-stage investing in the healthcare, biotech and life sciences spaces. The company has raised over AUD 400 million across its five funds: The Australian Bioscience Trust, GBS Bioventures II, The Genesis Fund, GBS Bioventures III, and GBS Bioventures IV. The team has invested in a number of successful medtech startups, including Spinifex (clinical stage drug development) and Pharmaxis (AUS) (pharmaceuticals). |