Thailand Aims to Use the New Investments Promotion Strategy to Overcome the Middle Income Trap

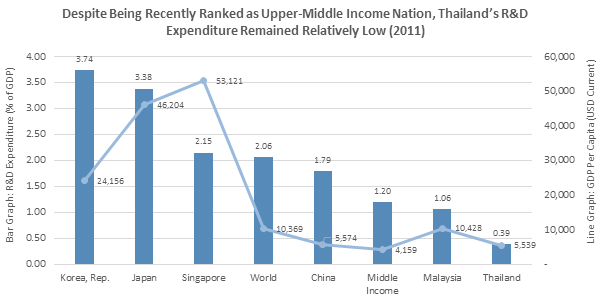

On the 1st of January 2015, the seven-year investment promotion strategy (2015-2021) (7YIPS) came into effect in Thailand after being approved by the Board of Investment (BOI). 7YIPS is intended to help overcome the middle income trap by tapping foreign direct investments (FDI) and technological know-how, promoting new value-added sectors, endorsing investments in R&D, and decentralising investments into lower income regions.

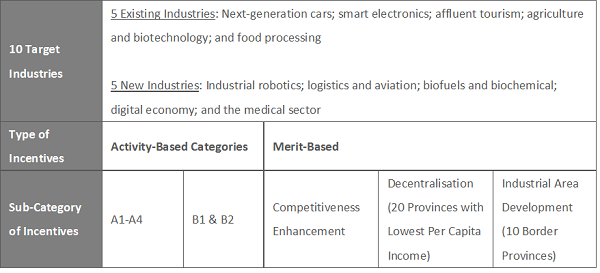

In order to achieve this goal, modifications were made to the previous strategy on three aspects of the investment incentives: the scope, the geography, and the basis of incentives. In the 7YIPS, the government has chosen 10 target industries for investment promotion and has clearly defined business activities into categories A1-A4, B1 and B2, with business activities in category A1 receiving the most attractive incentives due to their knowledge-oriented business activities. Secondly, the new strategy has abolished incentives under the zoning scheme, which classified geographic incentives only into three zones based on the distance from central Thailand. Under the business zoning scheme, higher incentives were given to investments further away from the central area. Nevertheless, in the 7YIPS, more structure was given to geographic incentives by forming regional business clusters to specialise in specified industries. Lastly, apart from activity-based incentives, merit-based incentives were introduced in order to encourage R&D and to direct investments into designated geographic locations.

Thailand Caught in the Middle-Income Trap for Decades

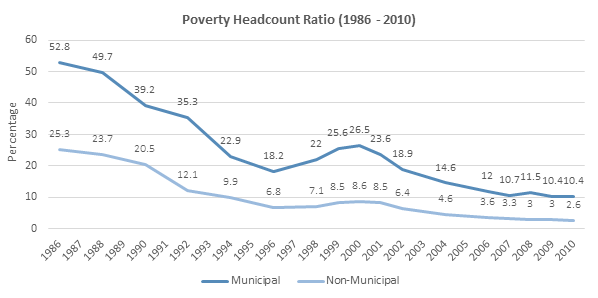

Thailand is believed to have fallen into the middle-income trap from around 1994-1995, after years of continuous drops in the poverty headcount ratio. Since 1986, poverty in the country has declined significantly from 67% to 11% in 2014 alongside the increase in income. However, Thailand is considered to be stuck in the middle-income trap where a country is successful in improving its economy from being a low-income to a middle-income country, but fails to progress into becoming an advanced economy and has a low prospect of moving up the value chain due to a lack of technological development.

For many decades, Thailand has built its economy on cheap labour, exploitation of natural resources, borrowed technology, and reliance on export markets. While this economic model has helped Thailand out of the low-end of the income spectrum, it has also led to the degradation of the environment, caused income disparity within the country, and has yet to push Thailand up into the high-income segment.

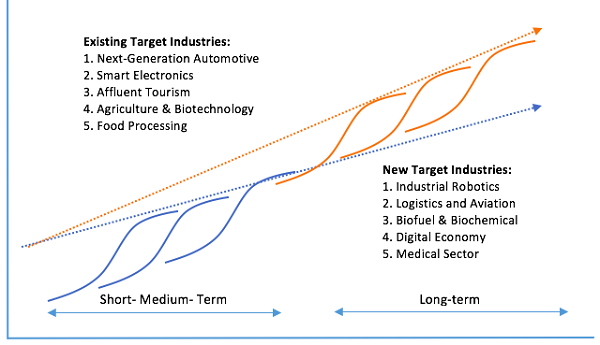

New Target Industries Expected to Foster New S-Curve

The government estimated that, in the medium-term, the development of the existing five targeted industries would create the first S-Curve and increase the combined revenue of these industries by 70%, while the development of new industries would increase it by a further 30%. However, in the long-term, the government believes that investments and development of the new targeted industries would enable Thailand to build a technological edge and diversify its competitive advantages, leading to the new S-Curve, which could enhance Thailand’s economy sustainably.

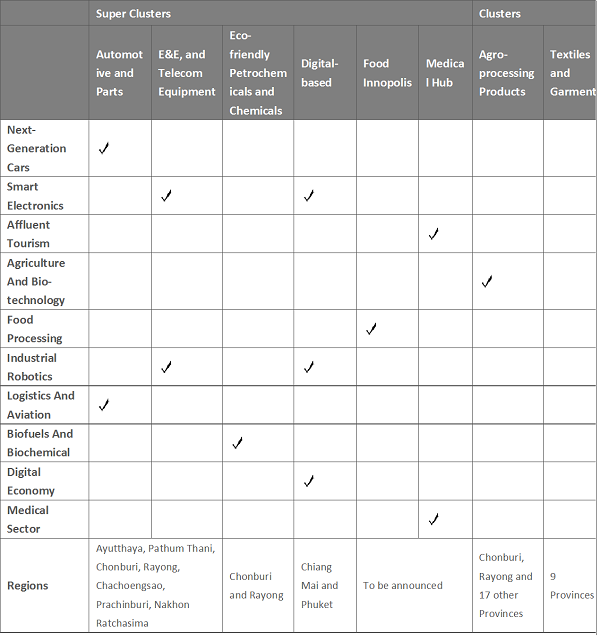

To support the 7YIPS and encourage investments in the 10 target industries, eight business clusters were formed, six of which were categorised as super clusters, while the other two are normal clusters. Business clusters also promote the concentration of interconnected businesses, in order to enhance the level of vertical and horizontal cooperation among enterprises and strengthen the industrial value chain.

Apart from agriculture and biotechnology, all of the super clusters are associated with at least one of the target industries. There are a total of 29 provinces involved in the business clusters. The clusters with the highest number of associated provinces are agro-processing products, textiles and garments, automotive and parts, and E&E and telecommunication equipment. Agro-processing products and textiles and garments cover the most provinces as they are two of the most traditional industries fundamental to Thailand’s economy.Provinces with the most overlaps between clusters are Chonburi and Rayong, which are present in four different clusters. Chonburi is home to Thailand’s largest and primary seaport and has the widest motorway connection to Bangkok among other provinces outside of the Bangkok Metropolitan Area, making it a logistically strategic province to be located in. Chonburi is also a tourist destination, famous for its beaches; Pattaya City attracts not only tourists but also expats and migrants. Meanwhile, Rayong is Chonburi’s neighbouring province, allowing it to easily access Chonburi’s logistics facilities.

Activity-Based Incentives Prioritise Knowledge-Based Activities

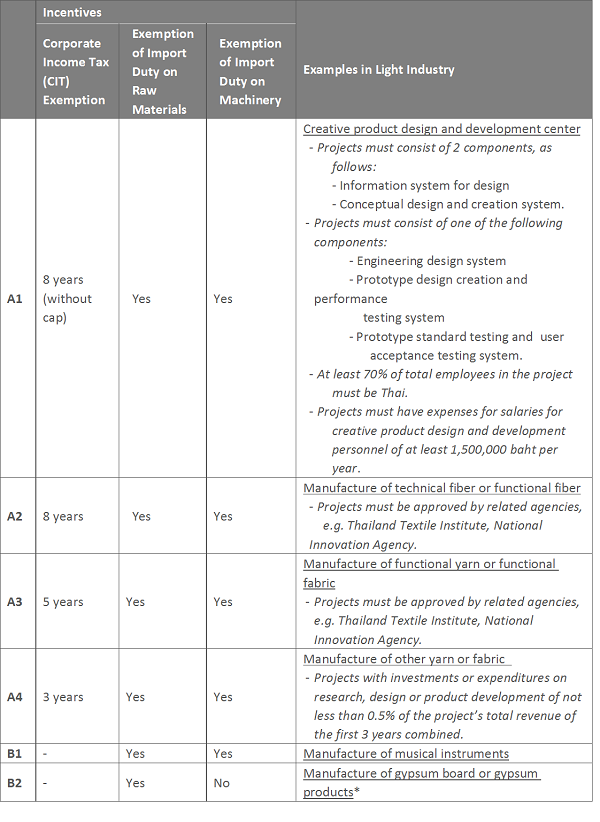

Activity- and merit-based incentives make up the foundation of incentives for investing in business clusters. Activity-based incentives serve to promote investments in businesses that enhance the country’s knowledge, technology, and infrastructure, in a prioritised manner depending mainly on the level of technology utilised. As such, investments in A1 business activities, which require the highest knowledge and technology, receive the most incentives.

Regarding tax-incentives, depending on the initial investment value, the cap for CIT exemption is determined for investments in all business activities categories apart from A1. The specified value of the CIT exemption could be utilised and deducted from the company’s annual CIT expenses over the number of years acquired for CIT exemption, until either the cap is reached or the CIT exemption duration is up. However, investments in the A1 business category would receive an unlimited amount of CIT exemption for eight years, making it the most attractive business activities category for investment.

Investors are eligible for activity-based incentives regardless of investment location and industries, as long as they fall into one of the business activity categories, which cover over 200 activities. Investments in business clusters may be granted up to a maximum of 8 years of CIT exemption as shown in table 3.

Merit-Based Incentives are Used to Encourage R&D and to Channel Investments to Designated Regions

There are three types of merit-based incentives: competitive enhancement, decentralisation, and industrial area development. Merits on competitive enhancement serve to encourage knowledge-based investments and investments in R&D, which are fundamental for breaking out of the middle income trap. Depending on the percentage of such investments of the total expenditure, investors may be granted up to three additional years of CIT exemption on top of what is granted from activity-based incentives.

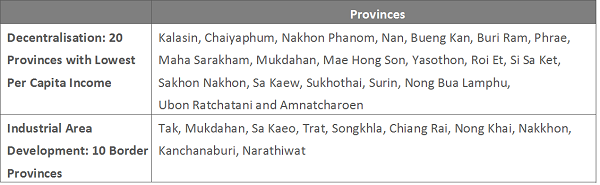

Investments in business clusters are comparable to that of investments under the decentralisation and industrial area development scheme, as they are all geographic merit-based. However, the incentives for investing in business clusters surpass that of the other two schemes, as they directly support the 10 target industries for sustainable economic growth. Merits for decentralisation and industrial area development aim to facilitate cross-border trade, the dispersing of income, and boost the local economy of lower income provinces. To encourage investments in these regions, investments in the 20 provinces with the lowest per capita income could increase CIT exemption up to three additional years, and up to one year for investments in 10 chosen border provinces. There are three overlapping provinces between these two incentive schemes, which are Nakhon Phanom, Mukdahan, and Sa Kaeo. On the other hand, there are four overlapping provinces between the business cluster scheme and the other two geographical schemes (Kanchanaburi, Chiang Rai, Trad, and Songkhla), all of which are border provinces, strategic for trade and cheaper labour from neighbouring countries.

To advocate investments in super clusters (refer to table 2), investors are eligible for incentives from both the BOI and the Ministry of Finance (MoF). Depending on the business activity, investors may be granted up to eight years of CIT exemption with an additional 5 years of 50% CIT exemption from the BOI. Under normal circumstances, investors are only eligible to a maximum combined CIT exemption of eight years under the 7YIPS, irrespective of business activity, value of R&D, and investment location. However, as a means of encouraging investments in super clusters, the MoF may also grant additional years of CIT exemption, of up to 15 years, and personal income tax exemption for international specialists to work in the clusters. In terms of non-tax incentives, the BOI would consider granting permanent residence to leading specialists and permission for foreigners to own land to implement the promoted activities.

Investments in Renewable Energy Take the Lead in 2015

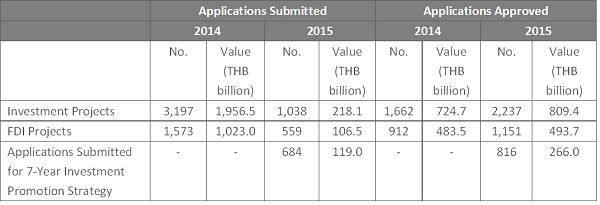

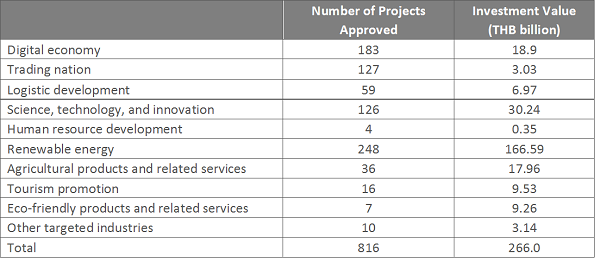

The announcement of the 7YIPS in 2014 has led to an influx of investment project applications around the end of 2014, which impacted the number of applications in 2015. By the end of 2015, 684 applications were submitted for incentives under the 7YIPS programme, which represented 65.9% of the total number of applications, and 54.6% of the total investment value. Out of the applications submitted, over 100% (816 applications) were approved for incentives, as some projects were granted incentives even without filing applications. This demonstrates the keenness of the Thai government in endorsing projects in target industries. Moreover, the total value of approved projects under the 7YIPS constituted 32.9% of the total approved projects.

Among the approved applicants for incentives from the 7YIPS programme, investment projects in renewable energy received the highest number of approvals and had the highest investment value. From 816 projects approved for incentives, up to 30% were projects in renewable energy, which accounted for 62.6% of the total investment value. This investment category falls under the biofuels and biochemical target industry and corresponds to the eco-friendly petrochemicals and chemicals business cluster, designated at the Chonburi and Rayong provinces. Following renewable energy, investments in science, technology and innovation had the second highest investment value, which contributed 11.4% to the total investment value under the 7YIPS scheme. Investments in this category cover all 10 of the target industries, and thus could be located in multiple clusters.

Will Thailand Succeed in Escaping the Trap?

Through the 7YIPS, Thailand is trying to push itself up the value chain and out of the middle income trap, but it is not the only country aiming to do so. With the recent implementation of the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) in 2015, competition to become more advanced is extremely high in Southeast Asia. Malaysia is one of the nations that has also been stuck in the middle-income trap for over a decade. Moreover, for as long as Thailand has, Malaysia too has been trying to fight its way out. In 2014, Malaysia announced that it plans to achieve the high-income status as defined by World Bank by 2020.

Even though some would consider exiting the middle-income range to be an “economic miracle,” a few Asian nations have been successful in escaping the trap, such as Taiwan, Hong Kong, Japan, South Korea, and Singapore. In the 1950s, Thailand’s economic development was comparable to that of South Korea. However, South Korea had chosen to focus more on establishing its own internationally competitive industries to reduce reliance on exports. By the 1990s, South Korea became a high income nation with some of its brands, such as Samsung, LG, and Hyundai being large players in the global arena in their respective industries. Therefore, there may be some hope left for Thailand in the coming years.

While the 7YIPS may be one of the keys for Thailand to become an advanced economy, there are other crucial aspects that should not be overlooked. One factor that contributed to South Korea’s success in escaping the middle-income trap was said to be its human capital, which was a result of its high-quality education system. Meanwhile, Malaysia’s failure to progress could be partially attributed to the country’s political instability.

Remodeling economic policies is a positive step forward for Thailand. However, it is far from being the only measure that the country must undertake. In addition to economic policy, the country must look toward reform in other areas in order to build a solid foundation for sustainable economic growth and thus break out of its longstanding predicament as a middle-income nation.