Country Report 2017 Sri Lanka: The Dollar Hungry Nation

Executive Summary

|

Continues to be a Lower-Middle Income Economy With Expectations to Reach Upper-Middle Income Status Within the Next Two Years Immediately after the end of its 26-year civil war, Sri Lanka enjoyed substantial improvement in its economic growth accompanied by high infrastructure development (8.5% during 2010-12). At this rate, the country was expected to reach upper middle income status by 2014, at the latest. However, a sudden slowdown in growth in 2013 and beyond (average of 4.4%), has kept the nation from its aim of reaching the GNI per capita of USD 4,035. The current growth of the national economy is upheld by rapid growth in consumption while its external trade position is held in check by tourism receipts. Meanwhile, the country’s long-held foreign revenue stream via expat remittances has become a rising concern due to the political and economic crisis in the Middle East. In addition, lack of sufficient capital formation and the persistent rupee depreciation are identified as underlying reasons for slow growth. However, at this rate of growth, we expect Sri Lanka to be an upper middle income economy by 2019E. The report details on the underlying dynamics of the decelerating economic growth of Sri Lanka and the broad macroeconomic environment. An Ageing Population with No Demographic Dividend Poses a Challenge The United Nations (UN) predicts that Sri Lanka could see decelerating population growth caused by declining fertility rates in the country when compared to peer countries in the region. This changing dynamic of the population story, together with the increasing life expectancy in the country, will have a dramatic impact on the labour force and healthcare, and in turn the overall economy, by restraining the country’s demographic dividend. Moreover, the ageing population will also lead to a high dependency ratio which will strain the budgets of families as well as the government. |

|

Debt Burden Advances as Currency Continues to Depreciate The Country’s weak balance of payments has led to a persistent LKR depreciation against the USD to reach LKR 152.3 as of end-April 2017 from LKR 132.9 two years ago. As a result of the worsening import bill, the sterilised exchange rate intervention adopted by the Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL) has led to Sri Lanka’s external debt growing. As per our point of view, sterilising the exchange rate interventions was an error, given the present context of the macroeconomic environment which has excess liquidity. This led to high inflationary pressure built in the country. |

|

Money-Led Inflation Unresponsive to Monetary Policy? With the sterilising of exchange rate interventions on the one side and further increase of money supply to settle debts on the other, Sri Lanka has increased its money supply by 27.1% YoY in 2016. The accompanying policy rate cut has boosted credit in the system, and added to inflationary pressure in the economy. Even though the CBSL is currently settled on a tight monetary policy with the aim of reversing this trend, inflation has been unresponsive (headline inflation at 8.6% as of March 2017). As we see it, Sri Lanka is in need of a major change to its monetary framework which addresses the context of the overall macro environment as opposed to the current framework which merely targets the money supply. The strategies adopted for economic recovery must not be done in isolation with only one specific aim such as currency stability, but rather, need to address the multiple elements of the macroeconomic imbalance. |

|

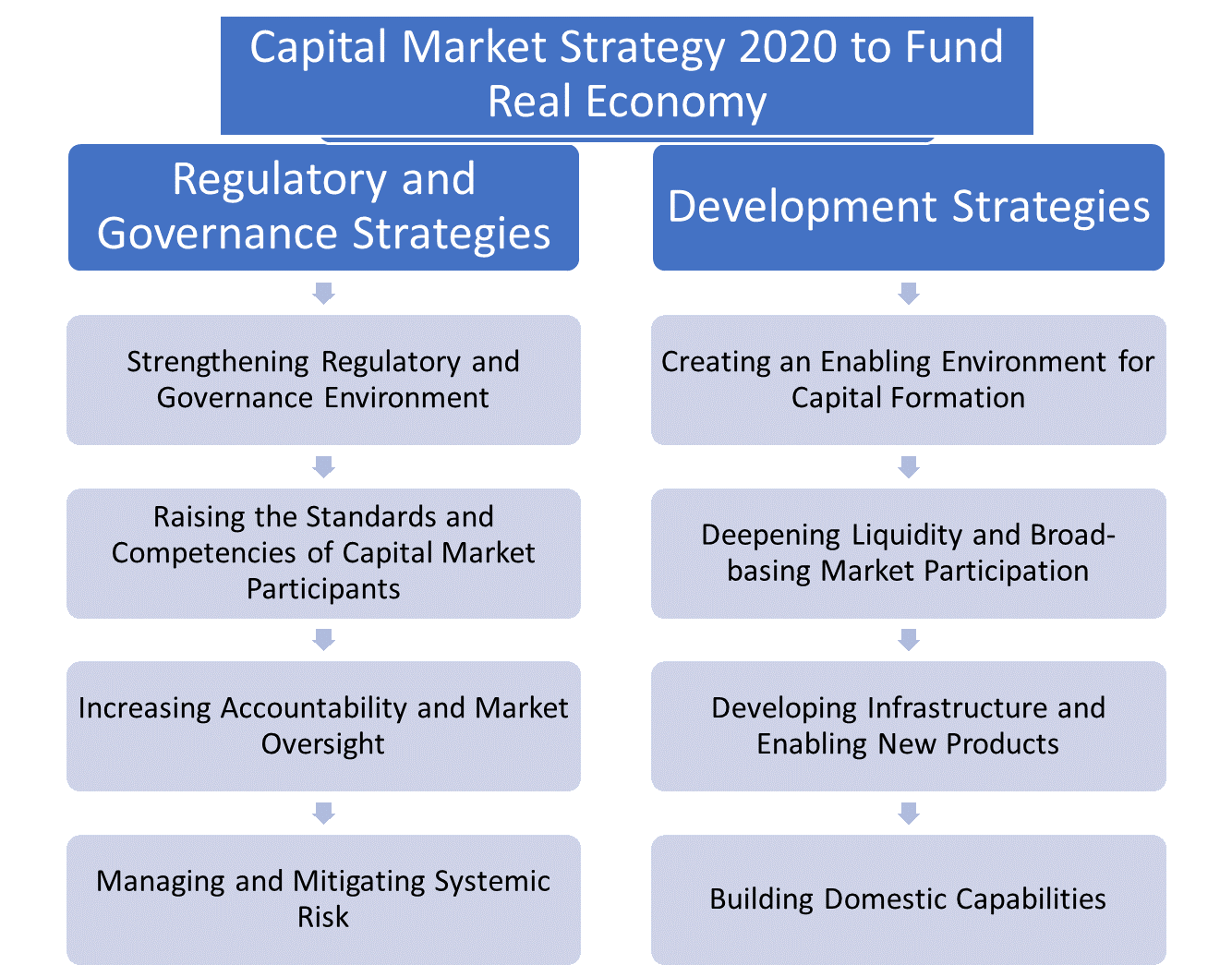

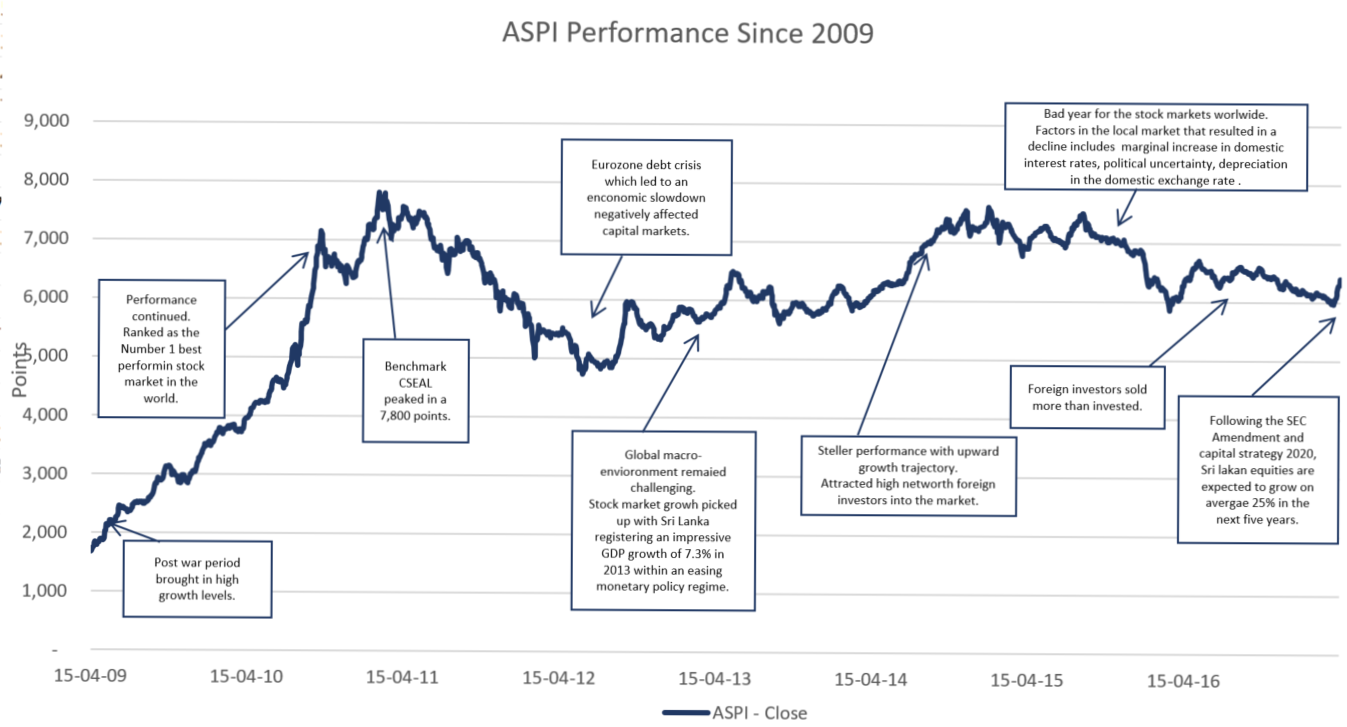

The SEC Act to Revamp the Nascent Capital Market The Sri Lankan capital market, as a less developed frontier market characterised by low market participation, is recovering after periods of instability. The stock market which experienced a boom during the post-war period, fell back as regulation was unable to keep up with the surge in activity. However, with the new government in power, the Securities Exchange Commission (SEC) has put forward a roadmap focused on updating the SEC Act in which the exchange and the regulator are being revamped, making it easy to attract and deploy the capital Sri Lanka needs. This is expected to include key initiatives such as strengthening regulatory environment, raising standards of capital market participants, increasing accountability and market oversight, together with development strategies such as broad basing market participation and developing infrastructure and enabling new products. |

Country Overview

|

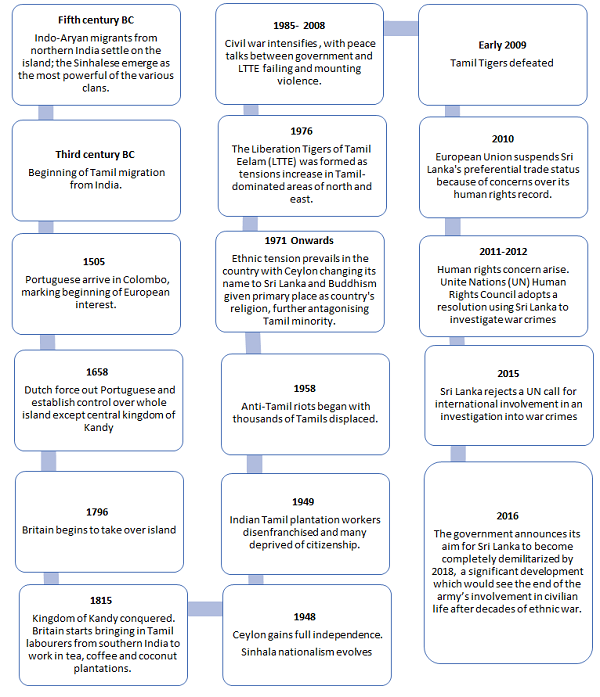

Former British Colony Thrives Post Civil War Situated on the southern tip of the Indian subcontinent, the ‘resplendent island’ shares a history of over 2,500 years with diplomatic ties and trade with other countries. Ancient Sri Lanka, which was ruled by kings with a self-sufficient village-based economic system was colonised by the British since 1796 and remained so until independence, in 1948. Towards the latter part of the 19th century, agriculture became the dominant sector in the country with production and export of tea, rubber and cinnamon gaining prominence. However, during the country’s post-independence period, the government in Sri Lanka pursued policies of industrialisation with the aim of diversifying an economy that was solely based on crop exports, while improving the standard of living in the country. Today, Sri Lanka has transitioned from a predominantly rural agricultural economy (2015: 7.9% of GDP, 1950: 41.0%) towards a more urbanised economy driven by services (2015: 56.6% of GDP). Further, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) rate Sri Lanka as one of the best among developing countries on the Human Development Index (HDI). However, an important and devastating period post-independence was the decades-long civil war and conflict that prevailed in the country. The primary place given to Buddhism as the country’s religion provoked the Tamil minority which led to the formation of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) and increasing tensions in the Tamil-dominated north and east. This civil war intensified affecting tourism, agriculture and fisheries. Since the end of the civil war in May 2009, the economy achieved high rates of growth (average annual economic growth rate in 2010-12 at 8.5% vs 5.0% in 2000-09). Furthermore, the new administration, elected in 2015, has pledged its commitment to inclusive governance and economic reform, as well as rebalancing its foreign policy and reconciling with the country’s ethnic minorities. Such peace and stability signal a new beginning for Sri Lanka, supporting the country adjust its development model as it aims to become a higher middle-income country. Going forward, economic growth will likely require continued structural changes towards greater diversification and productivity increases. |

|

Key events that formed Sri Lanka’s history

Source: UZABASE, BBC

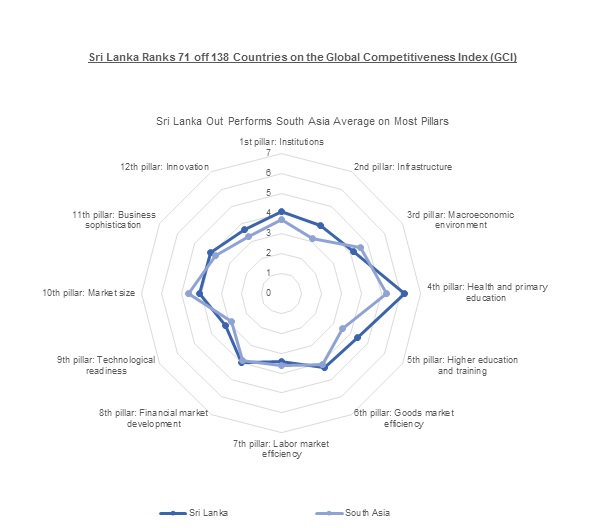

Source: The Global Competitiveness Report 2016-2017 |

|

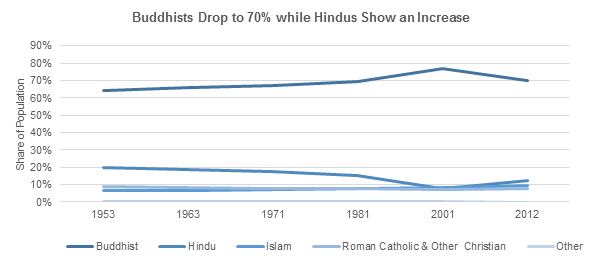

Religion and Ethnicity in Sri Lanka: A Context of Diversity The key religions practised in Sri-Lanka are Theravada Buddhism, Hinduism, Christianity and Islam. As per the religious census for 2012, 70.1% Sri Lankans were Buddhists practising the ‘Theravada Buddhism’ followed by Hindus (12.6%), Islam (9.7%) and Roman Catholic (7.6%). The country is blessed by the teachings of these four main religions. Compared against the last census carried out in 2001, the number of followers for Buddhism dropped to 70.1% in 2012 from 76.7% in 2001, while the number of Hindus have shown an upward trend rising to 12.6% in 2012 from 7.8% in 2001. However, Buddhism has continued to dominate the religious landscape. |

Source: Department of Census and Statistics

Note: Jaffna, Mannar, Vavuniya, Mullaitivu, Kilinochchi, Batticaloa and Trincomalee districts in which the 2001 census enumeration was not completed are not included here. |

|

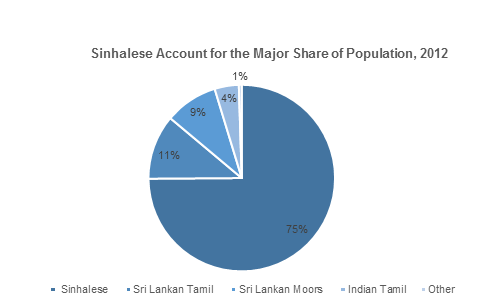

The country which shares a group of religious beliefs and practices saw the rise of ethno-nationalism with ethnic groups being more interested in protecting their own interests than building a national identity. The ethnic groups of Sri Lanka comprise of the Sinhalese who accounted for the majority share of the country’s population (74.9%) followed by the Sri Lankan Tamils (11.2%), Sri Lankan Moors (9.2%), Indian Tamil 4.2% and other (0.5%) (2012 estimates), with Sinhala being the official and national language spoken by 74% of the total population followed by Tamil (national language 18%) and other (8%). Despite Sinhala being the official national language, English is spoken competently by about 10% of the population, and is referred to as the link language in the constitution. The ethno-religious differences in the country during the 1970s unfortunately gave rise to mutual mistrust and dragged the country into a devastating 26-year civil war. Although the Sri Lankan Civil War, which originated with Sinhala being the official language, was not fought along linguistic lines. The difference in ethnic groups was the driving force for the war with the formation of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), better known as the Tamil Tigers. The end of the war did not resolve the ethnic problem, but with the present administration that was elected in 2015 attempts are being made to resolve the problem. |

Source: Indexmundi |

|

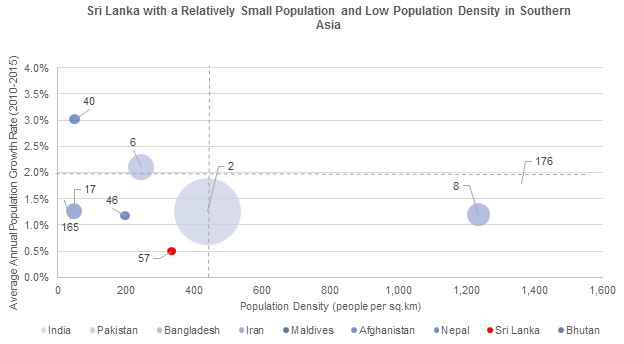

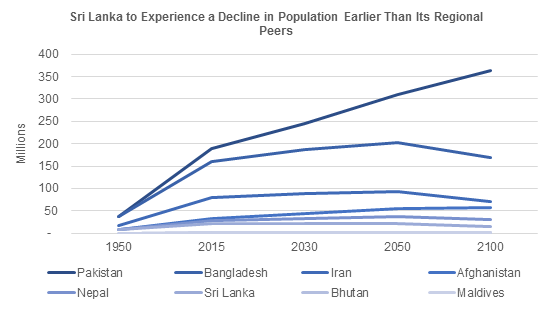

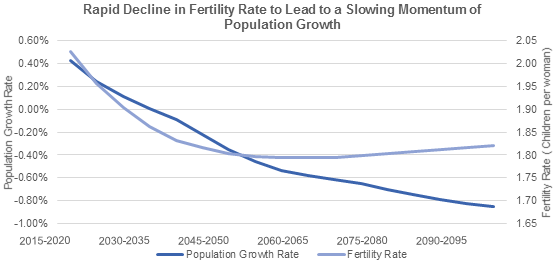

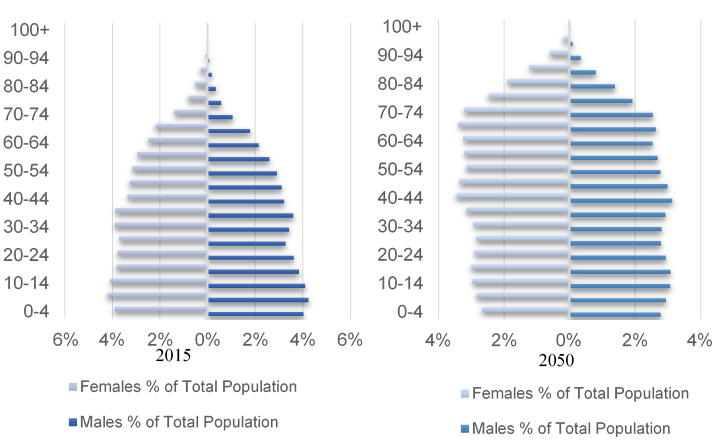

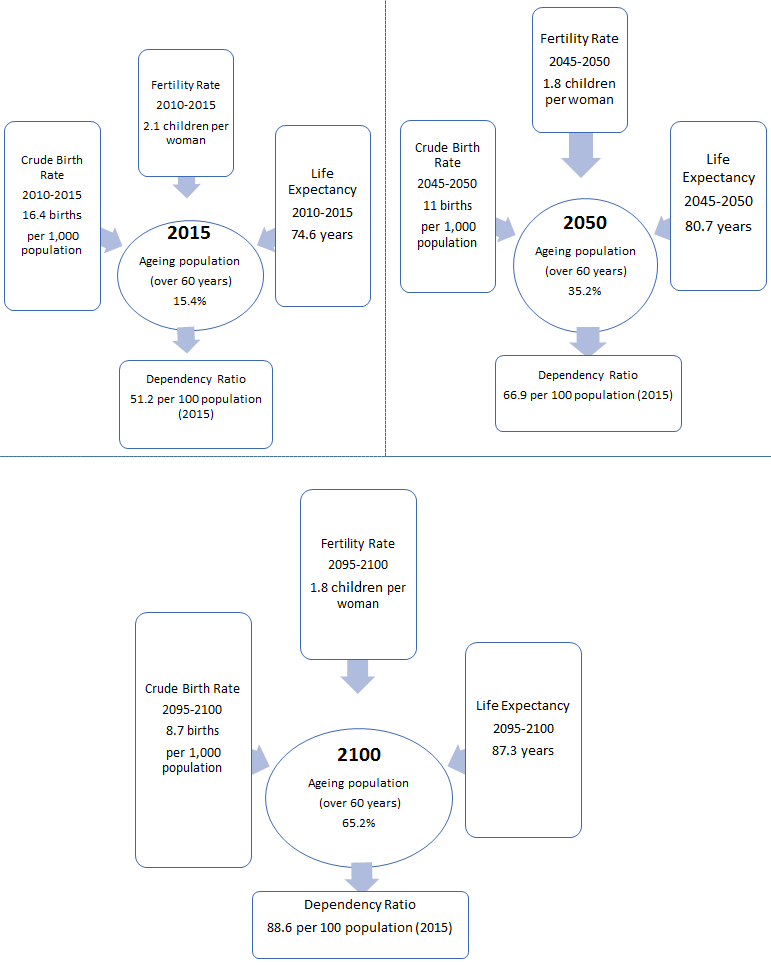

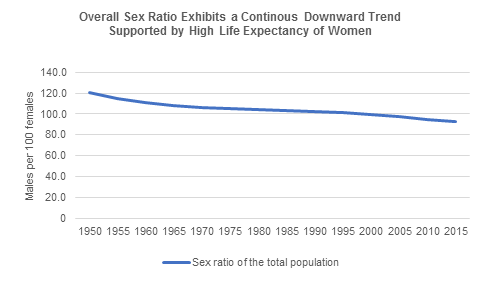

Sri Lanka to Experience a Contracting and Ageing Population with No Demographic Dividend As of 2015, Sri Lanka was the 7th most populated country in South Asia with a population of 21 million (lower than the South Asian median of 32.5 million, but almost 4 times larger than the world median of 5.4 million). During 2010-15, Sri Lanka grew at an average annual population growth of 0.5%, the lowest level of growth in South Asia (1.4%). Population density was at a moderate level of 334.3 people per sq.km (Square Kilometre) as of 2015, ranking 4th off the 9 South Asian countries and 32nd worldwide ( higher than the population density of Asia: 137.39 people per sq.km). Furthermore, the United Nations (UN) predicts Sri Lanka to continue to have a population in the range of 20-21 million till 2030, and experience a decline afterwards, while most peers will experience a decline only after 2050. This phenomenon is explained by the rapid decelerating population growth supported by the declining fertility rates in the country when compared peer countries in the region. The UN further states that by 2100, Sri Lanka will have a fertility rate (1.82 children per woman) lower than that in certain developed countries such as the USA (1.93 children per woman). Sri Lanka is likely to experience an ageing population driven by this changing dynamic of the population story together with the increasing life expectancy in the country. Sri Lankans are living longer, helped by investments in human development such as health and education, resulting in an increasing proportion of Sri Lankans living to reach a life expectancy of 87.3 years by 2095-2100. On present trends (2010-2015), life expectancy at birth in Sri Lanka (74.6 years) is higher than the current average in Southern Asia (67.7 years). However, a critical aspect of life expectancy trends in Sri Lanka is that male adult life expectancy has stagnated since the 1970s, even whilst female life expectancy has rapidly increased. The population projections assume that in future male life expectancy will keep pace with improvements in female life expectancy, else the ageing population will be predominantly female. Moreover, the ageing population in the country together with these phenomena will have dramatic impacts on the labour force and health, as well as the economy by restraining the country’s demographic dividend. Unless labour force (2015: 53.8% of the Sri Lankan population above the age of 15) and employment rates (2015: 95.3% of the labour force) including women increase (2015 estimates: female labour force participation rate: 35.9%), the country will have a high dependency ratio which will strain the budgets of families and the government as well. |

Source: World Bank, UZABASENote: Size of the bubble represents population, while the label indicates the rank worldwide.The lines indicate the average across the South Asian Countries

Source: World Bank- Population

Source: World Bank

Sri Lanka to Witness an Increase in Ageing Population by 2050

Source: United Nations, UZABASE

Ageing Population – a Universal Phenomenon, Looms Particularly Large for Sri Lanka

Source: UZABASE

Source: World Bank |

|

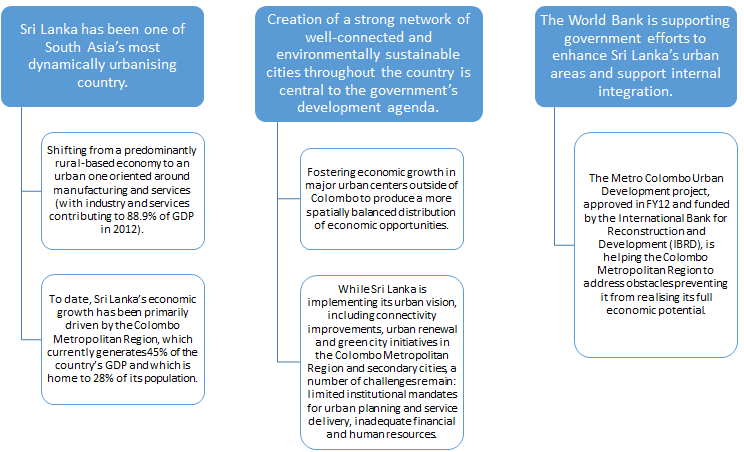

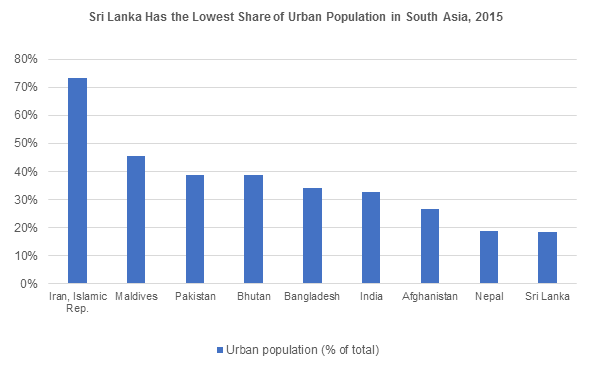

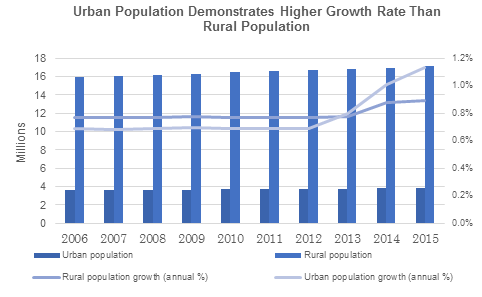

Messy and Hidden Urbanisation Takes the Form of Ribbon Development Along Major Transport Arteries As of 2015, Sri Lanka recorded the lowest share of urban population at 18.4% (3.8 million) when compared to other countries in the South Asian region. For Sri Lanka, official estimates indicate that the share of the population living in towns and cities fell slightly between 2000 and 2010. However, the urban population of Sri Lanka over the past few decades has reached 48% of the total population of the country in real terms, in contrast to the official statistics. Based on the agglomeration index, total urban population in Sri Lanka was 35.3% in 2012, in contrast to the official statistics figure of 18.3%, indicating the existence of hidden urbanisation in Sri Lanka similar to those in other South Asian countries such as Bangladesh, India, Maldives and Pakistan. Sri Lanka has a visibly high rate of urbanisation and ambitious plans for further urbanisation through the envisioned Western Region Megapolis Project. As per World Bank, Sri Lanka has performed better than other countries in the region, with urbanisation being less “messy” where only a relatively small portion of the urban population living in slums, largely eradicating extreme urban poverty. Furthermore, Sri Lanka was the country in the region with the fastest expansion of urban area, as measured using night-time lights data, relative to urban population. Sri Lanka’s “messy” urbanisation is reflected in patterns of sprawl and ribbon development especially in the Colombo metropolitan region and along with other major transport arteries. This differs from majority of South Asian countries where messy urbanisation is associated with large slum populations and a high incidence of extreme urban poverty. The share of Sri Lanka’s urban population living below the national poverty line was among the lowest in the region at only 5%, as opposed to 14% in India, 13 % in Pakistan, 21% in Bangladesh and 15% in Nepal. Thus, given the rapid expansion of urban area through ribbon development relative to urban population and the government’s aim to achieve its Urban Vision framework by 2020 will assist the country in the rural-urban transition. |

|

Sri Lanka to Witness Rural-Urban Transition Supported by its Urban Vision and Assistance from International Bodies such as World Bank

Source: UZABASE, World Bank

Source: World Bank, UZABASE

Source: World Bank, UZABASE |

|

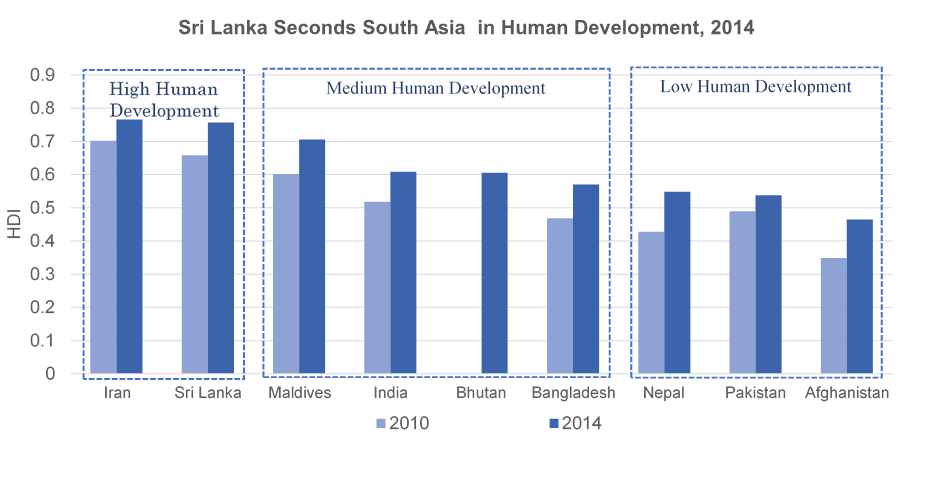

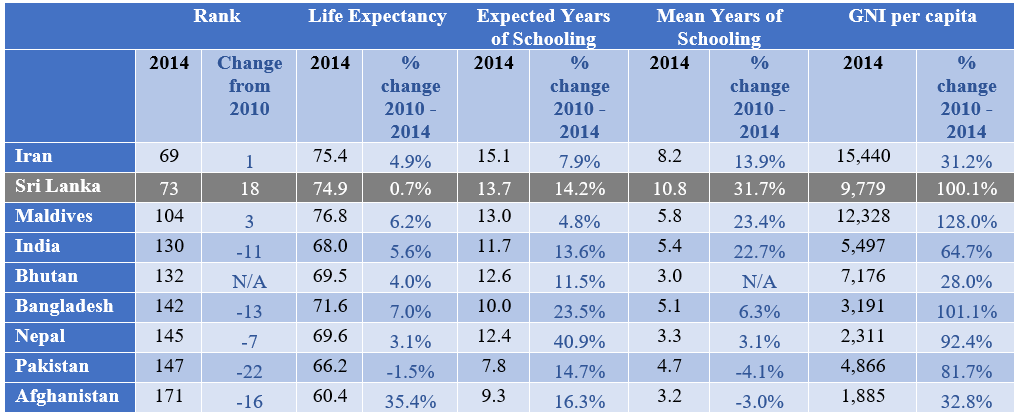

Sri Lanka Seconds South Asia in HDI, Maintaining its Position in the High Human Development Category Sri Lanka has remained in the high development category moving a notch from 74th place in 2013 to 73rd place in 2014 out of 188 countries, per the Human Development Index (HDI). The HDI is measured based on health, education, standard of living and gender equality by the human development report annually. The HDI stood at 0.757 in 2014, higher than the world average of 0.711 and South Asia averaged of 0.607, demonstrating an increase of 11.5% against a value of 0.679 in 2000. Resultantly, Sri Lanka ranks second in South Asia being in the ‘high development countries’ category trailing after Iran (69th), while leading its nearest neighbour, India (130th) in the ‘medium development countries’ category along with Bhutan (132), Maldives (104) and Bangladesh (142). |

Source:Human Development Report 2015Note: Bhutan was not eligible for human development ranking during 2010

HDI Component Indices of South Asian Countries for 2014; Sri Lanka Performs Well over 2010-2014

Source: Human Development Report 2015 and 2010, UZABASENote- GNI (gross national income) is based on 2011 dollar purchasing power parity (PPP). |

|

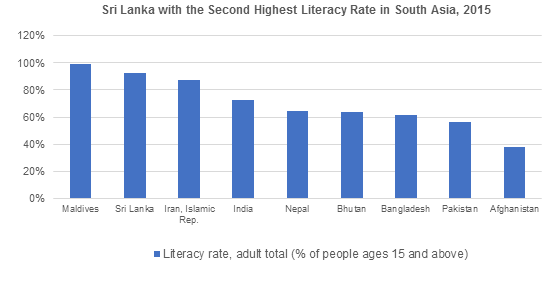

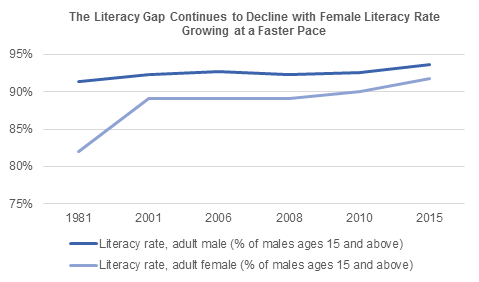

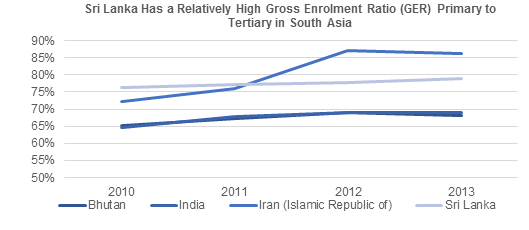

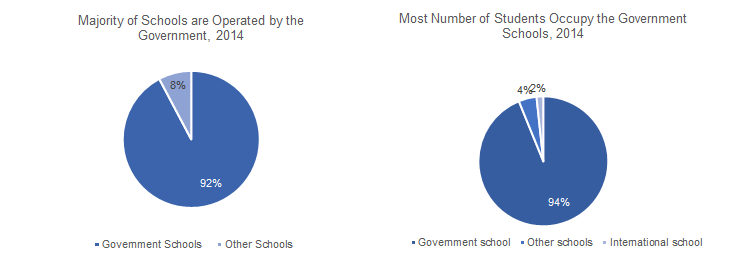

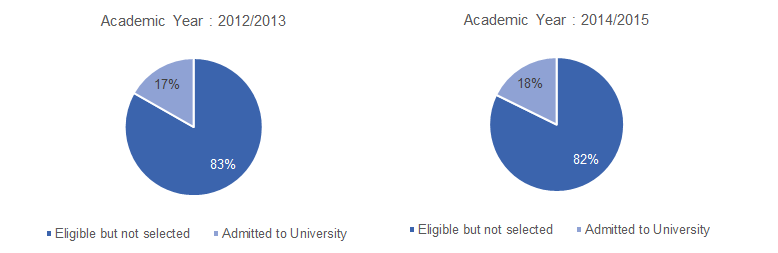

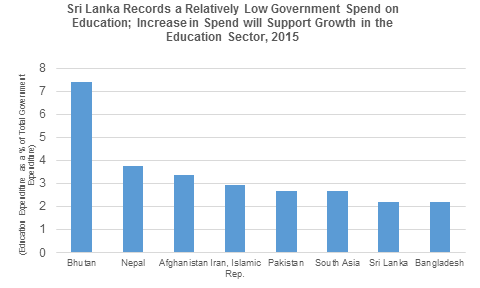

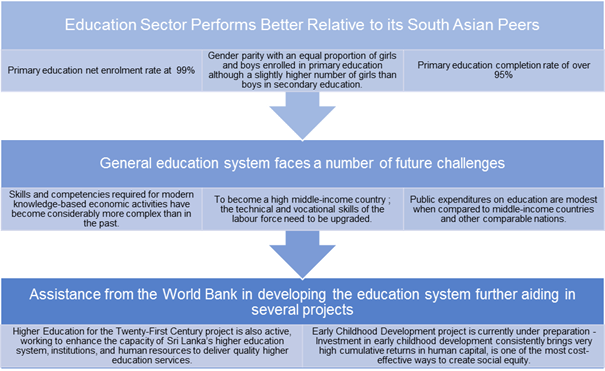

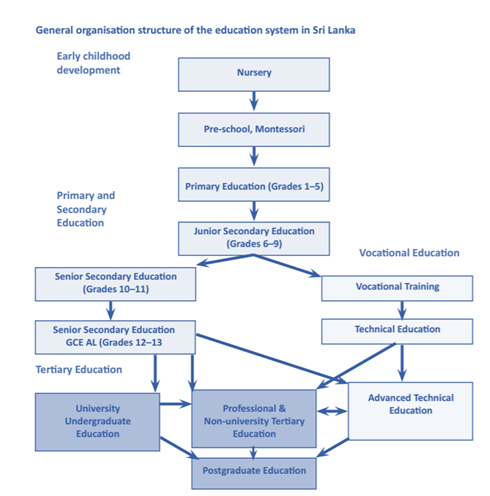

Sri Lanka Aims to be a Knowledge Hub Given its High Literacy Rate in South Asia Literacy is a fundamental human right that is necessary for poverty and broadening participation in society. Sri Lanka’s achievements in education have been impressive, given the second highest literacy rate at 92.0% in South Asia with improvements in the universal access and participation in primary education, high enrolment in secondary education, and gender parity in general education. On a district-wise analysis, it was noted that the rural sector is at a worst situation compared to the urban sector. The highest level of literacy was recorded in Gampaha (98.5%) and the lowest in Batticaloa (89.5%) (UNFPA, 2015). On further analysis, male literacy rate for 2015 stood at 93.6% while female literacy rate was recorded slightly lower at 91.7%. In spite of this, female literacy rate in Sri Lanka has grown at a faster pace, reducing the gender literacy gap during 2010-2015. This was attributed strongly with the Government of Sri Lanka recognising the importance of providing equal opportunities for individuals with difficulties in accessing education and advocating a policy of ‘inclusive education’. Education in Sri Lanka has been playing a pivotal role in the life and culture of the country since 543 BC. Moreover, the role of higher education is a major driver of economic development in Sri Lanka which critically impacts the country’s human capital. With the country advancing as a fast-growing middle-income country, it is critical that a higher education system which can produce skilled, hardworking and enterprising graduates are developed. As of 2015, the state university sector comprised 15 universities, 7 post graduate institutes and 13 other degree granting universities/ institutes. The capacity of the state university system which is limited, is unable to accommodate more than 20% of the 140,000 students who qualify for university education (approximately 8,300 students per state university). Thus, given the importance of human capital, Sri Lanka has targeted achievement of excellence in higher education by 2020 to become the most preferred country for higher education in the Asian subcontinent. The government’s objective of making Sri Lanka a “Knowledge Hub” will make it a key destination for investments in higher education and position the nation as a centre of excellence and regional hub for learning and innovation. The government has already commenced the formulation of necessary legislation to regulate private sector higher education institutes, while the state university system performs as the main provider of the university systems. It is estimated by the government that the establishment of private universities will be attracting approximately 50,000 foreign students to Sri Lanka through proposed investments in private universities while absorbing on average the 12,000 Sri Lankan students leaving the country for higher education, and thereby protecting foreign exchange savings and earnings. Moreover, the bilingual education system that has been in practice since 2009 in Sri Lanka enhances the overall education system, where the students are given a mixture of the mother tongue (Sinhala or Tamil) and English during their schooling years. English language education in Sri Lanka starts from grade one unlike countries such as Japan, Indonesia, Vietnam and Iran where it starts after grade six. This further helps students in their higher studies where English language proficiency is normally a prerequisite. This in turn increases the overall quality of the future labour force and the education system as a whole. Despite the role of English language in the education system in Sri Lanka, the country stills ranks low on English proficiency according to the Education First English Proficiency Index (EF EPI) with a score of 46.58 below the Asian average score of 55.94. The index which measures the average level of English language skills amongst those adults who took the EF test, ranks Sri Lanka 58 out of the 70 countries in the list. |

Source: World Bank

Source: World Bank

Source: UNESCO

Note: Stats for the particular years were not available for the other South Asian countries.

Government Sector Dominates the Education Landscape

Source: Ministry of Education (MOE)- 2016 Report

Marginal Improvement in Capacity in State Universities

Source: University Grants Commission (UGC)

Source: World Bank

Education Sector in Sri Lanka: Challenges and Aims

Source: World Bank, UZABASE

Source: Ministry of Education (MOE) Sri Lanka |

Economic Overview

|

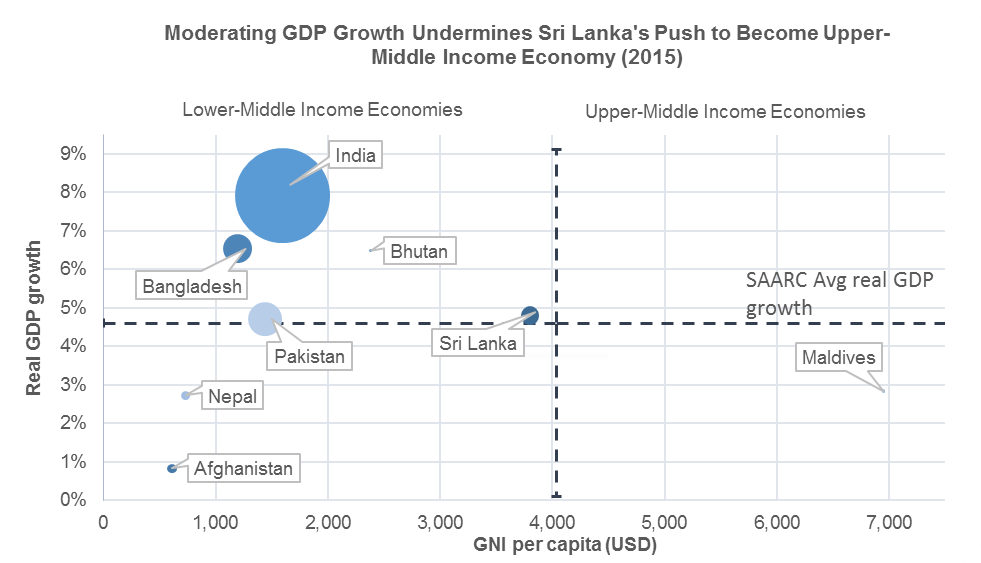

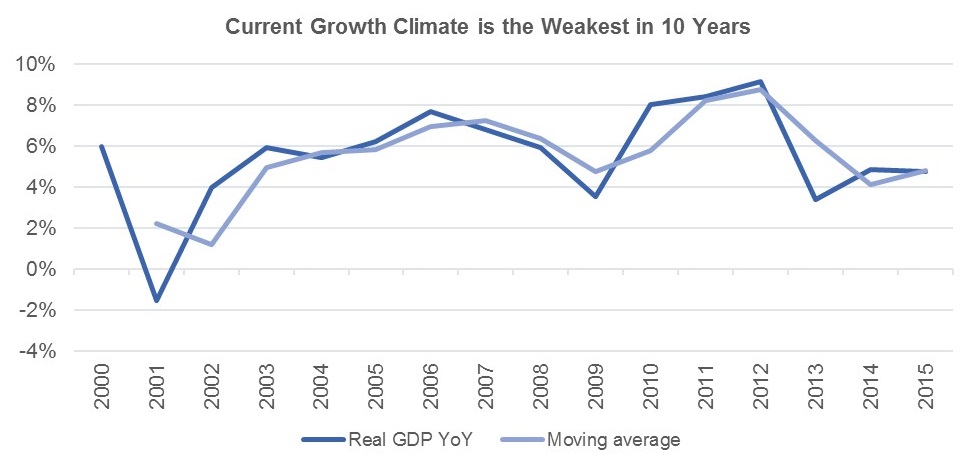

Sri Lanka Retains Low Middle Income Status Due to Declining Economic Growth Sri Lanka, an economy worth USD 82.3 billion in 2015, is the most developed lower middle income economy in the SAARC region with a Gross National Income (GNI) per capita of USD 3,800. Immediately after the end of the 26-year civil war the Sri Lankan economy enjoyed steep growth during the period 2010-12, where GDP grew on an average of 8.5%. The highest growth rate Sri Lanka ever achieved was recorded in 2012 at 9.1%. However, from 2013 this momentum failed to withstand, as the heavy debt employed to finance the civil war expenditure and the substantial infrastructure developments post war, began to imbalance the macroeconomic environment. In a nutshell, the current macroeconomic crisis attributes to the persistent currency depreciation wielding pressure on the forex reserves; accelerating inflation being unresponsive to monetary policy; and the fiscal consolidation. Together these have amplified the burden of debt on the Sri Lankan GDP growth, where growth dipped to 4.8% in 2015. |

Source: World Bank, UZABASE

Note: Bubble size represents the GDP value (USD)

Horizontal dotted line- Average real GDP growth rate of SAARC countries

Verticle dotted line- Cut out GNI per capita (Atlas method) between lower and upper middle income economies defined by World Bank for 2017

Source: World Bank, UZABASE

Note- The chart represents growth of real GDP |

|

As per our analysis, had the economy continued the post war growth persistently, at an average GNI per capita growth of 18.5%, by 2014 the country would have achieved its upper middle income status. Thus, the current economic environment is a crucial constrain on the development of the nation. |

|

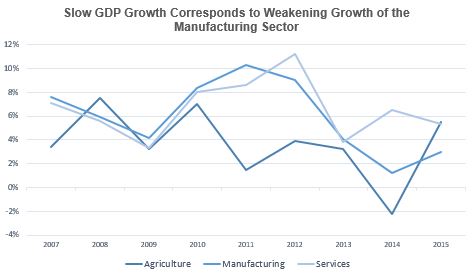

Sri Lanka: A Consumption Driven Economy Supported by the Service Sector Prior to exploring the current macroeconomic concerns, an analysis of the structural composition of the GDP in 2015 insights that Sri Lanka is a service driven economy despite its lower middle income status. Services composed 56.6% of the GDP followed by manufacturing (26.2%) and agriculture (7.9%). The declining economic growth is the result of the weakening manufacturing sector. Over 2010-12 the sector recorded an average growth of 9.2% while over 2013-15 the growth was at 2.8%. This relates to the appreciating rupee which made intermediate goods used in the industrial sector costly, even to the extent of negating the positives of the fall in global oil prices (a key intermediate good imported). However, the declined growth of the service sector also led to the weakening GDP growth, where the sector’s growth was at an average of 5.2% over 2013-15 against 9.2% over 2010-12. Nonetheless, the agricultural sector boomed in 2015 recording a growth of 5.5% YoY compared to the negative rate of 2.2% YoY in 2014. The focus of the new Maithripala government on agriculture along with foreign support is the tailwind of the agricultural boom. The food production national programme 2016-18 is set with the aim of alleviating poverty by ensuring food security, minimising imports and maximising incomes of farmers. Thus far, the government has handed over agricultural machinery and financial grants to farmers. In addition, the EU has also offered aid worth EUR 30 million to modernise the agriculture sector of the country and an extra EUR 12 million for the reconciliation process of good governance and development sought by the new government. However, 2016 saw a weakening of the momentum in agriculture growth due to prolonged dry weather which impacted the value add from rubber, tea, rice and fishing. Thus, from our point of view, the government’s aim to alleviate poverty and the various budgetary steps taken are in alignment and bode well for the growth of the agriculture sector. Despite this, the ability of the government to attract the participation of millennials and the upcoming generations is a challenge, given their lower regard for agriculture, especially farming and fishing. |

Source: World Bank, UZABASE

Note- The chart represents growth of sector GDP |

|

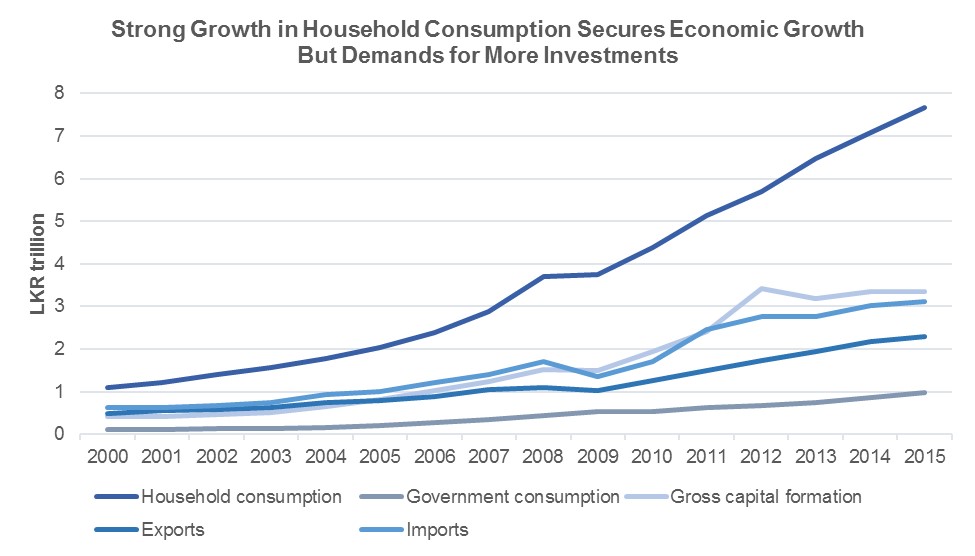

From an expenditure point of view, Sri Lanka is a consumption driven economy with household consumption forming 44.0% of GDP in 2015, while its external sector is import driven. Household consumption has grown at a CAGR of 9.3% over 2009-15, attributed to growth in the purchasing power of consumers (GNI in purchasing power parity terms) at a CAGR of 7.9% during 2009-10. On the one hand, while this trend secured positive GDP growth, excessive growth of household consumption reflects weak capital formation in the country. Both domestic and foreign investments to the country have remained stagnant since 2013. |

Source: United Nations Statistics Division |

|

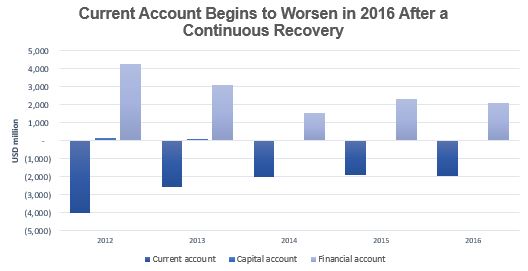

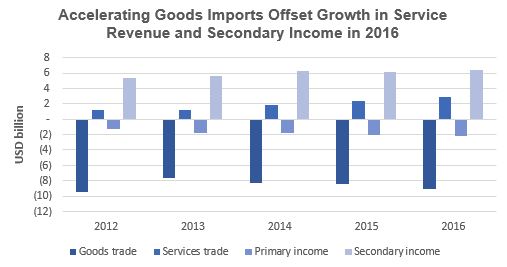

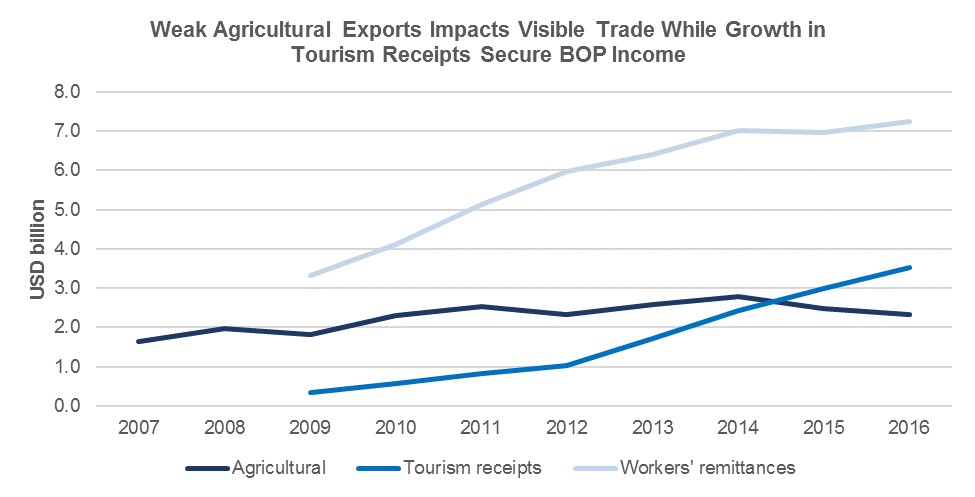

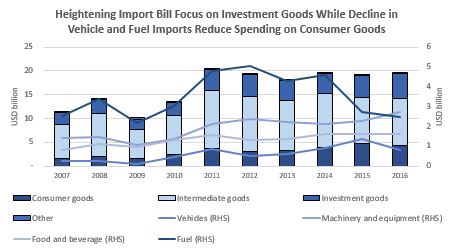

Continued Balance of Payment Deficit Mainly Financed Via Foreign Investments At the forefront of the current macroeconomic crisis is the continuously depreciating LKR against the USD, attributed to the deteriorating balance of payments (BOP). This is primarily due to the continued deficit of the current account, which led to a substantial outflow of the rupee. However, over the period of 2012-15, the current account balance improved attributed to a continued strong growth in tourism at a CAGR of 68.1% during the same period. In addition to tourism receipts, Sri Lanka’s external position was secured by the expatriate revenue sent by Sri Lankans working in the Middle Eastern region. The political and economic crisis in the region has been a significant impact on the expat earnings of the country. In 2016, expat remittances grew only by 3.7% YoY against 9.5% YoY in 2014. A further attribute to the current BOP deficit is the unstable agriculture export revenue which declined at a CARC of 8.8% and the 13.4% CAGR growth in machinery and equipment imports over 2014-16. The decline in agriculture earnings relates to increased consumption domestically given the recorded sector growth, except in 2014, which was subject to a dip in production due to bad weather conditions. The growth of machinery and equipment imports is the result of high government emphasis to boost the industrial sector. Despite government change, every government has brought in budgetary revisions (in terms of tax cuts and exemptions) to facilitate more imports of machinery and equipment and bring in novel technologies being used internationally. These reasons counterbalanced the positive impact of low oil prices and reduced vehicle imports. During the same period import bill of fuel declined at a CARC of 26.5%. Further, the government initiatives taken to reduce imports of vehicles in 2016 were effective as the vehicle import bill fell by a substantial 41.5% YoY. But despite, the current account deficit started to worsen in 2016 by 3.2% YoY. With regard to the worsening visible balance, we are of the view that it should be short-lived, given the initiatives taken by the government to boost the agriculture sector. Moreover, the growth in investment goods (machinery and equipment imports) is not a significant concern. In a period of GDP slowdown, flow of capital goods to the country is necessary. On the other hand, the decline in imports of consumer goods by 8.4% YoY in 2016, amid the depreciating rupee, allows consumption driven GDP growth to reduce its import dependence.  Source: Central Bank of Sri Lanka

Note: Statistics are according to BPM6 revisions applied from 2012 onwards

Source: Central Bank of Sri Lanka

Note: Statistics are according to BPM6 revisions applied from 2012 onwards.

Source: Central Bank of Sri Lanka

Source: Central Bank of Sri Lanka

Note- Consumer goods include food and beverages, vehicles, pharmaceuticals and, clothing and accessories and etcNote- Intermediate goods include petroleum products, textile articles, chemicals and etc

Note- Investment goods include machinery, building materials, transport equipment and etc

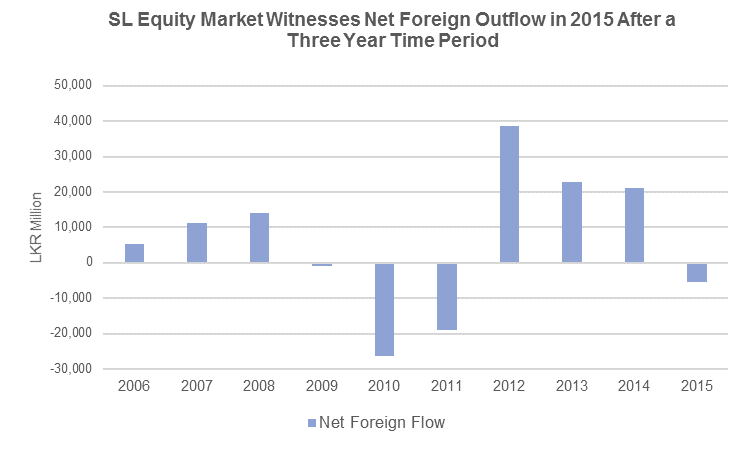

The current account deficit was mainly financed through an improvement in portfolio investments and foreign direct investments which grew at a CAGR of 17.3% and 6.8% respectively over 2012-16. Moreover, general government loans have grown at a CAGR of 6.7% during the same period and on average accounted for 35% of the financial account. However, the repayment of foreign loans, mainly to the IMF has been the next major driver causing outflow of the rupee (after the current account). Over the period of 2013-16, more than USD 1.8 billion has been repaid to the IMF. |

|

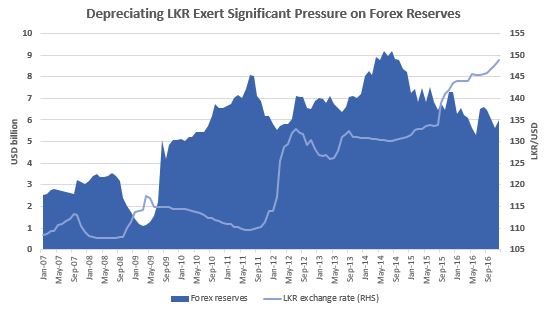

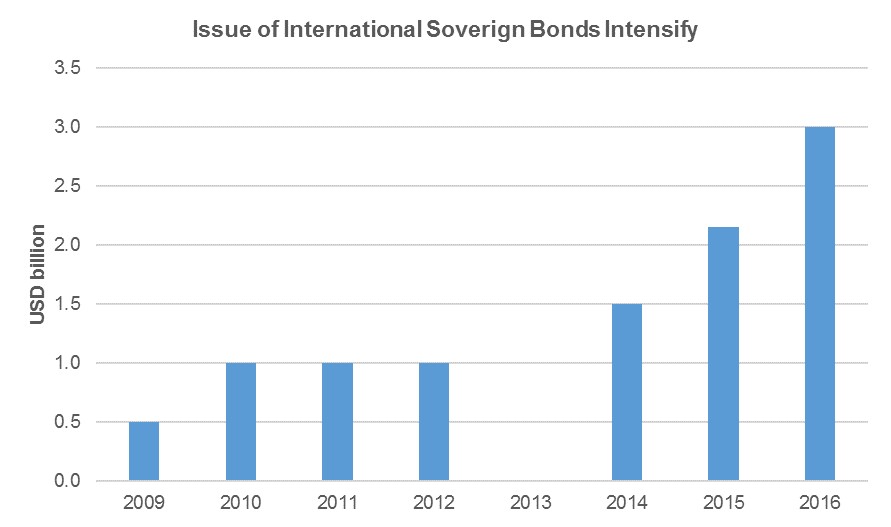

The Depreciating Rupee Places an Unending Burden on Forex Reserves The heavy outflow of currency from the country over the past few years has led to a persistent depreciation of the LKR against the USD, with the exchange rate reaching 151.4 LKR/USD as of March 2017 compared to 132.9 LKR/USD two years ago. Instead of favouring exports, the depreciation caused the import-oriented external trade to worsen. Therefore, on this end, the balance of payments and the LKR exchange rate is tied to a cog, with the rupee in a prolonged state of depreciation. Ultimately the consequences is that the currency is being supported through the depletion of international exchange reserves. Due to inadequate inflow of USD (mainly due to low capital flows), the availability of foreign exchange was insufficient to handle the gravity of the rupee slump. Thus, in September 2015, the CBSL settled on floating the rupee amid the balance of payments crisis, which ended as an apparent failure. The reason is that, by this time the rupee was already under heavy downward pressure which was somewhat controlled by reserve injection. Thus, the decision to float the currency was a mere removal of the support allowing for a free fall of the rupee, where the currency immediately fell by 3.7% MoM in September, compared to an average of 0.2% MoM depreciation prior to this under the support of the intervention. With the free float seeing a lack of success, the CBSL reverted to building its reserves mainly through commercial debt by issuing international sovereign bonds and SWAPS (mostly with the reserve bank of India), under the hope of inducing a recovery. Over time, the issue of bonds increased to counterbalance the steep slump of the rupee. Even though intervention was effective this was only temporary. In November 2015 the CBSL raised USD 1.5 billion worth of bonds (in addition to USD 0.65 billion in June the same year), raising the forex reserves to USD 7.3 billion at the end of the month. However, the reserves drained back to USD 6.3 billion after a mere two months, while the rupee persistently depreciated. The amount of forex reserves held in months of imports (goods and services) averaged 5 months during 2012-16.

Source: Central Bank of Sri Lanka

Source: Central Bank of Sri Lanka

Note: No bonds were issued in 2013 |

|

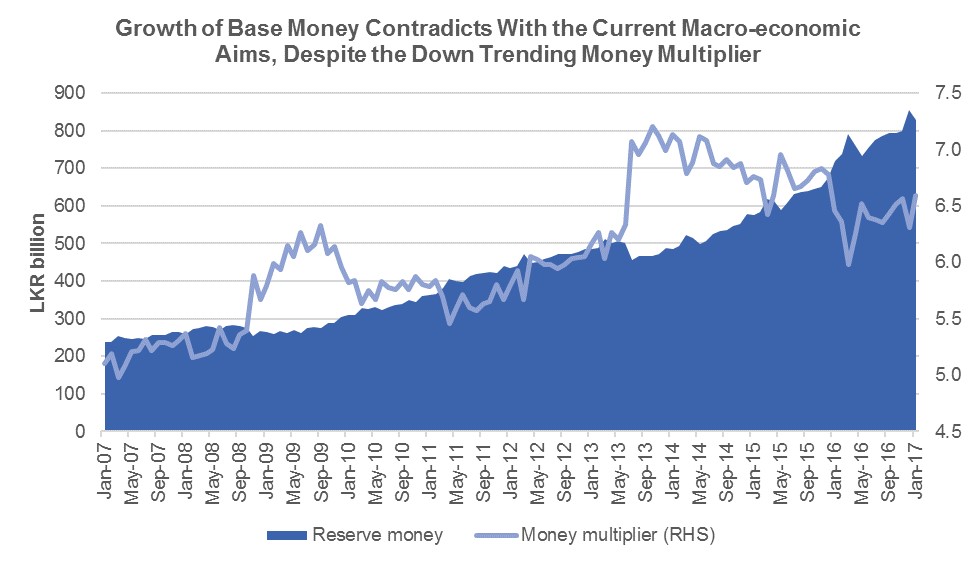

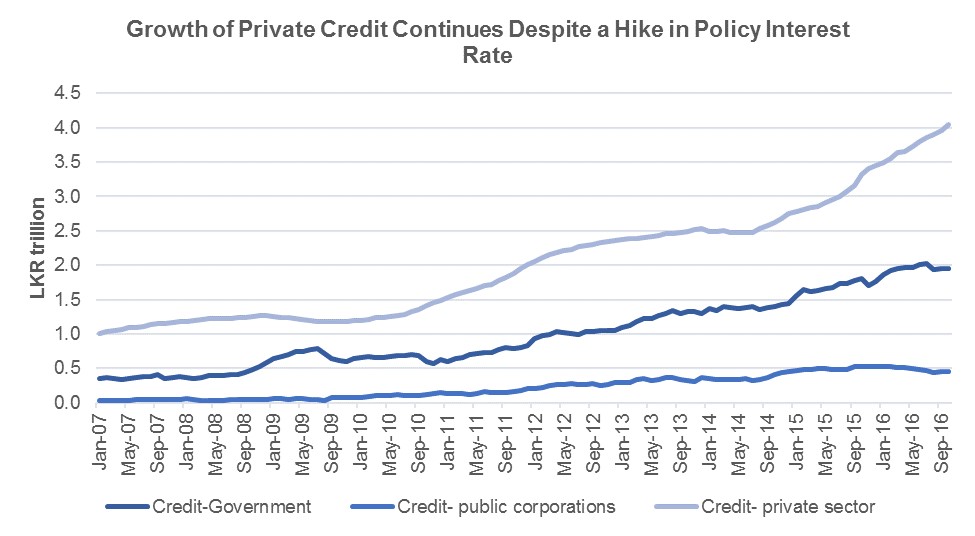

Sterilised Exchange Intervention in a Consumption Driven Economy Turns Out to be a Grave Error The reasoning for the ineffective exchange rate management is the existing monetary policy framework of monetary targeting. Even though the CBSL effectively undertook intervention in the exchange regime, it sterilised the intervention by keeping a flexible monetary policy. In other words, the decline in money supply with attempts to appreciate the LKR was neutralised by the CBSL, in spite of excess liquidity in the country. Given the character of the macro-economic environment, Sri Lanka needs a tight monetary policy to strike an increase in interest rates, reduce private credit, and sort out the balance of payments and inflation. Instead the intervention was sterilised through a combination of money printing and purchasing of treasury bills. Reserve money has increased by 27.1% YoY since the end of 2016 to LKR 856.1 billion compared to a year ago when the figure stood at LKR 673.4 billion.

Source: Central Bank of Sri Lanka

The approach to sterilise money supply on top of excess liquidity was adopted to keep policy interest rates low. This was to create more credit in the system to generate investment-led economic growth. Likewise, the policy lending rate (standard lending facility rate- SLFR) was cut to a low of 7.5% in April 2015 which caused domestic credit to leap by a compounded monthly average of 1.8% during 2015. Within the segments of domestic credit, the most significant rise was recorded in private credit which grew at a monthly average rate of 2.4% during the same period. As we see this is a landmark error given that the Sri Lanka is a consumption-driven economy with a balance of payments concern. Thus, instead of encouraging investments, consumption grew, although only part of it led to growth in domestic consumption. The residual impact was intensified imports, causing further deteriorating in the current account. Moreover, the cutback in the standard deposit facility rate (SDFR) to a low of 6.0% in last half of 2015 led to a heavier outflow of capital impacting the financial account. Thus, as per our analysis, given the macro-economic climate in Sri Lanka, the CBSL should have taken a joined stance of an exchange rate intervention along with a tight monetary policy. Instead, the sterilised intervention purely focused on exchange rate intervention causing the foreign exchange reserves to drain without a lasting impact and adding to the country’s international debt. |

|

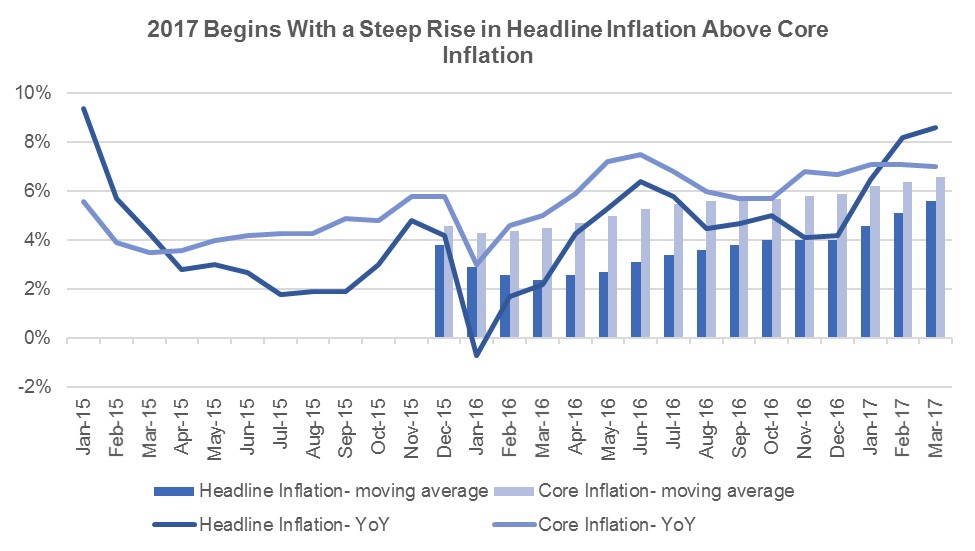

Headline Inflation on a Steep Growth Trajectory Amid Low Energy Prices; Is Walking Inflation Trouble? The prolonged increase in money supply and credit growth in the economy has the fuelled domestic consumption to grow, which is the key driver of current GDP growth. This has built increasing inflationary pressure. The current status of the Colombo Consumers Price Index (CCPI) is identified as walking inflation, where the acceptable inflation rate should be at 5% on average. As observed, Sri Lanka’s core inflation rested in the range of 5.6%-6.7% during 2015-16. However, attributed to a fall in fuel (energy) prices and declining food and beverage imports, the country’s headline inflation has been lower than core inflation rates, since March 2015. Heeding the advice of the IMF, the CBSL accepted tightening its monetary policy. From January 2016, the SLFR was increased to 8.0% and later to 8.5% and the SDFR was increased to 6.5% and then 7.0%. Simultaneously, the statutory reserve ratio (SRR) was hiked to 7.5% from 6.0%. However, despite policy changes private credit continued to grow. As a consequence, even though the inflation rate dipped temporary for a month, immediately after this, inflation accelerated. Moreover, exactly one year after the monetary policy remedies, headline inflation took a steep rise surpassing the rate of core inflation and recorded an inflation rate of 8.6% as of March 2017. Thus, even though inflation was caused by money supply growth, currently, inflation stands unresponsive to the monetary policy remedies, which is a serious concern for the country. On this note, a high inflation rate of 8.6% is a definite constraint on consumption, consequently on the Sri Lankan economic growth.

Source: Department of Census and Statistics

Note- Statistics are according to new base year in 2013

Source: Central Bank of Sri Lanka

The way forward planned by the CBSL is to completely transform its monetary policy from a monetary targeting framework to an inflation targeting mechanism. Our conclusion is in support of this change and we believe that further contraction of the monetary policy, alongside other reforms would boost exports and investment. The final outcome should be a further reduction of the money multiplier, such that the growth of reserve money (to pay debts) would not result in inflationary pressure. |

|

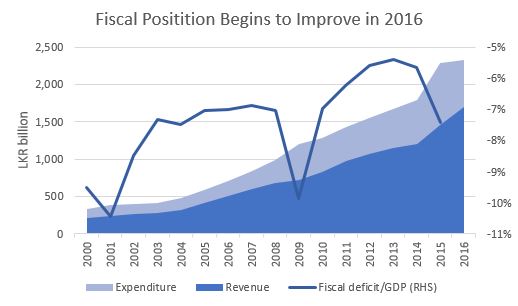

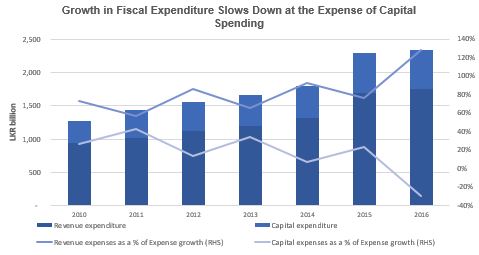

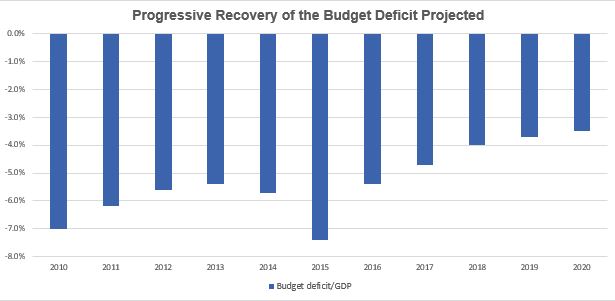

Fiscal Position Makes a Turnaround in 2016; Suits Sustainability? Analysing the timeline of the fiscal position, the country had been in deficit over a prolonged period, even prior to the 90s. Over the period 2005-15, the deficit has worsened by close to five-fold reaching LKR 829.5 billion, 7.4% of GDP. A key element of the burden on the fiscal deficit is the subsidies utilised to support the loss-making state owned enterprises (SOEs) including the Ceylon Petroleum Corporation, Sri Lankan Airlines, Sri Lanka Ports Authority and Ceylon Electricity Board. As part of the central government’s obligation to primarily support these SOEs, subsidy expenditures have grown at a CAGR of 16.4% over 2010-15, and stood as the second highest expense contributor to the increasing fiscal expenditure over the period. Further, the fiscal history has witnessed an exceptional surge in the deficit in 2010 and 2015. The latter is resultant of the 24.4% salary growth granted (the largest cost centre of the fiscal operations) post presidential election by the new Maithripala government to public sector employees. In terms of revenue mix, 93.2% of revenue relied on tax income. Even though revenue was less supportive in improving the fiscal deficit, it is worth to note the increasing weight placed on indirect taxes. As of 2015, 75.1% of the revenue was from indirect taxes against 70.0% in 2012. The contribution to total revenue by indirect taxes has been persistently intensifying contributing 92.8% of revenue growth in 2015, compared to 57.4% in 2012. However, the increase in indirect taxes only met 48.7% of the 2015 expenditure growth. The prolonged deficit has intensified the country’s fiscal debt burden at a CAGR of 17.0% over 2005-15 (excluding a marginal decline in 2010). Nonetheless, 2016 marked an important milestone in the country’s fiscal history by reversing the long standing trend. In 2016, with the support of 124.4% YoY growth in non-tax revenue and 8.0% YoY growth in tax revenue, Sri Lanka’s fiscal operations secured 15.9% YoY growth in revenue topping a mere 1.9% YoY growth in expenditure. Even though Sri Lanka is still tax oriented in its fiscal revenue, only 46.4% was contributed to revenue growth by taxes while non-tax revenue injected 53.0% of the revenue growth. On the flip side of this strategy is the, 2.1% YoY reduction in capital expenditure, out of which public investment was reduced by 1.5% YoY. This is the first-time, after 2002, the the Sri Lankan fiscal plan reduced attention to capital spending. On the contrary, revenue expenditure grew by 3.3% YoY, making up 129.1% of the total fiscal expenditure growth. As a result, increased revenue expenditure fuelled domestic consumption while triggering a growth in private credit in spite of a rate hike. All in all, the fiscal deficit in 2016 was reduced by 22.8% YoY (estimated to be 5.4% of GDP), which moderated the growth of government debt. As per projections of the department of fiscal policy and department of national budget, the budget recovery is to continue to reach 3.5% of GDP by 2020.According to our point view, while the revenue-based fiscal consolidation is supportive, its sustainability is questionable due to the longer term economic impacts of the decline in capital expenditure. This judgement is based on the context of an economic growth decline on the one end and its consumption driven nature on the other. A sluggish economy should not be allowed with high growth in consumption without a balanced injection of investments. This is also necessary to sustain ongoing revenue for fiscal operations. Additionally, the increasing revenue expenditure will further aggravate consumption resulting in an increase in the likelihood of a crowding-out private credit, furthering inflation and an imbalanced macroeconomic environment.  Sources: Ministry of Finance, Central Bank of Sri Lanka

Note: 2010 onwards, based on GDP estimates compiled by the Department of Census and Statistics (DCS) under the base year 2010

Sources: Department of Inland Revenue, Sri Lanka Customs, Department of Excise, Telecommunications Regulatory Commission of Sri Lanka, Department of Treasury Operations, Department of State Accounts, Department of Fiscal Policy and Central Bank of Sri Lanka

Source: Ministry of finance

Note: Figures from 2016 are estimates |

|

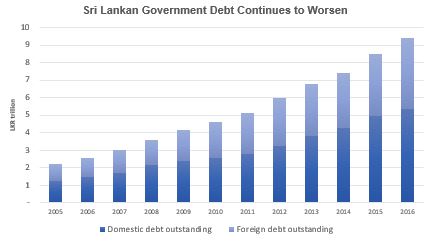

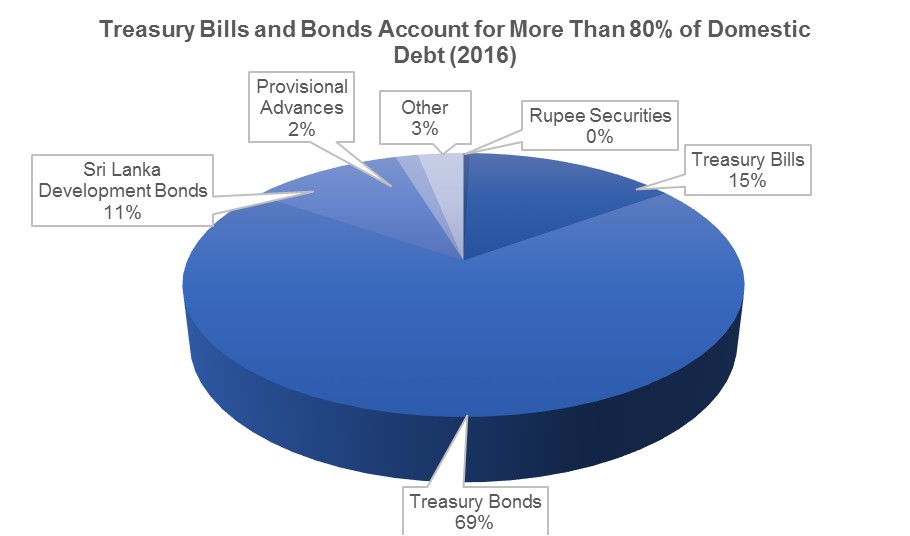

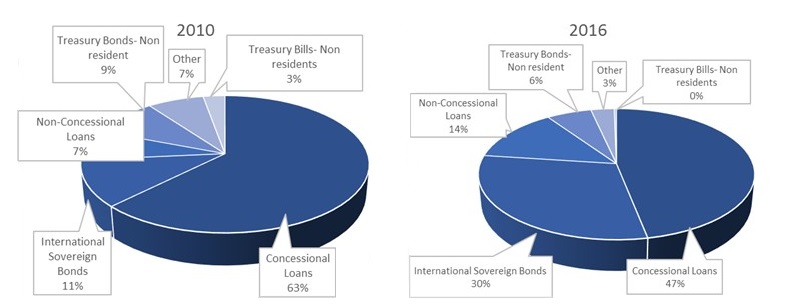

Overall Debt Mounts With Increasing Reliance on External Funding Sources Of the many effects of economic policy adopted, one of the most significant has been the upward pressure on the level of outstanding government debt, which reached LKR 9.4 trillion as of 2016, a two-fold increment from 2010. Domestic debt accounted for 56.0% of this figure while the rest was held by foreign parties. Till 2015, mostly domestic debt was issued to finance the Sri Lankan fiscal operations, accounting for 71.5% of the deficit. However, in 2016, 67.0% of debt was financed through foreign debt while the residual 33.0% was issued domestically. The reliance on foreign debt is increasing, attributed to the CBSL’s exchange intervention mechanism, which is mostly financed through sovereign international bonds. As of 2016, international sovereign bonds accounted for 30.2% of the foreign debt portfolio compared to 10.9% in 2010. In terms of domestic debt, 18.1% was short-term while 81.9% was medium and long term. Due to this the rollover risk of debt is low. Moreover, treasury bills and bonds consisted of 84.1% of the total domestic debt. Of the overall debt, 15.1% was outstanding loans used to finance the SOEs, where 94.6% was accounted for by four SOEs (Ceylon Petroleum Corporation (CPC), Ceylon Electricity Board (CEB), the Sri Lanka Ports Authority (SLPA), and Sri Lankan Airlines). As a consequence of the escalating debt, interest expense has grown at a CAGR of 7.6% over 2010-15.

Sources: Ministry of Finance, Ministry of National Policies and Economic Affairs, Central Bank of Sri Lanka

Sources: Ministry of Finance, Ministry of National Policies and Economic Affairs, Central Bank of Sri Lanka

Sovereign Bonds Grow in Importance Within Foreign Finance

Sources: Ministry of Finance, Ministry of National Policies and Economic Affairs, Central Bank of Sri Lanka |

|

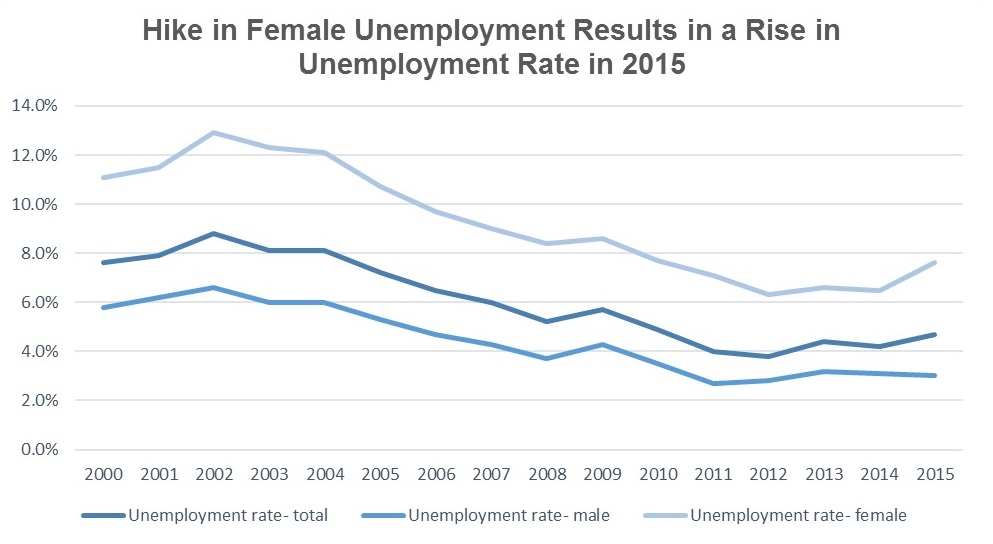

Unemployment Begins to Impact the Educated and Female Workforce, While the Tertiary Sector is the Dominant Employer A further attribute of the imbalanced microenvironment was seen through the labour market. The labour force of Sri Lanka, in 2015, stood at 53.8% of the Sri Lankan population above the age of 15 (economically active population), a decline from 57.1% in 2006. Meanwhile, the unemployment rate was recorded at 4.7%. The country has witnessed a continuous decline in unemployment since cessation of the civil war (except in 2013) due to the strong economic growth achieved by the country. Even though female unemployment was comparatively high, trends were similar for both genders over the period and female unemployment registered a larger fall over the period, resulting in an improvement in gender equality in the country. However, in 2015 the gender gap widened with an upsurge in female unemployment by 1.1 PPTs while male unemployment dipped by 10 bps. Thus, even though overall unemployment witnessed a steep rise, the impact fell squarely on the female population.

Source: Department of Census and Statistics

Note- Excludes Northern and Eastern provinces

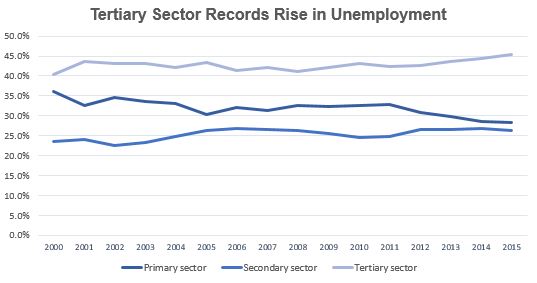

The service sector is the largest employer in the country followed by the primary and manufacturing sectors, as of 2015. Even though the primary sector generates the lowest level of economic activity, it remains the second largest employer as a result of the government subsidies used to uplift and sustain the sector. However, over the past there has been an ongoing decline in the proportion of employment in the sector to 28.6% in 2014 from 32.9% in 2011. In contrast, manufacturing employment has grown during the same period to 26.9% from 24.7%. Nonetheless, in 2015 both declined while the service sector drove employment growth, increasing to 45.3% of the total employed in 2015 from 42.4% in 2011, driven by rising service sector economic activity.

Source: Department of Census and Statistics

Note- Excludes Northern and Eastern provinces

The chart represents % of employment by primary, secondary and tertiary sectors

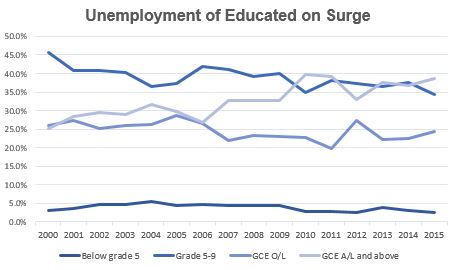

Prevailing unemployment also corresponds to the burgeoning unemployment of the educated workforce of Sri Lanka. Unemployed people with educational qualifications above GCE Advanced level (A/L) stands the highest as of 2015, accounting for 38.7% of the total. However, unemployed people with lower secondary education (grade 5-9) are also a concern in the country due to Sri Lanka’s less developed industrial sector, which is the typical source of employment for those with secondary education. This could also be read as a negative impact from an atypical pattern of structural change (development usually happens in a sequence starting with the primary sector through the industrial sector and finally the tertiary sector), where Sri Lanka is a service-led developing economy. Even though the growth of the service sector is crucial for the labour market, a lack of attention on the industrial sector is a source of unemployment given the country’s resource endowment.

Source: Department of Census and Statistics

Note- Excludes Northern and Eastern provinces

The chart represents % of unemployment by level of education |

Political and Legal Overview

|

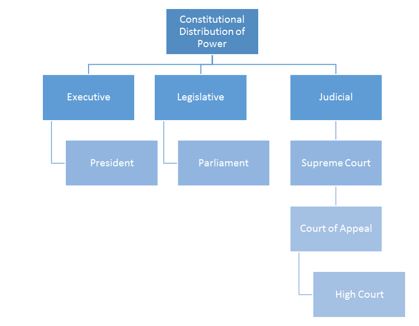

Sri Lanka: State of Extreme Executive Power The Sri Lankan constitutional timeline dates to the British colonial era and the Donoughmore Constitution, which marked a major turning point in the island’s political development. The constitutional reform was implemented by a royal commission headed by the Earl of Donoughmore in 1931, to adopt adult suffrage as a means to construct a self-governing structure. This was later replaced by the Soulbury Constitution, approved in 1946, which became the basic document of Ceylon’s (as Sri Lanka was then known) government when the country achieved independence on 4th February 1948. It established a parliamentary system modelled on that of Britain and was quite similar to the constitution adopted by India in 1949. Only after 23 years of independence, in 1972, did the country adopt its own republican constitution, which changed the formal name of the country from the Dominion of Ceylon to the Republic of Sri Lanka. The constitution also recognised Sinhala as the sole national language by abandoning the notion of a secular state in the former constitution. This was the starting point for the Tamil minority to espouse an independent state with the emergence of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), leading to a 26-year civil war which ended in 2009. In 1978, Sri Lanka adopted its second republican constitution changing the official name to the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, which is the present document governing the country. Besides the other substantial reforms from the 1972 constitution, it adopted Tamil as an administrative language and made English the third language of the country, while maintaining Sinhala as the official language.

Source: UZABASE

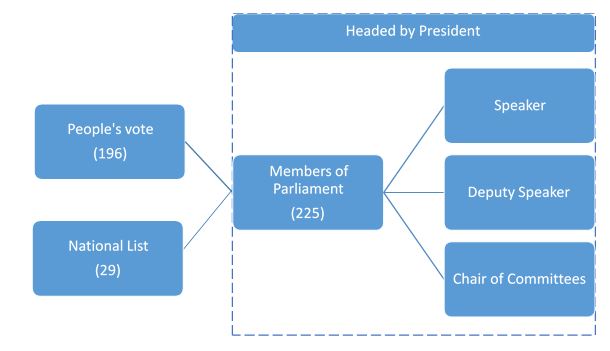

Today, the Sri Lankan constitution stands on the nineteenth amendment as a consequence from the election manifesto of President Maithripala Sirisena, of a 100-day programme of constitutional and governance reforms. Despite the radical changes sought by the government in the nineteenth amendment concept paper, under all three branches of the executive, legislative and judicial power; the finalised constitution bill remained similar to the 18th amendment with minor changes and restored areas of the 17th amendment. The executive branch is ruled by the president of Sri Lanka, who is the head of the State, Government, and the Armed Forces. He is elected by a direct vote of the people for a five-year term for a maximum of two terms. The executive presidency can appoint the Prime Minister; The prime minister’s power takes an advisory role to the president to determine the ministers of the cabinet and other ministers; the ministries; and the assignment of subjects and functions to such ministers. The legislative power of Sri Lanka is unicameral, with a Parliament of 225 members elected to five-year terms; The President can dissolve Parliament at any time, which significantly weakens the legislative authority vis-a-vis the Executive branch. The main purpose of the Parliament is to pass bills and resolutions. This legislation becomes law upon a majority vote and the endorsement of the Speaker. However, if the Cabinet or the supreme court requires the approval of the people, the bill may require a referendum, which the President must endorse. No court can question a law adopted in this way. Parliamentary System of Sri Lanka

Source: UZABASE

The judicial branch of Sri Lanka is comprised of a Supreme Court, a Court of Appeals, a High Court, and other courts created by law. The executive presidency assumes the appointment of the Chief Justice, members of the Supreme Court, and the President and Justices of the High Court. The Supreme Court holds the sole power of constitutional review, and its jurisdiction also extends to matters concerning fundamental rights, final appeals, and election issues. It also has the power to review the actions of Parliamentary members and may advise Parliament in the legislative process. Branches of Power in Sri Lanka

Source: UZABASE

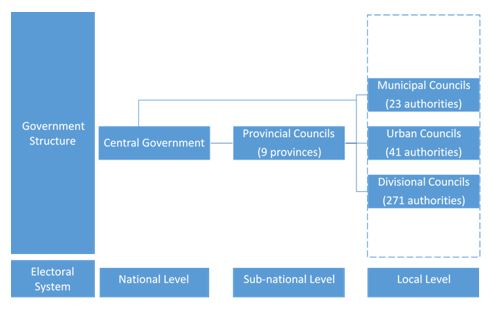

The government is structured under three levels consisting of the central government, provincial council and the local government, with sequential distribution of power. The electoral system which maintains the government is maintained at a national level, sub-national level and local level. The presidential and parliamentary elections are held at the national level, acquiring the vote of all citizens of Sri Lanka. The sub-national elections are employed for provincial councils while at local level, elections are held for appointments to municipal councils, urban councils and division councils (known as pradeshiya sabhas). The responsibility of the local government rests on maintenance of regulation and administration, promotion of public health and sanitation; consideration for environment sanitation (clean water, air and efficient waste disposal), and public thoroughfares and public utility services. Structure of the Government and Electoral System of Sri Lanka

Source: UZABASE |

|

The Emergence of the Politics of Mixed Coalition, Defeats the Long Hold of Socialism The Sri Lankan political landscape is dominated by two parties, namely the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) and United National Party (UNP). The United People’s Freedom Alliance (UPFA) led SLFP, first came into power in 1956 (upon inception in 1951) under the Bandaranaike term of office and held executive power till 1977. The party held a positive attitude towards nationalisation and public sector, and recognised socialism, while the pro-capitalist UNP was more concerned with motivating the participation of the private sector. Post-1977, the executive power exchanged hands with the opposition gaining power for a period of 17 years, lasting till 1994, during which the executive presidency was constitutionalised. However, subsequently, the SLFP regained its dominance in the government, continuing in power till 2015, initially under the Bandaranaike regime followed by the Rajapaksa Regime. Former President, Mahinda Rajapaksa, received the people’s vote for the first term of office, due to his electoral manifesto to end the 26 years of civil war. Upon declaring the war closed in 2009, he received significant goodwill as a man of his word, which allowed a convincing win for the second term of his executive presidency, during the 2010 presidential elections. However, this popularity did not last long enough to ensure a third term of office. The era starting in 2015 marked the beginning of a period of political turmoil in Sri Lanka. The opposition UNP formed a united coalition along with other minority political parties and some members of the SLFP, to bring the former SLFP Parliamentarian Maithripala Sirisena, as a common candidate to head the state. The main political manifesto of this movement was good governance (Yahapalana) within 100 days, mainly with the promise of reforming the current presidential constitution to a parliamentary constitution by abolishing the executive presidency. Hunger for change in Sri Lanka drew 51.3% of total votes towards the “Yahapalana” with Rajapaksa defeated, securing only 47.6%. The initially proposed change to the executive branch was for the president to be head of the state but the government to be headed by the prime minister. The misalignment in this proposal was that the president would act on the advice of the prime minister but be appointed by a direct vote of the people, which is unusual among parliamentary constitutions in practice. The change to the mode of election was reserved for the next parliament. However, the reform overall was not passed on to the nineteenth amendment due to severe objections from the parliament majority and the supreme court opinion on the necessity for a referendum. Nonetheless the failure to alter the executive presidency, some positives of the nineteenth amendment include the repeal of the urgent bill procedure, where bills were allowed to be passed through the cabinet via a fast-track process, which was often manipulated. Secondly, there was the restoration of the constitutional council and independent commissions, which governs the nation in areas of public service, judiciary, the police, elections, human rights, bribery and corruption, audit, and procurement. Even though these reforms are directed at good governance, their effectiveness at extinguishing authoritarianism and corruption is still unclear. Moreover, reforms such as increasing the age requirement to compete in presidential elections from 30 to 35, stand as counterproductive reforms in the name of good governance. This prevents Namal Rajapaksa (son of former president) competing for presidential election in 2020, who is the only eligible candidate to resume the Rajapaksa regime. On the whole, even though minor amendments have been added improving governance, Sri Lanka has yet to experience the change sought by its people. |

|

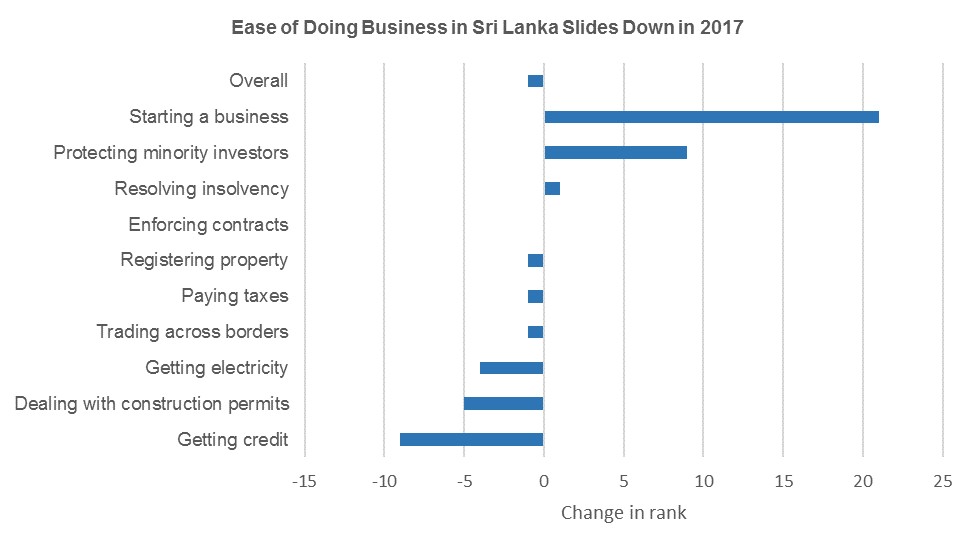

A Decline in the Rank of the Ease of Doing Business in Sri Lanka, Despite Capitalism in Power The political interest in promoting the business environment in the country has been active throughout all governments, mainly through foreign investments. The present coalitional government, which includes the capitalist UNP was a victory for the private sector that increased confidence in the business environment, even though its strategies are yet to be clearly defined. Current Board of Investment (BOI) policies allows for full foreign ownership across almost all areas of the economy on foreign investments and promotes investment in key areas including tourism and leisure, agriculture, export manufacturing, export services, apparel industry, infrastructure, knowledge services, utilities and education. The attention to international trade and investment has led the country to secure bilateral agreements with 28 countries and double taxation avoidance agreements with 38 countries. All these agreements are secured by the Sri Lankan constitution. Moreover, the Sirisena government has initiated an “ease of doing business” forum, under the supervision of the Ministry of Finance, which aims to collaboratively solve any issues encountered by businesses in Sri Lanka. Despite all efforts thus far, Sri Lanka is ranked third in South Asia for ease of doing business and 110th globally, according to the World Bank’s ease of doing business index 2017. The World Bank report analyses the regulatory environment affecting ten areas in the lifecycle of a business in 190 countries: starting a business, dealing with construction permits, getting electricity, registering property, getting credit, protecting minority investors, paying taxes, trading across borders, enforcing contracts and resolving insolvency. The government reforms to improve the business climate have been of minor significance, leading to a consecutive decline in rank since 2012 from the 81st position. Per the World Bank, the dip is a result of the falling rank of Sri Lankan regulation with respect to the credit system, obtaining construction permits and getting electricity. In the matter of the credit system, Sri Lanka was particularly below the South Asian average, as to legal rights of both creditors and debtors. The law doesn’t prioritise payment to creditors over tax claims and employee claims in the event of bankruptcy, the law doesn’t entirely accept movable assets as collateral and the country lacks a public credit registry (which is less developed in South Asia overall). However, credit bureau (which holds information confidentially), covers information of 57.2% of adults in the country, while the South Asia was on an average of 14.0%. But this information has not been a value add to financial institutions to assess the credit worthiness and the information excludes debtor data from retailers and utility companies, which prevents the Sri Lankan credit system from integrated and unified functioning. Apropos, construction permit regulation, Sri Lanka has speedy procedures (in terms of number and days) and low cost, compared to the South Asian average and also the OECD average (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development is a forum of 34 governments with market economies aiming to promote economic growth, prosperity, and sustainable development). But the system fails vis-à-vis the quality of construction. There are no legislative requirements to assess the quality of construction before initiation and during construction. Review of a construction plan is done solely by civil servants and there is no review by a third-party entity (where review by a licensed architect/engineer is a best practice followed globally including in South Asia), causing the system to often be manipulated. Moreover, no party is required by law to be held liable for structural flaws and problems and accountable to obtain insurance. Attributed to the low quality of the construction permit system, there have been several incidents of damage, even risking lives. However, politics is yet to place its attention on the same.With regard to regulation on trading across borders (both exporting and importing), Sri Lanka is ranked third in South Asia as of 2017, even though the country has slid down a rank in the same. Few areas of improvement in regulations were made for starting new businesses and protecting minority investors. The reform that led to an improvement in regulation ranking for starting a new business was the elimination of stamp duty on newly issued shares. The cost, time and procedures required for a new business start-up in Sri Lanka was above the South Asian average, as per the World Bank’s doing business survey. On the other hand, Sri Lanka’s ranking for protecting minority investors improved due to the reform requiring board or shareholder (in some cases) approval of related-party transactions and to undergo an external review. Sri Lanka also stood above the South Asian average, for protection of minority shareholders.

Source: World Bank: Ease of doing business 2017

Note: The chart represents the change in rankings between 2017-16 |

|

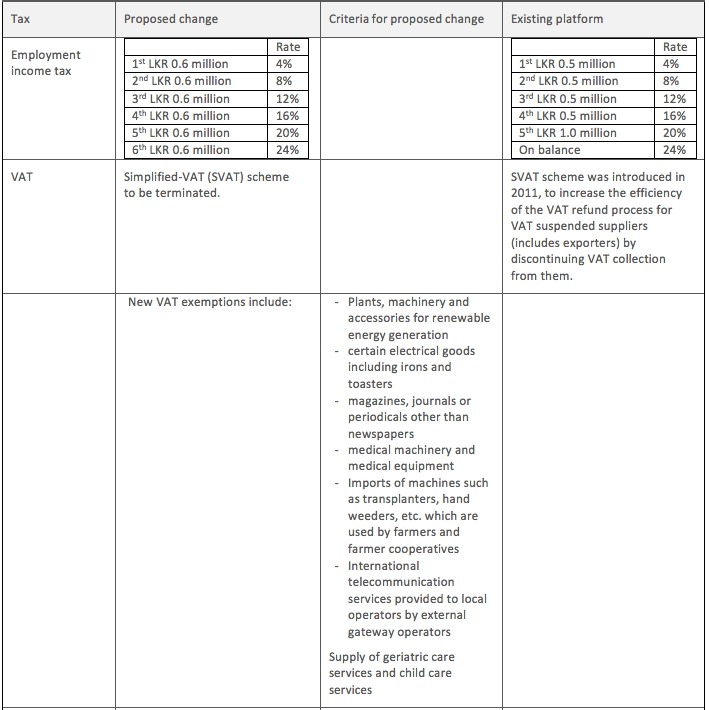

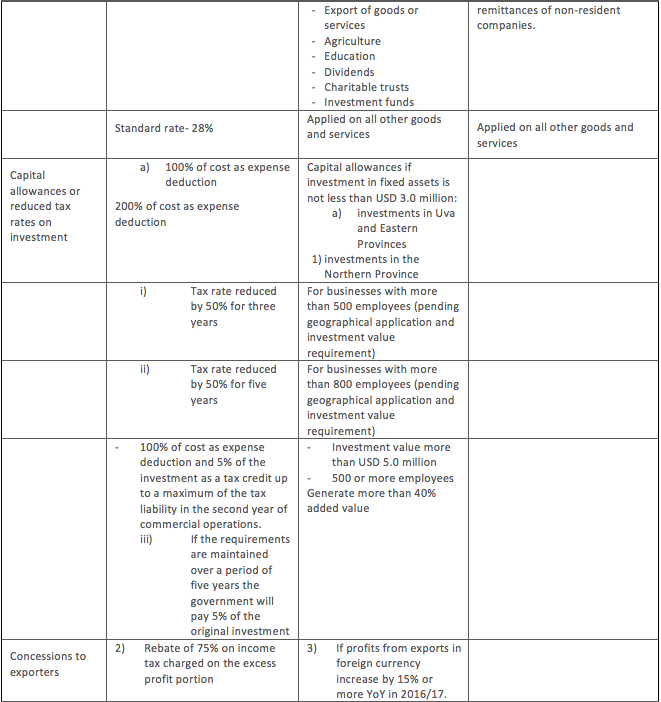

A Tax System for Good Governance and to Incentivise Investment The proposed budget of 2017, centered around the theme “accelerating growth with social inclusion”, consisted of a new scheme including investment incentives and better tax governance. The motive behind better tax governance is to boost the declining tax/GDP ratio to a level sufficient to cater to government expenditure and debt, by increasing tax revenue. The changes in the employment tax allow for more spending, however, the budget’s aim to eradicate poverty depends on the effectiveness of the distribution of revenue, which is less likely given the current focus of the government to reduce the country’s external debt. The rest of the tax reforms largely aim at revamping the export sector of the country and encouraging start-ups. With these changes, the government is taking steps towards the development of the Uva, Eastern and Northern provinces, while supporting their aim to make Trincomalee port a world-class port city. If execution is as planned, this will allow a strong trade corridor to be built throughout Sri Lanka empowering growth through exports. Note: PLEASE REFER APPENDIX TO POLITICAL AND LEGAL OVERVIEW FOR MORE INFORMATION |

Financial Overview

|

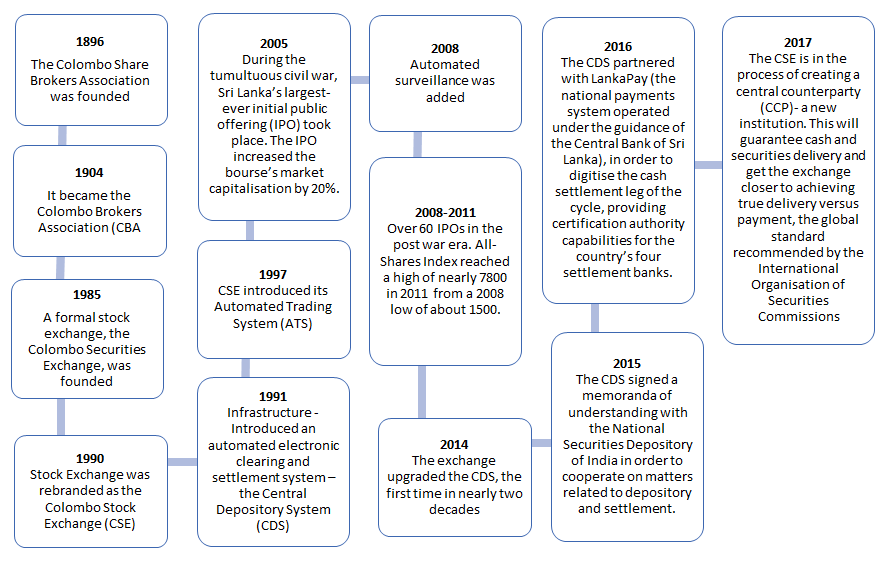

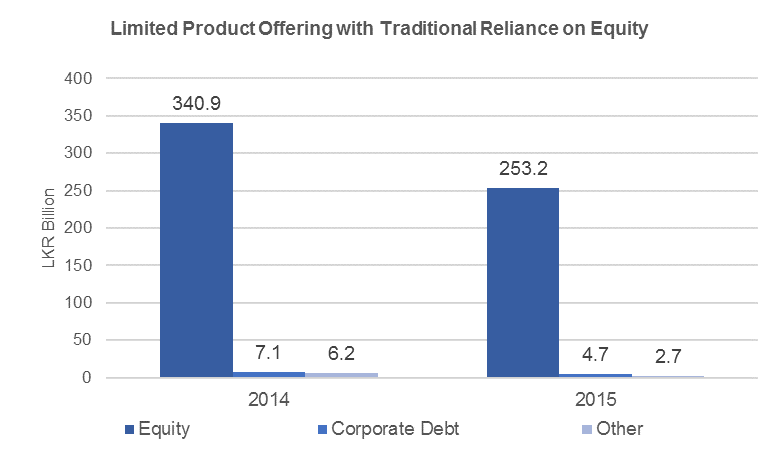

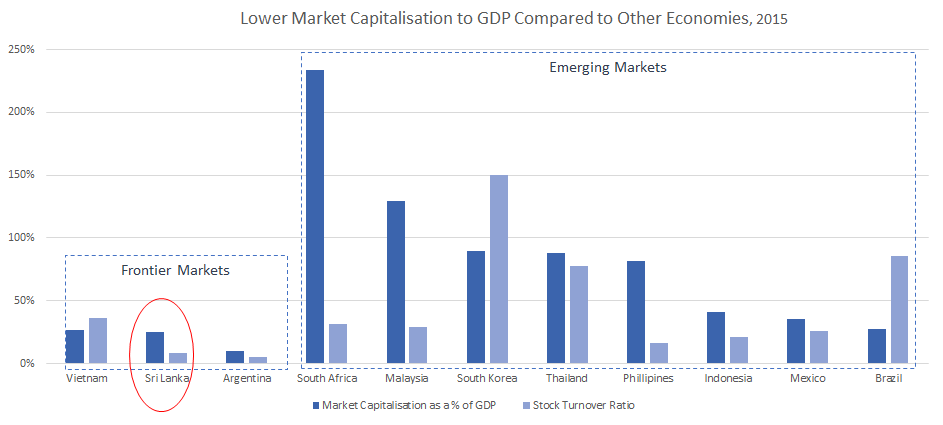

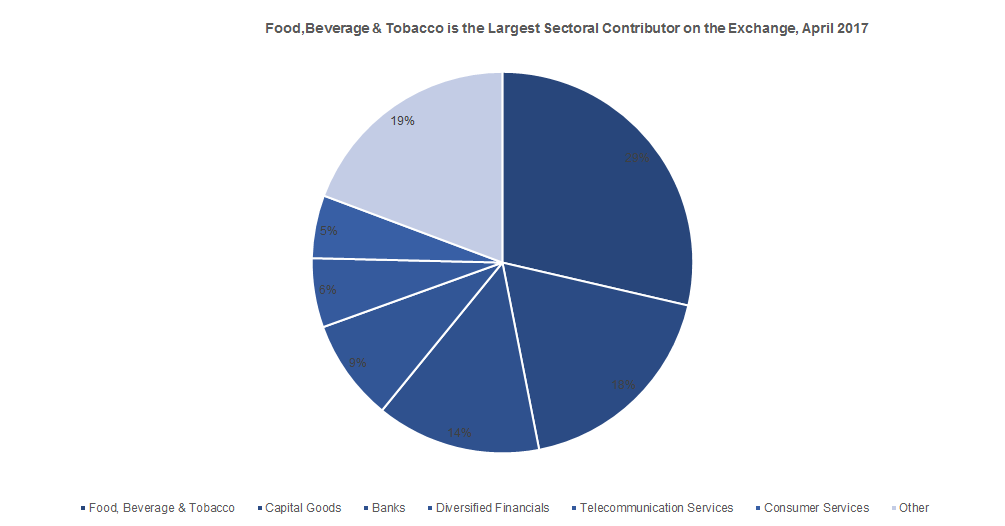

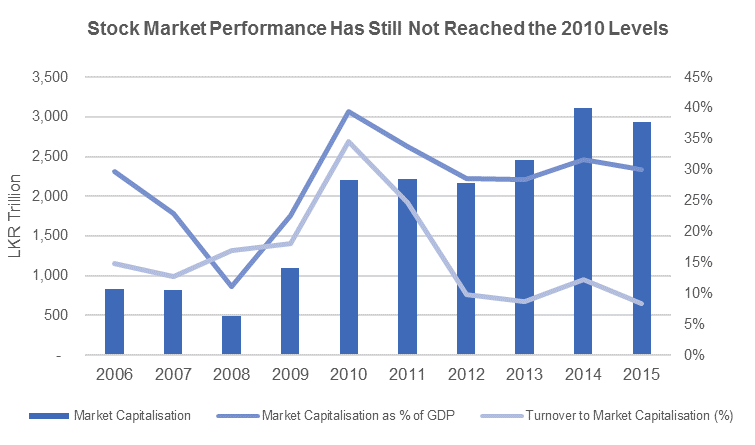

Sri Lanka as a Frontier Market has High Growth Potential Capital Market in Nascent Stage Mainly Due to The Low Level of Market Participation The capital market in Sri Lanka is characterised as a market with limited product offering where traditional reliance is placed on equity. The country is still classified as a lesser developed “Frontier Market” with characteristics such as low market capitalisation, low liquidity, and higher volatility warranting a higher premium for foreign investors. The market infrastructure at the Colombo Stock Exchange (CSE) has not kept pace with developments at other stock exchanges in the region, in terms of trading and settlement systems and demutualisation of the exchange. Resultantly the country displays a relatively low stock market capitalisation to GDP (25.3%) and low level of liquidity (8.6% stock turnover ratio), when compared to frontier markets such as Vietnam (26.8%, 36.0%) and emerging markets such as South Africa (234.0%, 31.8%) and Malaysia (129.3%, 29.1%). As of 2015, Sri Lanka’s stock market had approximately 294 listed companies in 20 business sectors. Sri Lanka, which is a social market economy needs to place high importance on capital markets, which if efficient, will lead to a resourceful financial system and benefit the economy in terms of rising economic growth, macroeconomic stability and reduction in poverty. Key Developments in the Stock Market Since 1896

Source: Oxford Business Group and other Sources

Source: Securities Exchange Commission (SEC) Sri Lanka.Note: Based on the annual turnover by product.

Source: Securities Exchange Commission (SEC) Sri Lanka, World BankNote: The liquidity is based on the stock traded turnover ratio of domestic shares as calculated by the world bank on a consistent basis across all countries.

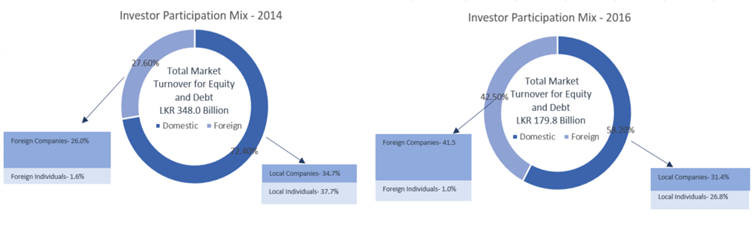

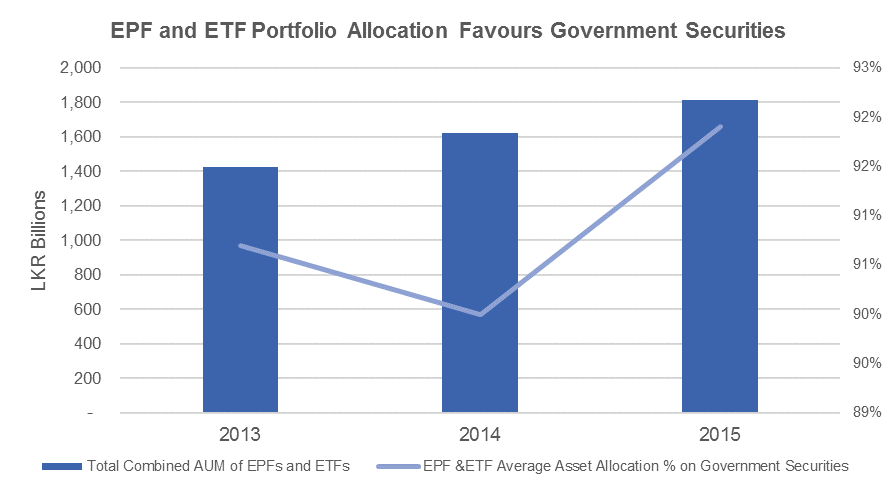

The main challenge Sri Lanka faces in making its capital market more broad-based and vibrant is its inability to attract market participation. Politics which replaces economic considerations results in more unprofitable and counterproductive investment projects that reduce the wealth of the nation, discouraging market participation. Market participation can only be improved if the environment encourages it. According to Oxford Business Group estimates, only about 25,000 Central Depository System (CDS) accounts trade actively out of a total of 750,000 accounts (implying only 3.3% active participation). However, the capital market in Sri Lanka is in the process of broad-basing its investor participation with a changing investor participation mix. Moreover, the country also aims to increase participation by long-term institutional investors such as Employee Provident Funds (EPFs) and Employee Trust Funds (ETFs), which would support in improving market stability and sustainability. Sri Lanka Anticipates Broad-basing of Investor Participation

Source: Securities Exchange Commission (SEC) Sri Lanka

Source: Securities Exchange Commission (SEC) Sri Lanka

Source: Colombo Stock Exchange (CSE) Weekly Report- YTD (21/04/2017) 2017 |

|

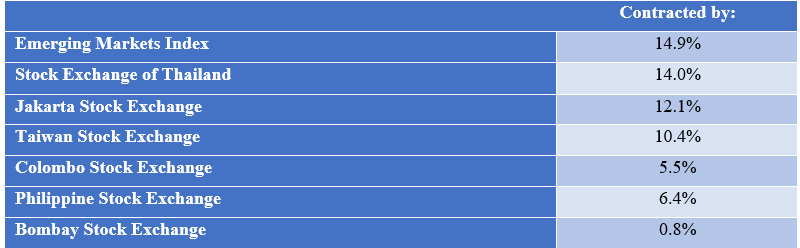

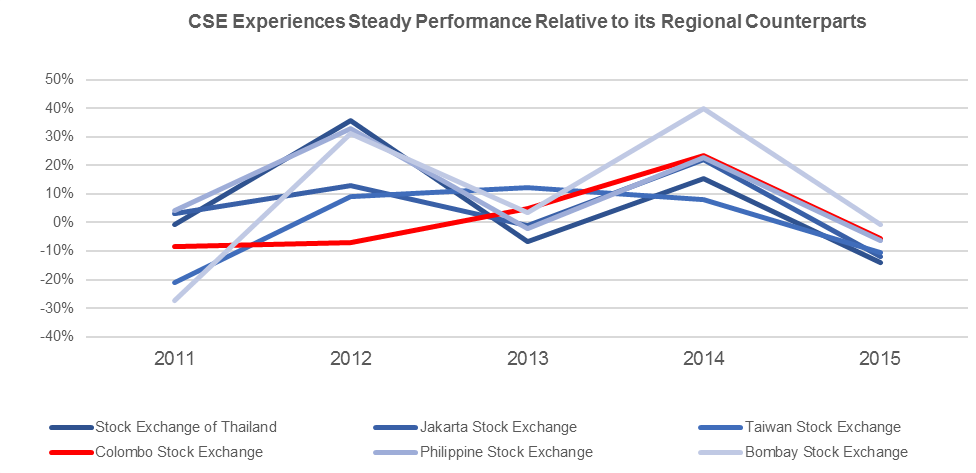

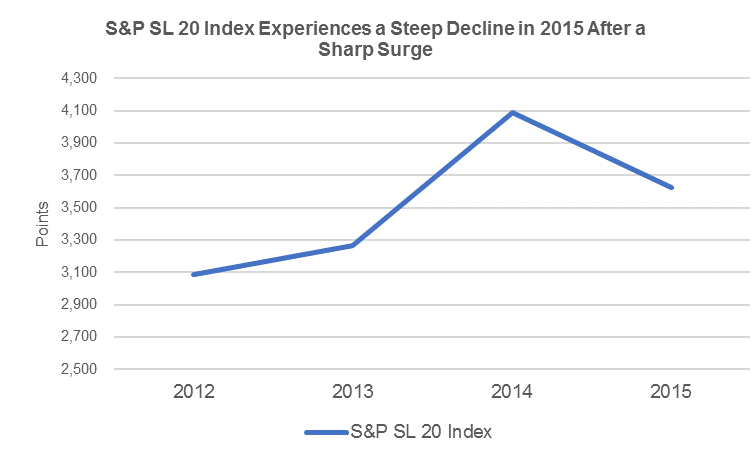

Prospects for Long-Term Capital Market Growth Looks Promising 2015 – A Bad Year for Stock Markets Worldwide; CSE Holds Relatively Better The Stock market worldwide experienced a hard year in 2015, with declines in index returns. Likewise, the Colombo Stock Exchange (CSE) was no different, declining by 5.5%YoY in the year under review. However, the CSE performed better than certain East and South Asian Exchanges. In Sri Lanka, the volatility in the local interest rates and the two elections that were held in 2015 also impacted stock market in the country. Prior to 2015, the CSE experienced steady performance when compared to its regional counterparts, mostly during 2011-13. Relatively Low Decline in Returns by the CSE in 2015

Source: Colombo Stock Exchange (CSE) Annual Report 2015Note: CSEALL- ASPI is the major stock market index with the performance of all companies listed in the CSE. S&P SL20 is a stock market index, based on the performance of 20 leading publicly traded companies listed in the Colombo Stock Exchange.

Source: Colombo Stock Exchange (CSE) Media Release 2014Note: Statistics for 2014 has been obtained from various sources and includes calculations

Source: Yahoo Finance, UZABASE

Source: Colombo Stock Exchange (CSE) Annual Report 2015

Source: Colombo Stock Exchange (CSE) Annual Report 2015

Source: Colombo Stock Exchange (CSE) Annual Report 2015

New SEC Act Together with SEC’s ‘Capital Market Strategy 2020’ To Foster Capital Market Development Sri Lankan capital markets are recovering after periods of instability. The stock market which experienced a boom during the post-war period, fell back as regulation was unable to keep up with the surge in activity. However, with the new government in power, the Securities Exchange Commission (SEC) has put forward a roadmap focused on updating the rules and developing key market infrastructure. The exchange and the regulator are being revamped, making it easy to attract and deploy the capital Sri Lanka needs.The SEC has released its ‘Capital Market Strategy 2020,’ with the aim to establish a robust and facilitative regulatory environment and nurture capital market development. This transformative plan for the capital market is being rolled out along with a new SEC Act. Source: Securities Exchange Commission (SEC) Sri Lanka |

|

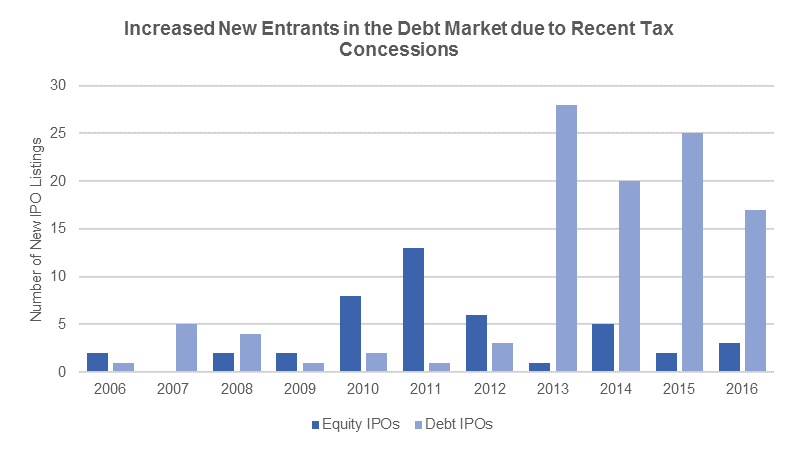

Favourable Policy Reforms to Broaden Debt Market in Years to Come The active operation of the bond market in Sri Lanka commenced in the 1990s from the issue of medium and long-term bonds, both by the government and the corporate sector. With financial sector reforms, together with the restructuring programme implemented in the last decade, the bond market operation has accelerated to 17 debt issues in 2016 from only 1 issue in 2006 (a more than 10 fold increase). In 2016, there were only 17 corporate listed debt issues, a decline by almost 32% from a high of 25 issues in 2015. The increase in debenture issues in 2015 by 25.0% YoY was mainly due to the expiry of tax exemption by the end of the year. The highest ever issue was made in 2013, at a total of 28 debt issues. Moreover, the 2016 Budget which waived off income tax and withholding tax applicable to debentures further facilitated the expansion of the corporate debt securities market in the country. Further in 2016, the finance minister in the country proposed to set up a ‘Bond Clearing House’, primarily for transactions in government securities (since the CSE does not have a trading platform for government securities), which could then be extended to other instruments, including corporate debt securities known as debt exchanges. Such expansions and concessions will positively impact the corporate debt market.

Source: Colombo Stock Exchange (CSE) Annual Report 2015 |

|

Sri Lankan Capital Market to Develop Shariah Compliant Share List Sri Lanka, which is not well known for the Islamic finance market when compared to countries like Malaysia, is now developing the Islamic finance market with the establishment of shariah stocks. Shariah means the Islamic Law together with moralities, ethics and guidelines followed for a complete way of human life. In Sri Lanka, Shariah-conscious investors and other interested groups benefitted by the country’s first fully fledged Islamic commercial bank, which was inaugurated by the central bank governor in August 2011. The country now comprises several Islamic financial service providers in the form of investment companies, leasing companies and subsidiaries of finance companies. Shariah conscious investors have the opportunity to invest in the Colombo Stock Exchange (CSE), by participating in Islamic funds such as Amana-Namal Equity Funds and unit trust such as ‘Crescent I-fund’ (is an open ended Shariah compliant fund). Furthermore, Islamic finance has been identified as a golden opportunity for economic growth in the country. On a related note, during 2015, the CSE as a risk mitigation mechanism announced the introduction of a shariah index, to prevent the CSE from generating low turnover returns due to the lack of product diversity. During 2011, Lanka Securities, a Sri Lankan stock broker introduced a shariah compliant share list in line with the requirements set by both local and foreign Islamic investors on the CSE. This was the starting point on the development of shariah compliant investments, with about 56 shariah compliant companies listed in the CSE (almost 20% of the total number of companies listed on the CSE). Institutions Offering Islamic Finance Services in Sri Lanka, February 2013

Source: Word Press |

|

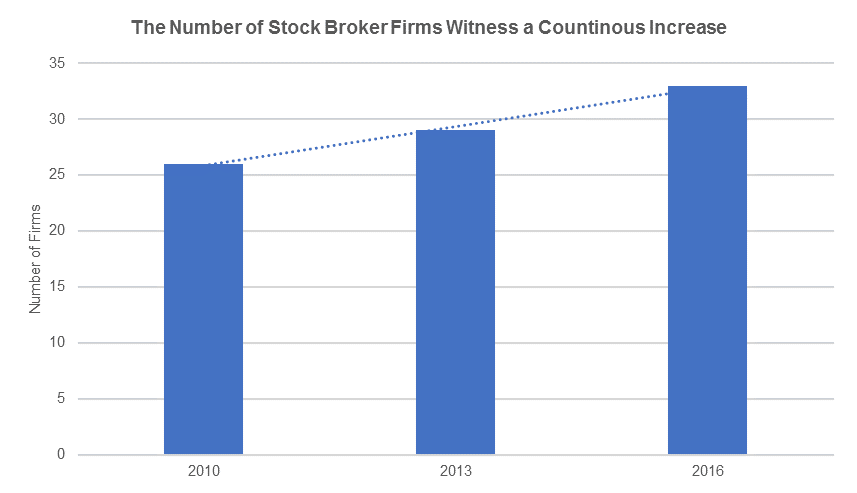

Steady Increase in the Number of Licensed Stock Brokers Stockbrokers and investment managers are major players in the stock exchange as they provide greater access and services to investors which is key to increasing market participation. As such, the Colombo stock exchange market has seen a high growth of 26.9% (26 to 33 firms) and 35.7% (18 to 28 managers) in licensed stock brokers and investment managers during 2010-16 respectively, driving public offer of securities in the primary and secondary market.

Source: Colombo Stock Exchange (CSE), Securities Exchange Commission (SEC) Sri Lanka |

Appendix

|

Appendix A – Key Statistical Indicators

Source: Central Bank of Sri Lanka, World Bank

Appendix B – Political and Legal Overview

Source: PwC, Ernst and Young (EY), UZABASE |