Stalling Investments in Infrastructure and the Expanding Infra Debt Burden in India

|

Apart from targeting rural development, the Finance Ministry’s new budget announcement at the end of February 2016 prioritised the need to upgrade infrastructure and reinvigorate investment in the sector. The finance minister, Arun Jaitley, acknowledged in his budget speech that India had fallen short of its targets for modernising its infrastructure and that many of the projects have been stalled by disputes, red tape and lack of finance. In order to sustain India’s rapid economic growth, the government is dedicated to reviving investments in infrastructure and allocating more funds through various proposals. With the new budget, the government allocated USD 32 billion for infrastructure development in 2016-17, a 22.5% (or USD 5.9 Billion) increase YoY. A year earlier, the 2015 budget, had additional spend of USD 11 billion on infrastructure outlay. However, with a huge infrastructure supply gap the country’s funding requirement is much larger. A CRISIL study stated that India needs INR 6 trillion of investments every year or around INR 17 billion every day from April 2015 to March 2020. In short, India needs INR 31 trillion in investment over the next five years to provide uninterrupted power to homes and factories, and improve roads, telecom, transport and other urban infrastructure. Over each of the last three government’s five-year plans, estimated investments in infrastructure have doubled and a larger share of investments was projected to come from the private sector. One of the main challenges in scaling up private investment was the mobilisation of debt financing for meeting the ambitious targets set by the Government.

Source: Uzabase from various sources

Under the current Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, whose unwavering goal has been to boost economic growth, the daunting task has been to attract private sector capital to improve roads, rail, ports, power and other infrastructure. The government is now opting to use public money to kick-start investments in the sector, as many projects have been stalled by a lack of private funding. This year’s budget included USD 11 billion in increased commitments through Private Sector Enterprises for infrastructure investment. More involvement by the private sector through investments and project operations has become a reality through models like Public-Private Participation (PPP), which not only allows the private sector to raise capital but also improve the efficiency of projects. Given the fiscal constraints that exist, there has always been pressure on public investments at the scale required, PPP has emerged as the principal vehicle for attracting private investment in infrastructure, and India has attracted a lot of PPP investments over the years. A large portion of theses PPP projects rely on private capital that has to be raised from domestic financial institutions. The challenge in India and in a lot of other developing countries is that they do not have the capacity or instruments to provide long-tenure debt for projects having a long payback period. Since PPP projects have been usually financed on a 30:70 ratio of equity and debt, mobilisation of the requisite debt resources has become a mounting challenge, and many infrastructure project promoters are now submerged under huge loans that have turned non-performing. To pay off at least a portion of their bad debt these large project developers are desperately selling their cash-generating assets, crippling cash flows and financial capacity. On the other hand, banks and financial institutions (FIs) are seeing their books turn bad, and cannot lend any further to these borrowers. The big dilemma facing the government, banks and corporates in recent years is raising resources for many stalled infrastructure projects. According to the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE), the number of stalled projects touched an all-time high of 893 ventures worth INR 11.36 trillion at the end of 2015-16, which are held up due to the lack of promoter interest, unfavourable market conditions and lack of funds. Over the last few years especially, stressed assets have been detrimental to the infrastructure sector. This is a grave concern, as non-recovery of loans from the sector has affected ongoing projects and projects hitting completion. Worst of all it has impeded investment in Greenfield projects. |

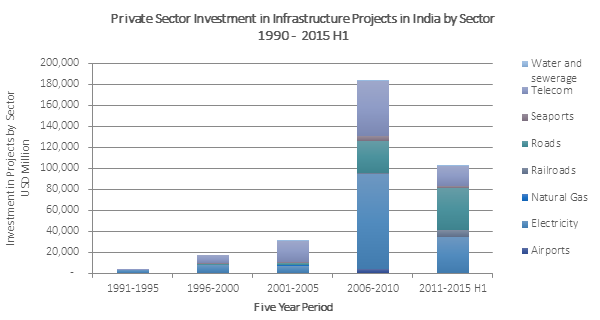

Plummeting Private Sector Investments in Indian InfrastructurePrivate sector participation in infrastructure investment reached a 10-year low in 2015 as the country fell out of the top five countries globally, for private sector investments in infrastructure. But this has been in line with the global trends as private participation in infrastructure (PPI) in the emerging markets of Brazil, India, and China saw declining investments. These countries have been traditionally the large players in PPI, however investments tumbled in China, India, and most notably Brazil, where the combined commitments dwindled to just USD 1.8 billion in H1 2015 from USD 30.9 billion in H1 2014.  Source: World Bank, PPI Project Database

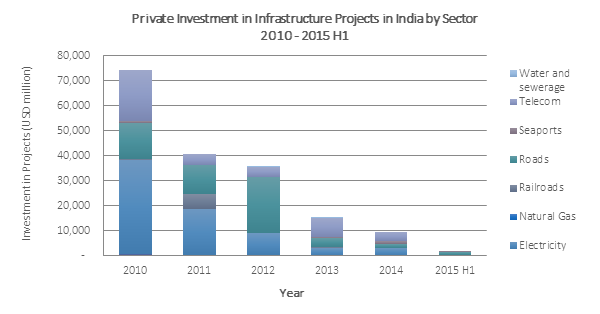

Private investment in infrastructure in India had increased rapidly from 2006, and peaked in 2010, but ever since it has been on a rapid decline. The World Bank predicted in 2013 that the slowdown would continue in the longer term due to rising domestic concerns, especially with financing.  Source: World Bank, PPI Project Database

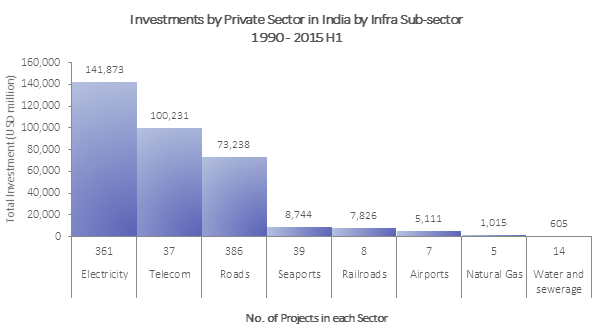

The largest investments have been traditionally in electricity, telecoms and roads. However investments in the telecom and power sector have declined significantly in the last five years. Though sector specific decline was expected in transport and energy, there have been larger, looming reasons for the decline. The biggest challenge has been that public banks, which have been the main source for infrastructure financing, have been overstretched and are reaching their exposure limits. Moreover there has been an absence of a domestic corporate debt market (which is only 2% of GDP) and a lack of foreign equity and credit (equity FDI is only 1.2% of GDP) in India’s private infrastructure market to relieve this exposure. The current infrastructure-financing gap is estimated to be USD 750 billion of the targeted USD 1 trillion spending on roads, ports, power and other infrastructure for the current five-year plan (2012 – 2017). The USD 750 billion is essentially 75% of the required funding that would need to come through debt, much higher than what the government had in mind initially when planned. This figure is also five times the existing INR 9.2 trillion (USD 144 billion) of bank loans that have been disbursed to Indian infrastructure projects to date. |

Government to Kickstart Infrastructure Finance and Remove Regulatory HurdlesA year earlier, the 2015 budget proposed the creation of a ‘National Investment in Infrastructure Fund’ with an initial annual allocation of USD 3.25 billion. The NIIF is structured like a fund of funds, where it will invest in more sector specific funds or at different phases of funding, based on investor appetite. The fund, which is still being set up, is expected to invest in public sector infrastructure finance companies. The companies in turn will be able to leverage their higher credit rating to access domestic and international debt markets, including foreign pension and insurance funds and institutional investors. The government has budgeted to contribute INR 200 billion to the fund in the current fiscal year (2016-2017) while another INR 200 billion will be raised through sovereign wealth funds. It will, however, be interesting to see whether the NIIF will complement or invest directly in other infrastructure investment special purpose vehicles (SPVs) that already finance infrastructure projects, such as the Infrastructure Development Finance Company (IDFC) and Indian Infrastructure Finance Company Limited (IIFCL). To mobilize additional finances for infrastructure spending the government proposed that it will permit infrastructure regulatory agencies, including the National Highway Authority of India (NHAI), Power Finance Corporation (PFC), Rural Electrification Company (REC), Indian Renewable Energy Development Agency (IREDA), National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD) and Inland Water Authority to raise bonds up to the extent of INR 313 billion in the current year. The government’s fresh allocation of USD 2.25 billion to roads and USD 1.6 billion to railways in the current fiscal year is also expected to improve liquidity in the system by encouraging public sector led investments in infrastructure, through EPC, Cash Contract and Annuity models for the awarding of projects in these sectors. The government has also sought to improve the regulatory setup and reboot the PPP framework by improving the PPP dispute resolution process. The new budget put forward recommends a ‘Public Contracts (Resolution of Disputes) Bill’ and a ‘Regulatory Reform Bill’ that would aim to ensure greater consistency across the country’s various regulators and regulations. With bad loans and stressed assets on the rise, the government also sought to improve the investment environment, by pushing for the recapitalization of Public Sector Banks (PSBs). Under project Indradhanush, the government had proposed that it will infuse INR 250 billion into public sector banks in each of fiscal years 2016 and 2017, and INR 100 billion each in fiscal years 2018 and 2019. These proposed amounts are still short of the estimated INR 2.3 trillion of capital that Indian public sector banks need by 2019. Most of the support is expected to come through government capital infusions as banks still find it difficult to raise capital from the equity capital markets. This year’s budget also sought to improve the last-mile connectivity in many infrastructure sub-sectors, including power, railways and ports. The budget included provisions to help electrify the last remaining 20,000 villages that are still not connected to the grid by 2020. The last-mile connectivity plans for ports and railways propose to link the 12 major ports to the rail network to move cargo, which is expected to increase efficiency and reduce cost, when compared with road transport. |

Investments in Power and Roads Continue to DominateThe top three sectors in terms of investments through PPI have been in electricity, telecoms and roads, but over the last 5 years investment has been mainly in roads/highways and electricity. Until 2010, the largest investments went into the telecoms sector, but more recently electricity and highway projects have garnered more investment.  Source: World Bank, PPI Project Database

Road and highway projects though large in number are still small based on project costs, when compared to telecoms and electricity. Over the last 25 years, the largest 10 projects in India with PPI investments are listed in the following table. Private Participation in Infrastructure in India – Top Projects 1990 – 2015 H1

Source: World Bank, PPI Project Database

The government’s allocation to roads in the 2016 budget through the road transport and highways ministry now stands significantly higher at INR 579.76 billion (up 23.1% from INR 471.07 billion in FY16). Overall, the budgetary allocation towards the key transport segments – roads and railways – stands at INR 2.18 trillion, and if the allocation towards the upgrade of state highways is included, the figure expands further to INR 2.21 trillion. These investments will dramatically improve transit timing and are expected to reduce the per km cost of transportation. For the current fiscal year, the government plans to build 10,000 km of national highways and upgrade another 50,000 km. It is slowly making progress in terms of efficiency in road construction, building 13 km of roads a day, which is still less than half the speed at which the government aimed to build (30 km/day). The railways are also seeing a major push in the proposed investment plan of INR 1.21 trillion for 2016-17, with the government providing budgetary support of INR 43.01 billion. This is about 43% higher than the proposed investment plan for fiscal 2015-16. The plan will also invest in developing railside logistics parks that will allow terminals and sheds to handle container traffic to create an integrated transport system with ports. These investments will dramatically improve efficiency in logistics by reducing transit timing and the per km cost of transportation. The railway logistics and freight container trains proposed to run on time-tables, will give new options for logistics managers to lower costs and improve timeliness. The Renewable Energy sector has globally attracted a lot of private equity investment in recent years, and it has fared well in India too. The sector is expected to expand from 32 GW to 175 GW by 2022. Against this backdrop, the government has allocated an outlay of more than INR 100 billion for 2016-17. This outlay includes INR 50 billion from the National Clean Energy Fund (NCEF) with the balance coming from Internal & Extra Budgetary Resource (IEBR). Moreover, India is emerging as a key destination for renewable energy projects, as the government has provided incentives to infrastructure and programs designed to attract investment. India topped the ranks in 2015 with USD 11.8bn of announced FDI in the sector, which included Lightsource Renewable Energy’s plans to invest USD 3 billion, to design, install and manage more than 3 GW of solar power within the country. |

The Real Concerns in Sustaining Infrastructure Investment and the High Financial Leverage of Infrastructure CompaniesWhile the public sector in India had opted out of infrastructure development spending to free up fiscal resources since the early 1990s, more has been left to the private sector and bank financing. Most often infrastructure lending was done by commercial banks that lent on a large scale to private sector infrastructure companies, and over time this has presented another set of challenges. Not only are the private sector companies involved in infrastructure development now excessively reliant on bank financing, they do not have any other options for raising capital, as they cannot tap corporate bond markets or other long term funds such as insurance and pension funds. With bank credit being the principal source of debt funding for infrastructure projects, credit is only available for a maximum tenure of 10-15 years, which does not match the typical 20-30 year tenure of an infrastructure concession contract. The issue is exacerbated when considering infrastructure project loans have tenures of 10 to 15 years, bank deposits, the main source of funds; typically have a maturity of less than 3 years. With the rapid growth in lending to the infrastructure sector between 2000 and 2010 there has been a growing risk of an asset-liability mismatch (ALM). The Reserve Bank of India (RBI – India’s central bank and banking supervisor) and banks have become cautious on the issue related to financing infrastructure loans. Several domestic public and private sector banks have neared their group exposure limits set by the RBI for lending to large infrastructure players. Over the last few years, the banking supervisor has expressed serious concerns about the level of non-performing assets of the banking system, especially due to the loans provided to the infrastructure sector. As these loans have had a disproportionate share in the aggregate non-performing assets, banks are reluctant to increase their exposure. This has taken toll on many of the infrastructure firms, which are unable to complete their current projects without cleaning up their balance sheets. With this situation it is expected that private infrastructure investment is going to stall for a few more years, with new investments in Greenfield projects to be most negatively affected. There is now a growing onus on the public sector to revive infrastructure investments. In real terms the consolidated debt of over 250 companies in the steel, construction, infrastructure development, power generation and distribution sectors rose by around 10% in 2014-15 from the previous year. Power generation and distribution have been the most indebted sub-sectors, with the consolidated debt of these companies rising to INR 4,730 billion in 2014-15 from INR 4,263 billion in 2013-14. India is already known to have one of the world’s highest levels of electricity transmission and distribution (T&D) losses, due to technical inefficiency and theft. Apart from that many of India’s utilities also lose significant electricity-related revenue because of poor collection efficiency, and retailers are forced by their state governments to sell electricity at subsidized rates, which now accounts for INR 600 billion (USD 9.1 billion) every year as costs exceed tariffs. With such large amounts of debt, private sector investments have virtually ground to a halt, and the difficulties that these companies face reflect the problems that the Indian financial system is grappling with. Where the cost of capital has been high, banks are reluctant to extend credit because they have too many bad loans. The RBI has conditionally allowed banks to roll over loans to indebted infrastructure companies, only if they have good assets. So until these indebted groups can raise the cash to repay the banks, either by selling assets or completing projects to generate the required cash flow, new investments are not going to meet the scale of funds required for the country to upgrade its infrastructure assets and meet the growing demand. A Credit Suisse report titled “House of Debt”, which was first released in 2012 and then updated in 2015, has outlined the financial stress and indebtedness that ten large Indian corporate groups went through. Most of the corporate groups are in the infrastructure space, and their indebtedness has intensified over the last 3 years. These companies included the following groups: Lanco Group, Jaypee Group, GMR Group, Videocon Group, GVK Group, Essar Group, Adani Group, Reliance Group, JSW Group and Vedanta Group. All the three major ratios of debt servicing of these groups have suffered deterioration: interest cover, debt-to-earnings and debt-to-equity. Their overall debt has risen to INR 7,335 billion from INR 6,532 billion between 2012-13 and 2014-15. With many of the projects stranded due to insufficient financing, the companies have been caught up in high financial leverage, and debt repayment. Over the past eight years, the corporate debt of these 10 over-leveraged corporate groups covered by the Credit Suisse list grew by an alarming seven times. Declinining Debt Servicing Ability of Groups Operating in the Infrastructure Space in India

Source: Credit Suisse

*Essar P&L numbers are for FY14, debt is based on data available for FY15, with remaining figures assumed to be the same as in FY14

These figures also take into account the fact that these companies, despite resorting to asset sales in order to deleverage their balance sheets, have seen their stress levels rise. This is evident by looking at how debt has eaten into the equity of these companies, especially those operating in infrastructure and power projects, which were initially built at a debt-to-equity ratio of 70:30, as that ratio has now shifted to 90:10. For example the market cap-to-debt ratio in the case of GVK Group is 95:5. In any case, the corporate debt ratio in India, which is only a moderate 50% of GDP, has been highly concentrated, with the top 1% of firms accounting for about half of the debt, as do corporates in the infrastructure (including power, telecommunications and roads) and metals sectors (including iron and steel). Ever since the global financial crisis, the median debt-to-equity ratio of these corporations have been at more than 175%, not only higher than corporates in other sectors in the country, but also among the highest among corporates across emerging economies. BMI Research expects Indian banks to continue to report a significant amount of bad debt, this is not surprising as the financial position of the country’s infrastructure conglomerates continues to deteriorate. With no signs of improvement, the RBI has been vigorous in promoting regulation and norms regarding restructuring loan repayments and refinancing, and in cleaning up the banking system. While the RBI has been in the balancing act of safeguarding banks from the mounting NPAs and restructured loans, the government has been keen on easing non-performing asset norms for bank loans to revive projects. |

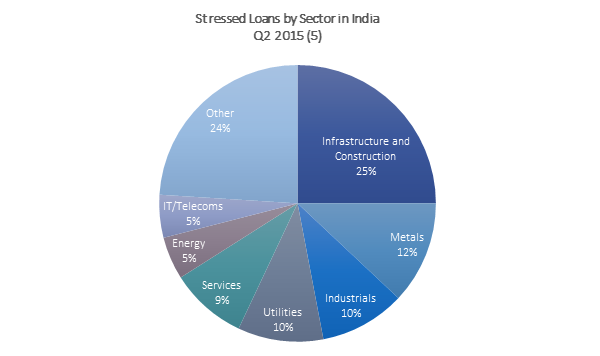

Public Sector Banks (PSBs) most Exposed to Stressed Loans in the Infrastructure SectorThough India has been able to sustain itself as an emerging market ‘bright spot’, there has been growing apprehension about its banking system which has been weighed down by bad loans and the growing level of stressed or restructured loans. Over time, the public-sector banks (PSBs) have taken the largest share in lending to large-scale infrastructure projects. The main issue has been with the long gestation periods of these projects, making recoveries very difficult. The Economic Survey for 2014-15 held that infrastructure, iron & steel, textiles, mining (including coal) and aviation, held 54 per cent of total stressed advances of PSBs as on June 2014. The survey noted that the exposure of PSBs to infrastructure stood at 17.5 per cent of their gross advances and was significantly higher than private sector and foreign banks. Gross NPAs of Banks in India Mar-2010 – Mar-2015

Source: Department of Banking Supervision, RBI

The RBI also conducted sectoral credit stress tests for the infrastructure sector and the largest sub-sectors that included power, transport and telecommunications. The infrastructure sector as a whole has been assessed as highly stressed, with its share of NPAs standing at 12.7% and standard restructured assets at 46%. Among the sub-sectors, the power sector was the most stressed with a share of 29.3% in restructured assets and 5% in total NPAs. In contrast, the transport sectors share of restructured assets was 14.6% and 3.8% of NPAs, while for the telecom sector these figures were 1.8% and 1.7% respectively.  Source: Credit Suisse

The stressed loans of Indian banks were to the tune of 14 % of gross advances (USD 161 billion) as of March 2015. Reviewing the trend of growth in the number of stressed loans, over 30 per cent were from the Infrastructure sector – primarily in the power space. A large proportion of these loans were to government-controlled power generation and distribution companies. Operating inefficiencies (technical and commercial), lack of adequate availability of cheaper domestic coal and inability to pass on the increased costs to consumers have impacted these companies adversely. |

|

The Regulators Scramble to Plug the System through Opportunities for Refinancing Over the next four years, New Delhi says the state banks will need about USD 28bn in new capital. Of that, the government for its part has already provided a USD 11 billion bailout to struggling PSBs, while also promising structural reforms. With the RBI not completely receptive to the idea of setting up a special purpose infrastructure fund or a development financial institution which would lend to projects that require last-mile funding, these assets end up being classified as stressed assets. As aside from NPAs, banks also carry loans that were restructured — where borrowers have sought more lenient terms such as reduced interest rates or extended repayment period, in order to make payments and allow banks to classify the loans as standard assets. But while the RBI closed the restructuring window for banks in April 2015, listing various measures taken to provide impetus to infrastructure lending and address the stress in the sector, the RBI and Finance Ministry are allowing banks and FIs to enter into a take-out financing arrangement with IDFC and other Financial Institutions (FIs) under the 5:25 scheme. Banks are now allowed to have flexible structuring and refinancing of project loans under the 5:25 scheme, and banks can issue long-term bonds with a minimum maturity period of seven years with certain incentives. The central bank has recommended that the lenders should take advantage of the 5:25 scheme, a provision that allows banks to refinance loans for infrastructure for up to 25 years, and the strategic debt-restructuring scheme, which allows debt-for-equity swaps. Essentially banks now have the right to convert their loans into a majority equity stake if they feel that a change in ownership can help turnaround the borrower’s business. Under the 5:25 scheme, banks can fix longer repayment schedules, even for say 25 years, for loans to infrastructure projects. Additionally, the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) has recently relaxed the norms on debt – equity conversion by banks in stressed listed entities. This could enable the banks to get a controlling equity stake in such companies so as to enforce a change in the management, and eventually improve efficiency. The flexible loan restructuring scheme stipulates that loans given to infrastructure and core industries in which the aggregate exposure of all institutional lenders exceeds INR 5 billion, the debt can now be repaid over a maximum of 25 years and the banks will refinance the loan every five years. The repayment at the end of each refinancing period would be structured as a bullet repayment, being specifically mentioned upfront that the loan will be refinanced and that it would be considered in the asset liability management (ALM) of banks. According to some recent estimates the loan amount already refinanced under this scheme is on the order of INR 1 trillion. The RBI is also allowing the creation of infrastructure debt funds as Non-banking financial corporations (NBFCs) or mutual funds. However, while capital infusion and restructuring might provide short-term relief, it is clearly not a sustainable answer to a complex problem. The argument against the 5:25 scheme is that it is largely being used as just another tool to postpone the write-offs, even though they admit that the scheme is a better way of restructuring loans compared with corporate debt restructuring (CDR). Though the 5:25 guidelines allows banks to increase the tenure of the loans so that they can match each project’s inflows and outflows, the issue is whether these loans eventually default. Taking for example the power sector with its INR 750 billion worth of loans, even if these debts are put under the 5:25 scheme, not all of them will eventually turn positive. Given that about 35-40% of the restructured accounts have eventually defaulted, there may be a large percentage of debt being shifted to the 5:25 scheme that will eventually end up in default. In terms of dealing with the stressed loans, banks have preferred to address the problem through restructuring debt under the Corporate Debt Restructuring (CDR) mechanism. While recovery of assets has mainly been the responsibility of banks, they are not well equipped to manage recoveries and so there is the dire need to promote agencies that can manage distressed funds such as Asset Reconstruction Companies (ARCs). A two-pronged strategy that needs to be implemented has been Asset Reconstruction and Asset Disposal. Currently, the banking industry has resorted to the former, which is the sale of the distressed assets of the bank to an Asset Reconstruction Company (ARC), thereby disposing of the debt. After the sale, bad loans become the responsibility of the ARCs and relieve banks from the pressure of recovering loans, while also generating capital. According to media reports, the Finance Ministry is working towards creating a public-funded ARC, which will help in the bailout. Along with reconstruction, currently a ‘Bankruptcy Code’ is also being worked out, as this is expected to go a long way towards helping local lenders to better manage their non-performing and stressed assets. The real challenge in the current environment has been the RBIs call for banks to clean up their account books by early 2017, the central bank has implicitly implied that it would be closely scrutinizing whether concessions made to the lenders are being misused. The RBI governor, Raghuram Rajan, stressed the importance of such a clean-up in his speech on 11 February 2016, where he reiterated that the profitability of some banks may be impaired in the short run, but that once the system was cleaned up, it will be able to support economic growth in a sustainable and profitable way. With the RBI intent on getting banks to clean up their loan books, the likely credit costs which were supposed to be spread over the next three to four years will have a much higher incidence in FY16/FY17. |

|

Infrastructure Investments Unlikely to Make Headway in the Short-Term The main issues for infrastructure projects in India have been their commercial viability and long gestation periods, but more recently the focus has shifted to stalling private investments in the sector due to growing indebtedness and the high financial leverage of firms operating in the infrastructure space. Lending to infrastructure companies has pushed up the NPLs and stressed loans in the banking sector, as these companies completely rely on banks for lending, due to the absence of a deep corporate bond market in India and muted participation by pension funds that have inhibited credit availability for long-term financing. While the 10-15 year tenure of lending is too long for banks, it is too short from the point of view of project companies, resulting in an asset-liability mismatch issue. Further regulations such as sector specific resolution of stressed assets, implementation of a strong bankruptcy code and institutionalising a formal mechanism to revive sick companies are needed to resolve stressed loans. Above all, a credible, timely and realistic mindset is required to ensure sustained recovery management. The quick action in enacting a modern bankruptcy law, will also allow infrastructure projects that have turned into bad loans to be speedily handed over to new promoters capable of attracting fresh financing. The Finance Ministry, in a mid-term review of the economy last year, had acknowledged the concerns springing from over-leveraged private balance sheets and the need for higher public investments to compensate for India Inc’s inability to take up Greenfield projects. But even after a year, investments by the public sector have yet to see an improvement. Hopefully with more funds committed to the road sector, where the award of projects both under EPC (engineering-procurement-construction) and a new ‘hybrid annuity’ model may make headway, more can be done to support the power and railway sector. Though in the short run (3-5 years) the private sector involvement in the infrastructure investment space is going to be constrained, with reviving demand and continued economic growth, continued reforms in cleaning up the banking system and a public sector push in infrastructure spending, the sector is likely to see growth in the medium to long term. |