China Country Report: Navigating Through Transition

Executive Summary

World’s Second-Largest Economy Undergoing a Period of Transition

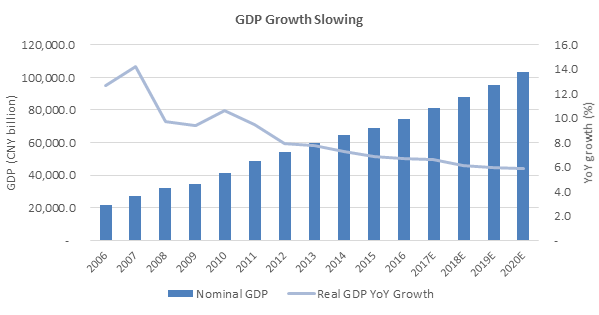

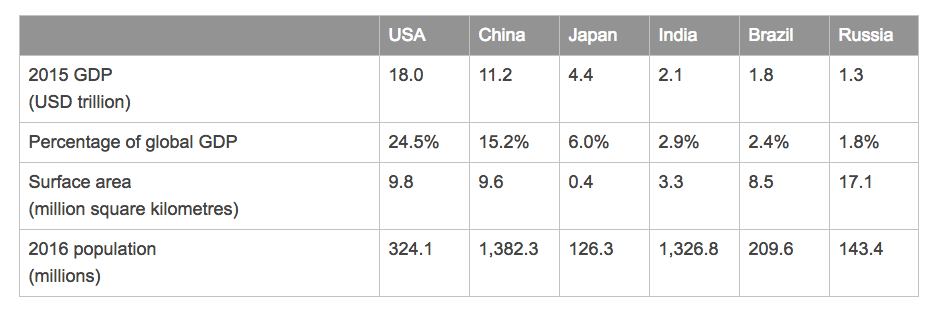

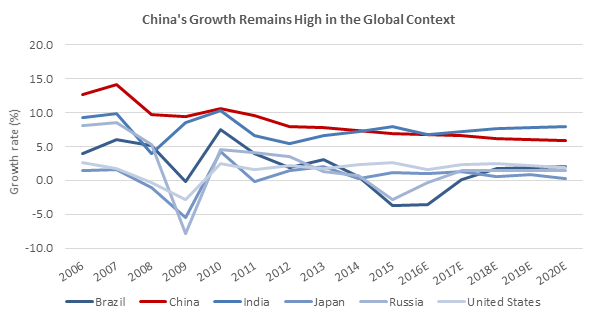

The People’s Republic of China (PRC)(*1), a middle-income country according to the World Bank, has seen rapid growth since implementing Economic Reforms programme in 1978. It is now the second-largest economy in the world, accounting for 15.2% of global GDP in 2015, preceded only by the USA (24.5%). China is undergoing multiple transitions as it attempts to increase the contribution of the tertiary sector and shift towards a more consumption-driven economy from a capital investment-oriented one. Although China’s GDP growth has been slowing over the past few years, the IMF estimates it to be around 5.9% in 2020, still higher than the estimates for the USA (1.2%) and Japan (2.8%).

Leading Player in International Trade Seeks to Enhance Comparative Advantage through Technological Advancement

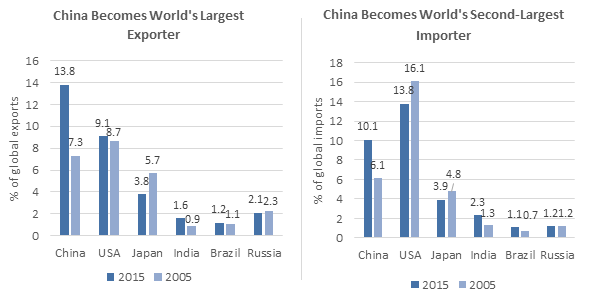

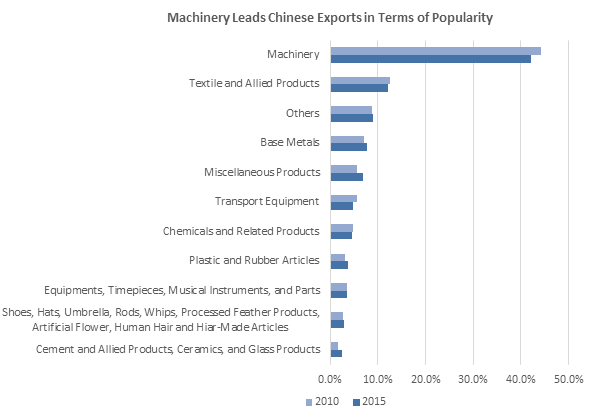

The PRC accounted for 13.8% of global trade in 2015. As a net exporter, it has traditionally traded low value-added products (benefitting from relatively low wage costs) for high value-added ones; this has compensated for a lack of advanced technological capability domestically. China currently attaches considerable importance to the development of high-technology industries and the advancement of R&D capability. As an extremely policy-driven country, the government plays an important role in guiding the expansion of these industries by formulating strategies. One example is its Made in China 2025 strategy, which assigns targets for related industries to achieve by 2025 in terms of production volume, technological requirement, sufficiency rate, etc. Regular five-year plans also draw a framework for the development of other industries.

Walking the Policy Tightrope; Expansionary Monetary and Fiscal Policy Necessary to Stimulate Growth while Maintaining Inflation amidst Depreciation of Renminbi

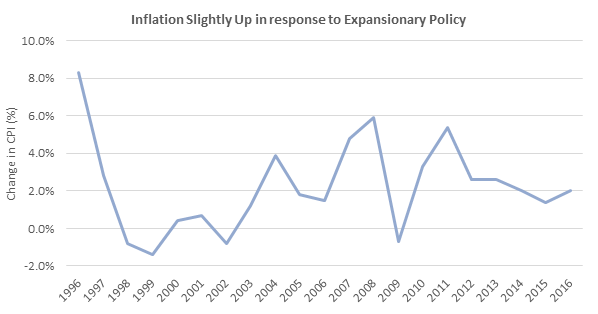

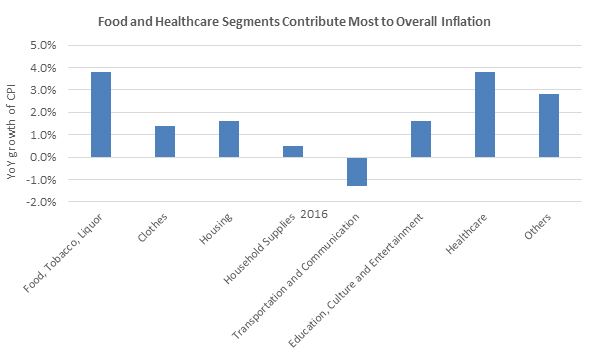

The People’s Bank of China implemented moderately expansionary monetary policy in 2016 to boost economic growth. The authority reduced the deposit reserve rate and the interest rate and also issued repos and other instruments in order to ensure sufficient liquidity in the money market. In response, the inflation rate rose a slight 0.6 percentage points YoY to 2.0% in 2016. The government also implemented expansionary fiscal policy, reducing tax revenues and increasing government expenditure. In particular, it comprehensively replaced business tax with value-added tax in order to eliminate tax duplication and to raise expenditure to improve people’s livelihoods, e.g. in healthcare and employment. This combination of monetary and fiscal policy has contributed to the depreciation of Chinese renminbi, adding cost-push inflationary pressures.

Demographic Dividend Fades as the World’s Largest Population Faces Rapid Ageing and Gender Imbalance

Although China has the world’s largest population, it is facing an increasingly significant ageing problem that will gradually take away the country’s demographic dividend and lead to an insufficient workforce. To manage this problem, the government replaced its one-child policy with a two-child policy, aiming to boost its low birth rate (around 1.2%) and to lower its high dependency rate (around 39%). China’s gender disparity currently stands at a female-male ratio at birth of 100.0:116.0 (India’s is 100.0:110.9). Although the figure is improving under stricter government regulation against sex identification of foetuses and gender-based terminations, concern remains, given a longstanding preference for male offspring, especially among older generations and rural residents.

Financial Market Liberalisation Efforts Still a Work in Progress; the World’s Second-Largest Stock Market Continues to be Dominated by Retail Investors Frequently Led by Herd Mentality

As the world’s second-largest stock market in terms of market capitalisation (approximately USD 7.6 trillion as of 2016), China’s stock market is dominated by retail investors, while institutional investors are few; this results in a less rational investing environment. The market is greatly influenced by policy, but is largely independent from GDP growth prospects. The two major stock exchanges, the Shanghai Stock Exchange (SSE) and the Shenzhen Stock Exchange (SZSE), have both underperformed foreign peers despite GDP growth. The Chinese renminbi’s inclusion in the SDR basket marks China’s reform progress and international standing, and also fosters further liberalisation of the financial market, including liberalisation of the interest rate and the promotion of capital convertibility and liquidity.

Bond Market an Important Source of Government and Corporate Financing; Downgrade by Moody’s to A1 from Aa3 Remains Questionable

The bond market serves as a source of financing for infrastructure construction. The outstanding bond value grew at a CAGR of 13.8% to CNY 43.7 trillion (≈USD 6.6 trillion(*2)) during 2010-16. Further, types of bonds are proliferating, offering more options for local governments and corporates to finance their operations. Moody’s downgraded China’s credit rating to Aa3 from A1 in May 2017, as it anticipates erosion in China’s economy on the back of decelerating growth and mounting debt. However, the downgrade is questionable, as the country’s GDP growth rate is estimated to remain at a comparatively high level (5.9% in 2020, as per the IMF). Moreover, China has restricted local government financing, and local government debt and central government debt together came in at 36.7% of GDP in 2016, lower than the debt-to-GDP ratios of Japan (234%, 2015) and the USA (126%, 2015).

Country Overview

Creation of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 Ended an Extended Period of Foreign Rule; Economic Reform Initiated in 1978 Ushered in a Period of Rapid Development

Although the World Bank continues to classify it as a middle-income country, China became the second-largest economy in the world in 2010, after the USA and ahead of Japan. According to the latest UN data, China accounted for 15.2% of global GDP and 13.8% of global exports in 2015, carrying more weight in the global economy than before. Moreover, China has gained more influence in the world since being appointed one of the five permanent members of the UN Security Council in 1971.

China Ranked Second in Global GDP, Outperforming Japan and the Rest of BRIC

Source: National Bureau of Statistics

Note: GDP for 2016 is unadjusted data, as adjusted data is unavailable

China’s civilisation dates back more than 4,000 years to the Xia dynasty (2070 B.C.), its first dynasty. Under imperial rule by numerous dynasties that followed, the country saw both prosperity and decline. China was never a unified kingdom until the Qin dynasty (221–207 B.C.). Later, under the Tang dynasty (618–907 B.C.), it experienced its golden age during which its economics and culture developed. During the late Qing dynasty (1644–1911), the government adopted a policy of isolationism, and the people became largely self-sufficient. The two Opium Wars (1839–42 and 1856–60) involving Britain and France as well as the Eight-Nation Alliance(*3) in 1900 reduced China to a semi-colonial and semi-feudal nation plagued by poverty, social instability, and war. The foreign powers gained commercial privileges and territorial concessions through their victories. Five trading ports in Shanghai, Ningbo, Xiamen, Fuzhou, and Guangzhou were forced to open, and China lost Hong Kong to Britain in the Opium Wars (Hong Kong was returned in 1997). The People’s Republic of China (PRC) was formally established by the Communists on 1 October 1949 after World War II (1939–45) and the Chinese Civil War (1929–49), marking the beginning of the revolution and the birth of socialism in China.

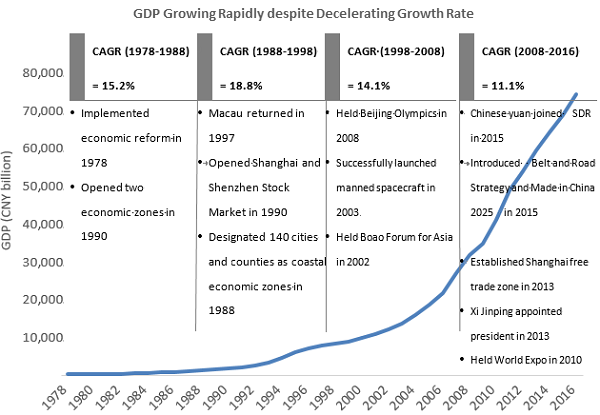

The economic reform introduced in 1978 initiated a new stage of development. The country’s GDP grew fast at a CAGR of 13.5% to CNY 74.4 trillion (≈USD 11.2 trillion) in 2016 from CNY 11.1 trillion (≈USD 1.3 trillion) in 2001, when China joined the World Trade Organisation (WTO). During a period of rapid reform, China strengthened its partnership with foreign countries and attracted significant foreign capital. Meanwhile, low labour and manufacturing costs have made China the factory of the world and a major exporter of goods. However, as the average annual wage of urban workers (i.e. labour costs) increased at a CAGR of 14.2% to CNY 62,029.0 (≈USD 9,959.9) in 2015 from CNY 1,332.0 (≈USD 385.8) in 1986, many foreign companies are reluctant to establish new manufacturing factories in China, and some have even relocated their factories to other countries, e.g. Vietnam. Therefore, China is focusing aggressively on research and development (R&D) for manufacturing and high-tech industries in order to compete on technology instead of on labour costs.

|

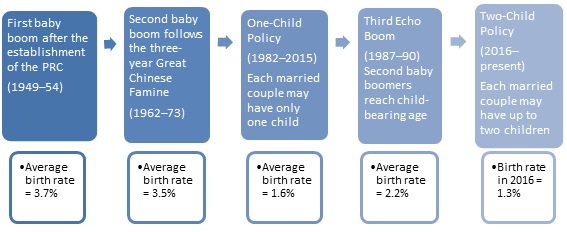

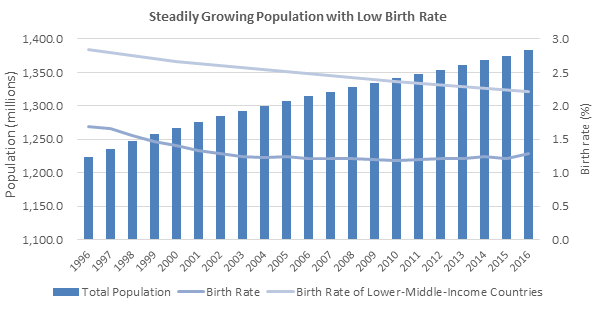

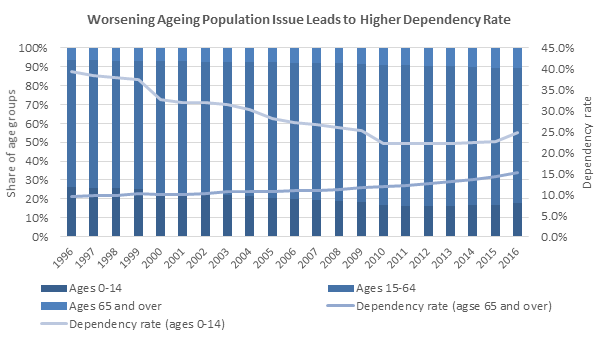

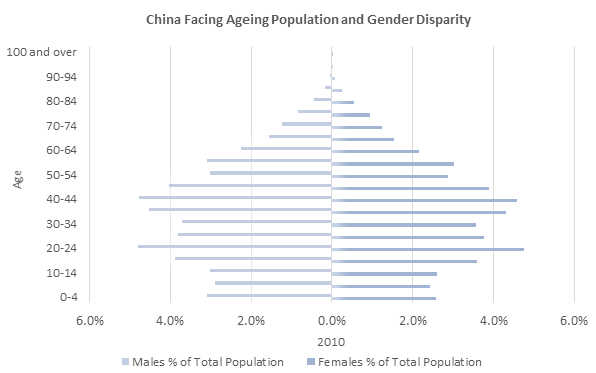

China’s Population Remains the World’s Largest; a Low Birth Rate, an Ageing Population, and Gender Disparity Are the Main Demographic Concerns As of 2016, China is the most populous nation in the world, with a population of nearly 1.4 billion (around 19% of the world population), beating India. However, its birth rate has flattened at around 1.2% over the years, after having decreased to 1.2% in 2003 from 2.2% in 1982, which is lower than the average global birth rate (2.0%) and the average birth rate of lower-middle-income countries(*4) (2.4%) for 2010–15. China’s low birth rate as well as the rate’s decrease are attributable mainly to its one-child policy. The policy was officially implemented in 1982, and it mandated that each married couple have only one child. The policy was introduced to prevent a population explosion and a shortage of food and other resources. Although the policy succeeded in controlling population growth, it also led to the increasingly severe problem of an ageing population. The share of China’s population aged 65 and over increased 4.5 percentage points to 10.9% in 2016 from 6.4% in 1996, and the State Information Centre expects the figure to reach 18.2% by 2030. Consequently, dependency of the elderly (ages 65 and over) has been increasing continuously to 15.2% in 2016 from 9.5% in 1996, while that of the young (ages 0-14) has stabilised at around 22% during 2010–15, after having declined from 39.3% in 1996 due to the one-child policy. The total dependency rate (around 39%) highlighted the working population’s heavy burden of providing for the young and the aged. In response, the Chinese government replaced the one-child policy with a universal two-child policy on 1 January 2016, in order to mitigate the problem of the ageing population and to expand the future working population. In 2016, the birth rate improved by 0.09 percentage points in response to the new policy. However, the effect of easing birth control tends to be limited, as many couples are concerned about the quality of public infrastructure (e.g. kindergartens and hospitals) and the family’s economic situation, especially couples in first-tier and second-tier cities, where financial pressures are stronger. According to the National Bureau of Statistics’ 1% sampling survey, the female-male ratio in China was 100.0:105.0 in 2015, compared with 100.0:105.2 in 2010, according to the latest census. However, the UN claimed that China’s female-male ratio at birth was 100.0:116.0 in 2015, even lower than that of India’s: 100.0:110.9. In China, the preference for male offspring stretches back centuries to when households favoured sons in order to support a stronger work force. Today, the preference for sons has eased, as women increasingly engage in work and gain higher social status than before. Nevertheless, the phenomenon prevails in rural areas and among older generations. Typically, those two demographics regard sons as inheritors; they believe that a son will provide for the aged and that daughters will leave home upon marriage to join another family. Many couples in these demographics terminate pregnancies that show female foetuses. The resultant gender disparity could lead to a series of negative consequences, e.g. gender discrimination in the workplace. China officially prohibited sex identification of foetuses and gender-based terminations starting 2016. This could go some way towards improving the gender disparity problem in the future. China’s Historical Baby Booms and the Evolution of Its Birth-Control Policies

Source: National Bureau of Statistics

Sources: National Bureau of Statistics; UN

Source: National Bureau of Statistics

Note: 2016 data for ages 0-14 is the population for ages 0-15, as data for ages 0-14 is unavailable

Source: National Bureau of Statistics, 2010 Population Census (latest) |

|

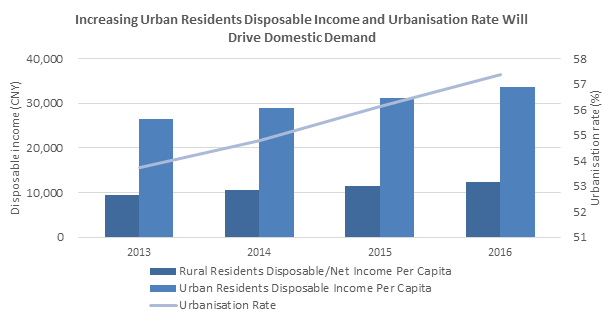

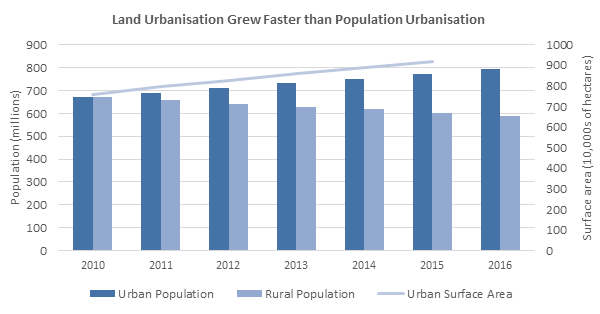

Burgeoning Urbanisation Widens Regional Income Disparities and Leads to Excessive Land Confiscation The wealth gap between urban and rural residents is significant in China. In 2016, the annual disposable income of urban residents was CNY 33,616.0 (≈USD 5,060.5) compared with CNY 12,363.0 (≈USD 1,861.1) for rural residents. As such, an increasing urban population(*5) could drive up the purchasing power of Chinese people and thereby stimulate domestic demand. Due to government efforts to foster urbanisation, the urban population in China increased to 793.0 million (57.3% of total population) in 2016 from 57.7 million (10.6%) in 1949. China has made significant progress in urbanisation over the decades, and has exceeded the average urbanisation rate of middle-income countries (50.8% as of 2015). But it continues to record a lower level of urbanisation than other developed countries such as Japan (93.5% as of 2015) and the USA (81.6% as of 2015). Another notable characteristic is the significant urbanisation gap between the eastern (62.2% as of 2016) and western regions (44.8% as of 2016). China is a vast country with a diverse landform and abundant but unevenly distributed natural resources. In 2015, the eastern regions, comprising mainly plains and hills, contributed 54.1% of the country’s total GDP, while the western regions have lagged at 21.0%, as the mountains, highlands, and basins make them less favourable for living and economic activity. Moreover, the western regions have richer natural resource reserves than do the eastern regions, including in terms of oil, natural gas, and coal. In 2000, China implemented a ‘Western Development Strategy’ in order to boost its regional economies, increase urbanisation, and improve public infrastructure such as railways and highways. In 2016, the western regions reported GDP growth of 8.6%, higher than the nation’s overall GDP growth of 6.7%. The National Development and Reform Commission of the PRC predicts the western regions’ urbanisation rate to exceed 54% by 2020. Nevertheless, the Chinese government’s aggressive promotion of urbanisation raises some concern, e.g. about the gap between the availability of urban surface area and growth in urban population. Over 2010–15, urban surface area grew at a CAGR of 3.8% from 7.6 million hectares to 9.2 million hectares, while the urban population grew only at a CAGR of 2.9% from 669.8 million to 771.2 million. Although local governments confiscated rural land to build new cities and towns, the smaller-than-expected flow of residents from rural to urban areas has turned some new cities into “ghost cities”. These have resulted from insufficient public infrastructure (e.g. education, healthcare, and transportation) in these new cities and towns and their failure to provide livelihood guarantees (e.g. housing and employment). Whether the situation can be improved through deceleration of urbanisation growth remains to be seen.

Source: National Bureau of Statistics

Sources: National Bureau of Statistics; Ministry of Land and Resources of the PRC |

|

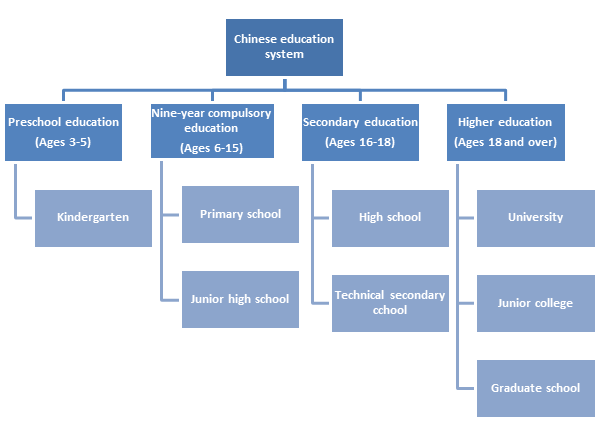

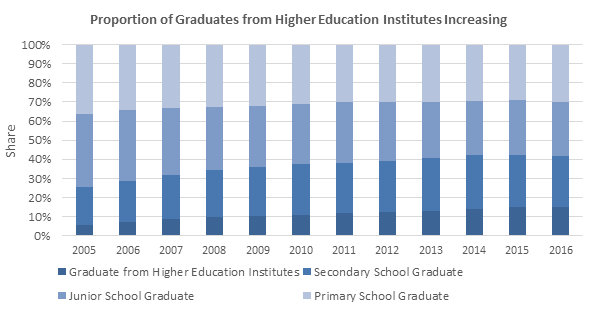

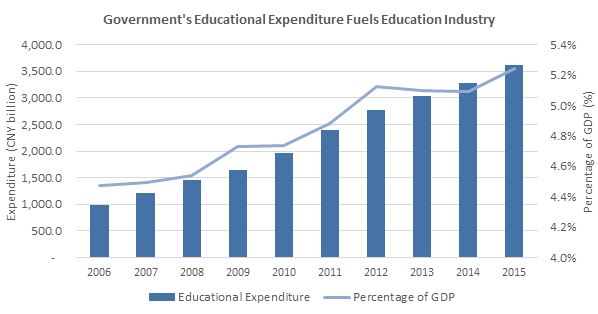

Government Investing Heavily in Education, with Significant Private-Sector Involvement; Literacy on an Uptrend, While Participation in Higher Education Is Improving According to UNESCO, China’s adult literacy rate increased to 94.3% in 2010 from 77.8% in 1990 and is estimated to reach 95.5% in 2015. Under its Compulsory Education Law promulgated in 1986, China has been implementing a policy of nine years of compulsory education (five years of primary school education and four years of junior high school education, or six years of primary school education and three years of junior high school education) in order to eliminate illiteracy among youth and adults. As of 2016, the retention rate of students enrolled in the nine-year compulsory education program peaked at 93.4%. Although further schooling including secondary education and higher education is entirely up to the discretion of individuals or families, an increasing number of students are involved in further schooling to pursue higher degrees. In 2016, the proportion of graduates from higher education institutes over graduates from all schools increased to 15.2% from 5.9% in 2005; meanwhile, the proportion of graduates from secondary education increased to 26.4% from 19.5% over the same period. Although private capital is also welcomed in the education industry, most of the existing institutions, especially the top-ranking institutions, are publicly funded. China is investing heavily in education, with expenditure increasing at a CAGR of 15.6% during 2006–15, reaching CNY 3.6 trillion (≈USD 0.6 trillion) in 2015. In addition, the Chinese State Council replaced the 985 and 211 Projects(*6) with the Coordinate Development of World-class Universities and First-class Disciplines Construction Overall Plan in October 2015. This was in order to foster world-class universities with strength in teaching and scientific research. Chinese officials have announced intentions to foster 16 world-class universities across the country by 2030. Talent harnessed in these institutions will enhance the country’s overall R&D capacity — a critical premise for the development of high-technology industries. Segmentation of the Chinese Education System

Source: by UZABASE

Unit: million people

Source: National Bureau of Statistics

Sources: Ministry of Education; National Bureau of Statistics |

|

Similar Cultural Traits Nationwide, with Interesting Differences between Northern and Southern China China can be divided geographically into two parts — northern and southern — along the Qin Mountains-Huai River Line. North-south differences in language/dialect and culture have fostered strong regional stereotypes among the Chinese people. Mandarin is the official national language; however, northern Chinese usually have a northern accent with the r-colouring, while southern Chinese do not. Additionally, six out of the seven dialect families originate from southern China, and they can be difficult for others to understand. In addition to the general traits listed in the following table, Chinese culture too presents some differences between the northern and southern parts. Northern Chinese tend to practice explicit and straightforward communication, and they rely heavily on relationships when doing business. In contrast, Southern Chinese are more implicit and euphemistic in communicating, and they are good at strict budgeting and value deal efficiency. On a related note, northern China is relatively more bureaucratic owing to the capital, while southern China is more commercial and more active in business. In 2016, the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Metropolitan Region contributed around 10% of total GDP; in comparison, the Yangtze River Delta — comprising Shanghai, Zhejiang, and Jiangsu — contributed 16.5%, and the Pearl River Delta in Guangzhou contributed 9.1% (2015). Key Cultural Traits Shared Nationwide

Source: by UZABASE based on Geert-Hofstede |

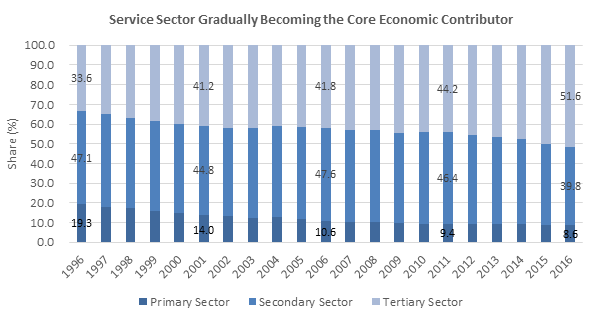

Economic OverviewGrowth Rate Down; Contribution from Services Sector Up China was ranked the second-largest economy in the world, with a GDP of CNY 74.4 trillion (≈USD 11.2 trillion) in 2016. Although China’s GDP grew at an impressive CAGR of 13.0% during 2006-16, its YoY growth rate has been declining since 2011. International organisations including the UN and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimate that China’s growth rate will continue to fall in the coming years. That said, China’s estimated growth rate remains high at around 5.9% for 2020F, second only to that of India (8.2%) and ahead of the USA’s, Japan’s, and those of the rest of BRIC. On the other hand, owing to China’s large population, its GDP per capita stood at CNY 53,980.0 (≈USD 8,126.0) in 2016, comparatively lower than the USA’s (USD 56,116.7 in 2015) and Japan’s (USD 34,523.7). As a large country naturally rich in agricultural resources, China has a long history of farming. Before the Economic Reform of 1978, China focused more on the development of the primary sector (agricultural, forestry and fishing, and mining and quarrying) and the secondary sector (industries), perceiving the limited economic contribution of the tertiary sector (services) due to non-material productivity. It was not until 1992 that China officially decided to comprehensively develop its tertiary sector. The primary sector’s contribution to the economy more than halved to 8.6% in 2016 from 19.3% in 1996, while the secondary sector’s declined 7.3 percentage points to 39.8% from 47.1% during the same period. Meanwhile, the contribution from the tertiary sector rose to 51.6% from 33.6%; this implies a shift to a more services-sector oriented economy.

Source: National Bureau of Statistics, 2017-20 estimation sourced from the IMF

Sources: National Bureau of Statistics; IMF

Note: 2016 data for India and China denotes realised growth

Source: National Bureau of Statistics |

|

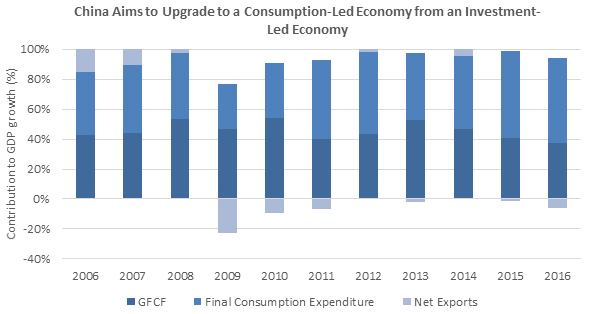

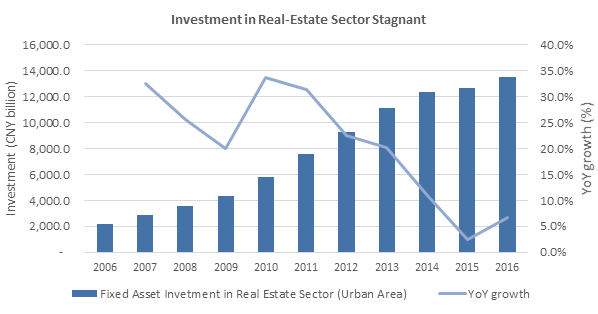

Transition to Consumption-Led Economy Underway; Real-Estate Sector Serves as GDP Growth Pillar, but Investment Is Slowing Over the past few years, China’s GDP growth was driven by capital investment. As of 2016, the country’s gross fixed capital formation (GFCF) totalled CNY 31.4 trillion (≈USD 4.7 trillion), accounting for 42.2% of its GDP. During 2013–16, the share of GFCF in GDP dropped 13.1 percentage points to 42.2% from 55.3%, while that of final consumption expenditure rose 17.6 percentage points to 64.6% from 47.0%. The widening difference between the two factors indicates China’s effort to upgrade to a consumption-led economy from an investment-led one.In 2016, investment in fixed assets (urban area) reached CNY 59.7 trillion (≈USD 9.0 trillion, around 80.2% of GDP), of which investment in the real-estate sector amounted to CNY 13.5 trillion (≈USD 2.0 trillion, around 18.2% of GDP), making the real-estate sector one of China’s growth pillars. Moreover, the upstream and downstream industries of the real-estate sector, including the construction, materials, machines, furnishing, and household appliances industries, all benefit from the rapid expansion of the real-estate sector and contribute collectively to GDP growth. However, the real-estate sector is now facing stagnation, as investment increased only at a CAGR of 4.6% during 2014–16, compared with a CAGR of 21.3% during 2011–13. Although the figure rebounded in 2016 on higher land prices in tier-2 and tier-3 cities, we expect investment in the sector to moderate. The slowdown results from the market’s entry into a stage of destocking alongside supply-side reforms(*7) , with commercial housing inventory reaching 695.4 million square metres as of end-2016. In addition, many local governments in tier-1 and tier-2 cities have restricted their housing purchases by raising the down payment ratio in order to stop irrational price increases on the back of speculation and to prevent the housing bubble from bursting.

Source: National Bureau of Statistics

Source: National Bureau of Statistics |

|

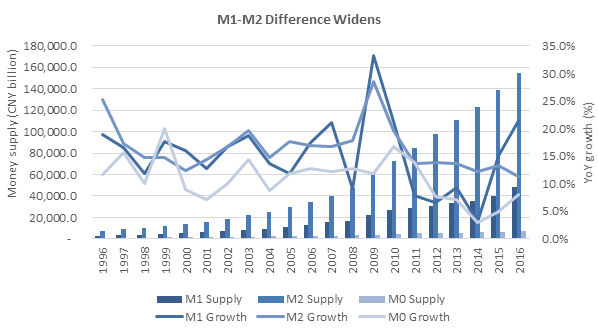

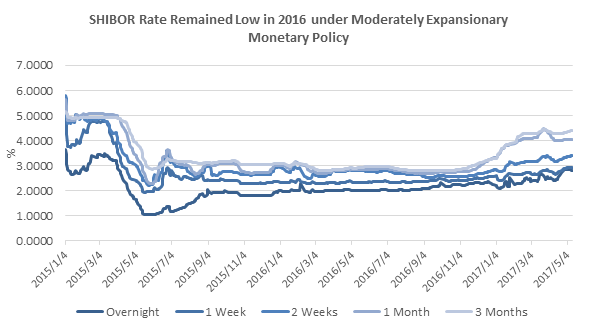

Moderately Expansionary Monetary Policy to Maintain Liquidity and Control Inflation The People’s Bank of China (PBC), China’s central bank, is empowered to formulate and implement monetary policy and to regulate financial institutions. The formal objective of China’s monetary policy is to maintain the stability of the currency value and thereby to promote economic growth. China has pursued a moderate monetary policy in recent years, with policy slightly expansionary or restrictive in character, according to market conditions. In 2016, the PBC implemented a moderately expansionary monetary policy, and the broad money (M2) supply increased 10.3% YoY to CNY 155.0 trillion (≈USD 23.3 trillion). In March 2016, the PBC reduced the deposit reserve rate by 0.5 percentage points after lowering the rate five times in 2015 to ensure adequate liquidity for financial institutions. The SHIBOR overnight rate, as an indicator of the interest rate, stabilised at around 2% through 2016; this was favourable for investment and consumption. In addition, the PBC conducted a 7-day repo of CNY 17.9 trillion (≈USD 2.7 trillion) and applied a 14-day repo (CNY 3.9 trillion, ≈USD 0.6) and a 28-day repo (CNY 3.0 trillion, ≈USD 0.4 trillion) in the open market. Other recently introduced instruments include a standing lending facility (SLF) and a medium-term lending facility (MLF) to cater to financial institutions’ temporary and seasonal liquidity needs. It is noteworthy that the scissors difference of the M1-M2 growth rate turned positive from negative in 2015 and quickly widened to 10.1% in 2016 owing to the excessive issuance of government bonds and corporate bonds, leading to the liquidation of time deposits. Correspondingly, inflation rose 0.6 percentage points to 2.0% in 2016, lower than the 3% target the government had set at the beginning of the year. By segment, the food, tobacco, and liquor segment and the healthcare segment are the main contributors, with an inflation rate of 3.8% for both segments in 2016. However, other segments (e.g. clothing; housing; and education, culture, and entertainment) showed lower levels of inflation at around 1.4%-1.6%. Looking forward towards 2017, China will continue its moderate monetary policy to encourage steady economic growth and to control inflation at around 3%. The PBC will continue to guarantee money-market liquidity by applying financial instruments as well as prevent asset bubbles and systemic financial risks.

Source: National Bureau of Statistic

Source: SHIBOR

Source: National Bureau of Statistics

Source: National Bureau of Statistics |

|

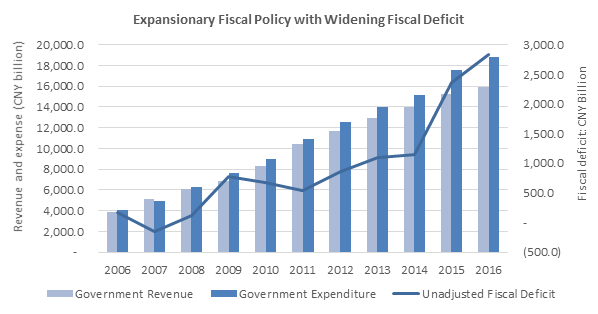

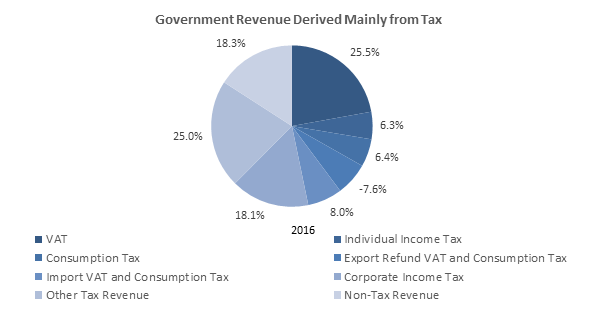

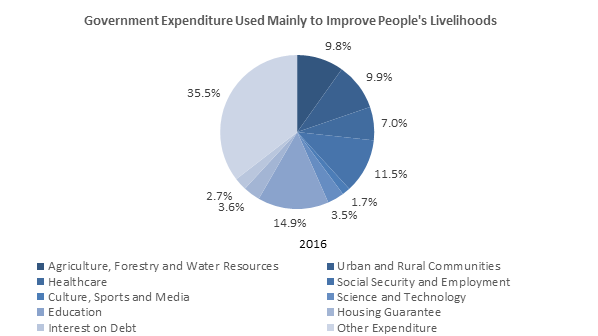

Expansionary Fiscal Policy to Support Economic Growth: Tax Reduction for Businesses and Incremental Expenditure for People’s Livelihoods China’s government revenue increased at a CAGR of 15.2% to CNY 16.0 trillion (≈USD 2.4 trillion) in 2016 from CNY 3.9 trillion (≈USD 0.5 trillion) in 2006, while government expenditure increased at a CAGR of 16.6% to CNY 18.8 trillion (≈USD 2.8 trillion) from CNY 4.0 trillion (≈USD 0.5 trillion) during the same period. The unadjusted fiscal deficit deteriorated to CNY 2.8 trillion in 2016 (≈USD 0.4 trillion) from CNY 537.3 billion (≈USD 83.1 billion) in 2011, with the deficit ratio at 3.8% in 2016. China usually adjusts its fiscal deficit by applying its central budget stabilisation fund in order that the actual result matches the estimation by the National People’s Congress (NPC). In 2016, the excess of fiscal deficit over the estimation was CNY 648.9 billion (≈USD 97.7 billion); this was finally adjusted to zero, bringing the adjusted deficit ratio to 3.0%. The government targets an adjusted deficit ratio of 3.0% for 2017, higher than the USA’s (-4.2% as of 2015) and Japan’s (-3.5%). China is pursuing an expansionary fiscal policy in 2017, aiming to increase government expenditure and to decrease tax revenue. As for government expenditure, China will focus mainly on improving residents’ livelihoods, including the promotion of employment, its healthcare subsidy, and the development of elderly care services. Expenditure on healthcare and birth control is estimated to increase 150.3% YoY to CNY 13.7 billion (≈USD 2.0 billion) in 2017 from CNY 9.1 billion (≈USD 1.4 billion) in 2016; expenditure on social security and employment is estimated to increase 111.4% YoY to CNY 99.2 billion (≈USD 14.4 billion) from 89.1 billion (≈USD 13.4 billion). In 2016, tax revenue contributed 81.7% of government revenue, down from 89.8% in 2006, despite a CAGR of 14.1% during the period. In order to eliminate repetitive taxing, relieve tax burden on businesses, and advocate the importance of the industrial chain, the government introduced a pilot program replacing business tax with a value-added tax (VAT) in 2012. As of 1 May 2016, China comprehensively adopted VAT and abandoned business tax. The accumulated tax reduction from January 2012 to February 2017 exceeded CNY 1.2 trillion (≈USD 0.2 trillion(*8)), and the proportion of the total of VAT, import VAT, export VAT refund, and business tax fell 9.2 percentage points YoY to 31.2% in 2016 from 40.4% in 2015. The government estimates that tax revenue from businesses in 2017 will decline further by CNY 500.0 billion (≈USD 72.6 billion); this will help to revitalise the economy and enhance productivity. Under the expansionary fiscal policy, aggregated demand will increase and lead to a higher price level.

Source: National Bureau of Statistics

Source: National Bureau of Statistics

Source: National Bureau of Statistics |

|

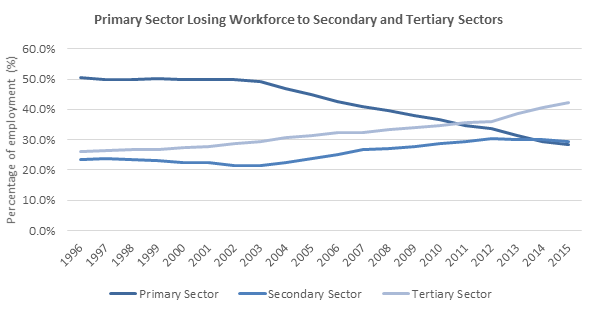

Workforce Gradually Shifting to Secondary and Tertiary Sectors from the Primary Sector alongside the Shift in the Core Economic Contributor In 2016, China’s employed population was 776.0 million (56.1% of the total population). As per the National Bureau of Statistics, the unemployment rate for urban residents stabilised at around 4.0% for the past few years. The International Labour Organisation claims a slightly higher figure for China’s unemployment rate in 2015: 4.6% versus the USA’s 4.9%, Japan’s 3.1%, and India’s 3.5%. As China largely fosters its secondary and tertiary sectors and heavily promotes urbanisation, the proportion of employment in the primary sector declined 21.7 percentage points to 28.3% in 2015 from 50.0% in 2002, while that of the secondary sector decreased 0.8 percentage points to 29.3% in 2015 from 30.1% in 2013 (after increasing 8.7 percentage points over 2002–13). Employment in the tertiary sector grew 16.4 percentage points to 42.4% in 2015 from 26.0% in 1996; this is attributable mainly to China’s changing perception of the tertiary sector. As the country aggressively promotes machinery automation in the primary and secondary sectors, employment is likely to continue shifting to the tertiary sector.

Source: National Bureau of Statistics |

|

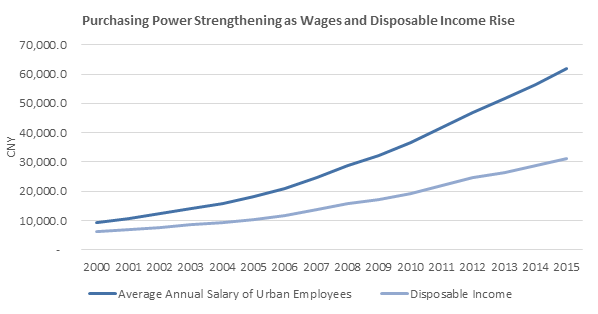

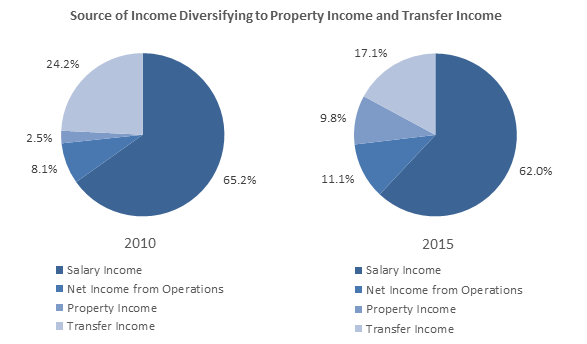

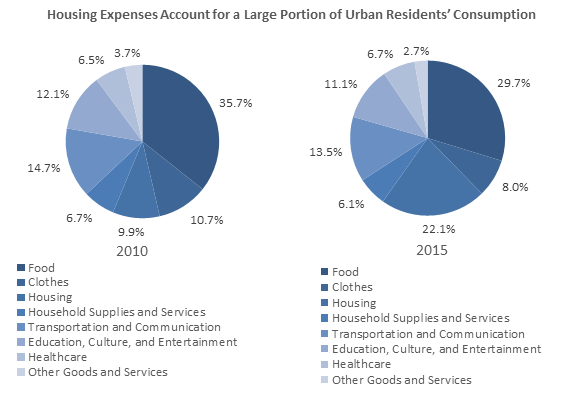

Chinese People’s Purchasing Power Strengthened, Driven by Diversifying Income Sources; Large Portion of Consumption Shifts to Housing Expenses A stable employment trend boosts growth in people’s income. Chinese people currently enjoy strong purchasing power: the average annual salary of urban employees increased at a CAGR of 13.5% to CNY 62,029.0 (≈USD 9959.9) in 2015 from CNY 9,333.0 (≈USD 1,127.4) in 2000, and per-capita disposable income of urban residents rose at a CAGR of 11.3% to CNY 31,194.8 (≈USD 5,008.5) from CNY 6,280.0 (≈USD 758.6) during the same period. In terms of income source, urban residents’ disposable income in 2015 was derived from salary income (62.0%), transfer income (17.1%), net income from operations (11.1%), and property income (9.8%). Compared with its composition in 2010, the source of income has diversified to net income from operations and property income. This indicates that people are more actively engaged in business operations and wealth management. As mentioned earlier, the real-estate sector boomed during the past few years. This phenomenon can also be observed in the structure of urban residents’ consumption. The proportion of housing expenses rose a significant 12.2 percentage points to 22.1% in 2015 from 9.9% in 2010. However, this structure might change in future when the housing market cools.

Source: National Bureau of Statistics

Source: National Bureau of Statistics

Source: National Bureau of Statistics |

|

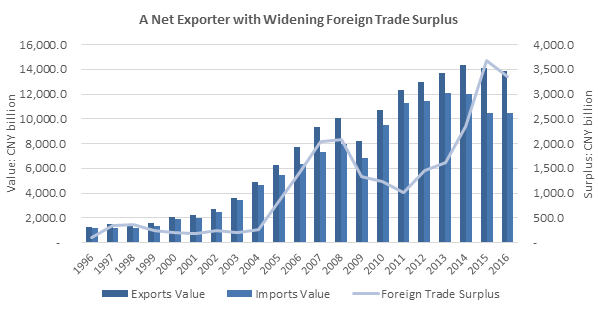

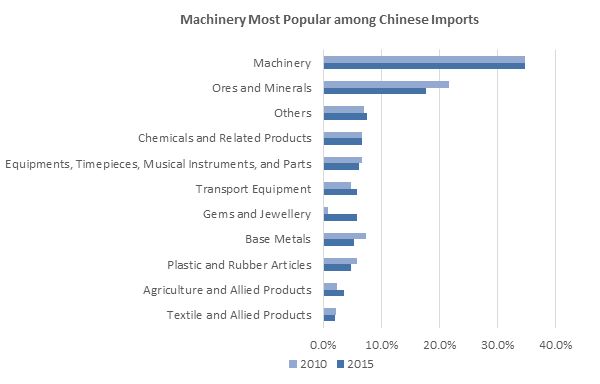

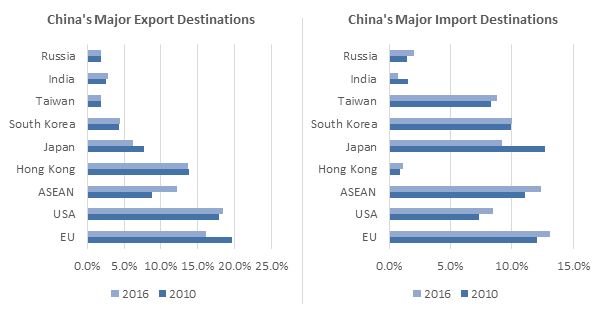

World’s Leading Net Exporter Trades Low Value-Added Products for High Value-Added Ones As of 2015, China contributed 13.8% to the world’s exports and 10.3% to the world’s imports, compared with 7.3% and 6.1% in 2005, respectively, marking impressive growth in China’s foreign trade. As a leader in international trade, China generated a total foreign-trade value of CNY 24.3 trillion (≈USD 3.7 trillion) in 2016: CNY 13.8 trillion (≈USD 2.1 trillion) in exports and CNY 10.5 trillion (≈USD 1.6 trillion) in imports. China’s foreign trade took off only after it joined the WTO in 2001, and it quickly overtook Japan in 2004, the USA in 2007, and Germany in 2009 to become the world’s largest exporter. It ranks second in terms of global imports, preceded by the USA. In terms of the types of products traded, machinery holds a dominant share in both exports and imports. Although China calls for technological advancement and R&D, most machinery exports remain low value-added, while machinery imports are usually high value-added and require advanced technology. This situation is likely to continue in the short term, as China continues to lag OECD countries in technological competency and R&D strength. China’s major export destinations include the USA (18.4% in 2016), the EU (16.2%), and Hong Kong (13.7%). The reason Hong Kong handles a large portion of mainland China’s exports is that it serves as a low-tariff transit for re-exports. Moreover, the share of exports to ASEAN countries increased to 12.2% in 2016 from 8.8% in 2010, as a result of beneficial agreements in the ASEAN-China Free Trade Area (ACFTA) effective since 2010. On the other hand, the share of exports to European countries shrank 3.1 percentage points due to soft demand in Europe, RMB appreciation in previous years, and newly levied anti-dumping duties. The main import destinations are the EU (13.1% in 2016), the ASEAN (12.4%), South Korea (10.0%), Japan (9.2%), Taiwan (8.8%), and the USA (8.5%). China has been restraining imports of certain goods from Japan following the Fukushima nuclear disaster in 2011, but Japan remains an important trading partner for China. As China gradually deepens its partnership with the countries under the Belt and Road Initiative(*9), foreign trade along the route is likely to grow.

Source: National Bureau of Statistics

Source: World Trade Organisation

Source: National Bureau of Statistics

Source: National Bureau of Statistics

Source: National Bureau of Statistics |

|

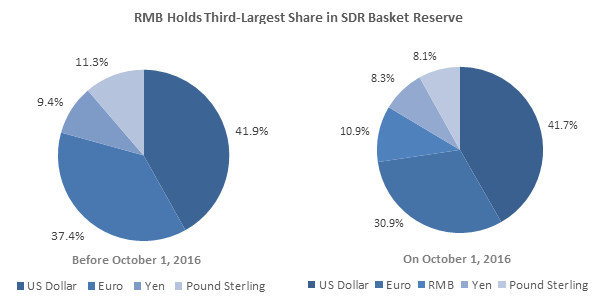

Chinese Renminbi’s Inclusion in Special Drawing Rights Basket Promotes Higher Global Currency Demand and Local Financial Market Reform Effective 1 October 2016, the Chinese renminbi (RMB) officially joined the US dollar, the euro, the Japanese yen, and the British pound in the IMF’s Special Drawing Rights (SDR) basket, becoming the fifth international reserve-asset currency. The inclusion of RMB in the SDR basket reflects the recognition of China’s reform progress and also consolidates the country’s international standing and influence. It also shows an increase in the use of RMB internationally. On the day of its inclusion in the SDR basket, RMB was granted a 10.9% weighting, following the US dollar (41.7%) and the euro (30.9%). Consequently, the embracement of RMB further encourages more than 180 members of the IMF to use RMB in international trade and bolsters global demand for RMB. On the grounds that China has established partnerships with various countries and is a major destination of foreign investment, these countries are likely to increase their RMB reserves. This will in turn allow the government to issue more RMB-denominated debt, mitigating the currency mismatch problem in the long run. In order to meet the IMF’s requirement that the currency be “freely usable”, China has gradually liberalised the RMB exchange rate and established a mechanism that sets the central parity rate to the closing rate plus the change in the exchange rate of the currency basket (to reflect changes in market supply and demand). In addition, it continuously promotes capital-account convertibility and agrees not to limit capital outflow. Other measures for further opening the financial market include allowing foreign central banks, international finance organisations, and sovereign wealth funds to trade on the interbank foreign exchange market through agents, as well as issuing the offshore RMB-denominated bond to improve offshore RMB liquidity, e.g. the central bank bill of CNY 5 billion (≈USD 0.8 billion) in London in 2015. Although the inclusion of RMB in the SDR basket will not bring immediate benefits to Chinese residents and companies, RMB will be more widely used in overseas travelling, studying, and investment in the long run due to its higher acceptance in foreign countries.

Source: IMF |

|

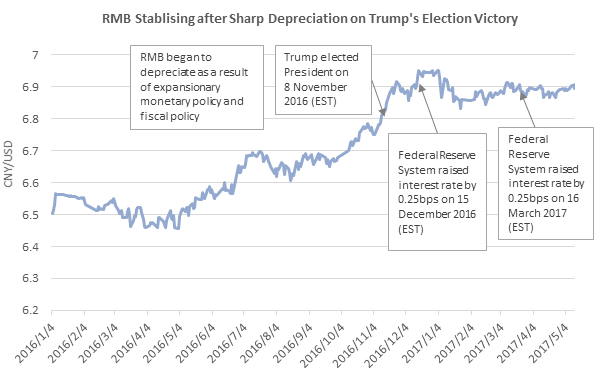

Trump’s Presidency Poses Potential Threats to Chinese Economy; Macron’s Election Victory Bodes Well for China-France Partnershi On 8 November 2016, Donald Trump defeated Hilary Clinton to win the US election. His election sped up RMB depreciation, boosting the CNY/USD exchange rate to almost 7.0 at the beginning of January 2017 from around 6.7818 on 8 November 2016. The stronger US dollar (at a CNY/USD level of 6.9) resulted from investors’ expectation of an expansionary fiscal policy and a contractionary monetary policy, as well as from the US Federal Reserve’s interest-rate increases on two occasions. Moreover, Trump plans to impose a 45% tariff on goods imported from China. As mentioned previously, the USA is China’s largest export destination (share in total exports in 2016: 18.4%), and the proposed high tariffs should reduce Chinese manufacturers’ profits or even force them to stop exporting to the USA once the higher tariffs are implemented, leading to a negative effect on the Chinese economy. This could also lead to lower demand for RMB and further depreciation of the currency. On 8 May 2017, Emmanuel Macron was elected France’s new president after he defeated his far-right opponent Marine Le Pen in the final round of the French elections. His victory ensures that France will stay in the EU and also eliminates any black swan event that might have resulted from Le Pen’s election. Macron advocates globalisation, trade openness, ease of burden on businesses, and the development of emerging industries. Macron was previously France’s economy minister, and in that role in 2015 he had defended a Chinese-led consortium’s capital injection into Toulouse Blagnac Airport, the largest airport in southwestern France. This indicates the newly elected president’s positive attitude towards foreign capital inflow into France and towards the partnership between France and China. China also attaches great significance to France and to China-France relations, and welcomes the French side’s participation in the Belt and Road Initiative. Therefore, strengthening their partnership will support trade between the two countries.

Source: State Administration of Foreign Exchange |

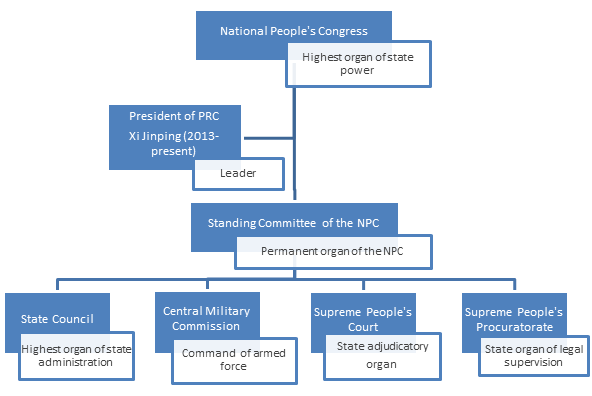

Political and Legal OverviewNational People’s Congress Is the Country’s Highest Authority and Exercises the Supreme Power of the People The National People’s Congress (NPC) was established in 1954 based on China’s longstanding belief that the people’s interests are supreme and that state power consequently belongs to the people. The NPC comprises deputies elected for a term of five years from the provinces, autonomous regions, and municipalities, and holds annual sessions every spring. Hence, the NPC is also regarded as the instrument through which people exercise state power. The functions and powers the NPC exercises include the election of the PRC’s president and vice president; the amendment, supervision, and enforcement of the constitutions; and the enactment and amendment of basic laws governing criminal offences, civil affairs, and state institutions as well as other matters. When the NPC is not in session, the Standing Committee performs the role of the highest organisation of state power. The president of the PRC is not elected directly by each individual, but rather by local-community representatives. The NPC also oversees the State Council, the Central Military Commission, the Supreme People’s Court, and the Supreme People’s Procuratorate. The State Council, along with its subordinate ministries and administrations, is responsible for implementing China’s policies and laws as well as for dealing with such affairs as diplomacy, national defence, finance, economy, culture, and education. The State Council is also empowered with drafting and implementing five-year plans and other national development strategies, e.g. the Belt and Road Strategy and Made in China 2025. Structure of the Chinese Government

Source: by UZABASE |

|

One-Party System: Communist Party Fosters Socialism with Chinese Characteristics Founded in 1921, the Communist Party of China (CPC) created the People’s Republic of China in 1949 following its victory in the ‘new-democratic revolution’. China adopts a multi-party cooperation system — CPC is the only ruling political party in the country. The other eight participating parties(*10) exist under a united front. Due to the absence of power swaps among political parties, China’s policies tend to be continuous and oriented towards the long term. For example, Deng Xiaoping raised the concept of a “moderately prosperous society” in 1979, and the CPC has set periodic goals at subsequent National Party Congresses to achieve a moderately prosperous society by 2020. Rooted in the ideology of Marxism and socialism, the CPC once pursued public ownership and democratic and social control of the means of production. Socialism advocates labour-based distribution and common prosperity; however, as a less-developed country back then, China saw a low and imbalanced level of productivity, making it impossible to strictly follow socialist ideology. After years of exploration and reform, CPC finally decided to pursue ‘Socialism with Chinese Characteristics’ at the 12th National Party Congress in 1982, and introduced a basic economic system dominated by public ownership with the coexistence of diversified economies (e.g. private capital and foreign capital). Meanwhile, it replaced its labour-based distribution model with a combination model of labour-based distribution and production factor-based distribution. Therefore, China now follows a market economy where resources and productivity are distributed based on market supply and demand. |

|

Comprehensive Legal System Administrated by the Supreme People’s Court and the Three Other Levels of Courts China’s legal system is defined as a socialist legal system that integrates Chinese characteristics. Under the Supreme People’s Court are three other levels of courts: the Higher People’s Courts, the Intermediate People’s Courts, and the Grass-roots People’s Courts. China’s legal system covers laws that fall under seven categories: Constitution and Constitution-related, civil and commercial, administrative, economic, social, and criminal, and lawsuit and non-lawsuit procedures. The laws themselves are of three levels — state laws promulgated by the NPC and its Standing Committee, administrative regulations issued by the State Council, and local statutes released by local People’s Congresses and their Standing Committee. As of end-2015, China has enforced more than 240 laws and over 700 administrative regulations governing all aspects of its political, economic, cultural, and social life. |

|

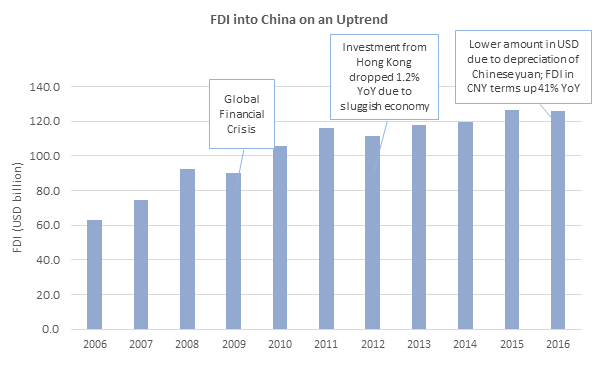

Largest Recipient of Foreign Direct Investment Globally as Government Relaxes Restrictions on Foreign Investment According to the UN, China was the world’s largest destination of foreign direct investment (FDI) inflow in 2015. Although FDI into China decreased 0.2% YoY to USD 126.0 billion in 2016 from USD 126.3 billion in 2015, this is attributable mainly to the depreciation of the Chinese yuan. FDI in Chinese yuan terms was CNY 813.2 billion in 2016, up 4.1% YoY. During 2012-15, FDI grew to USD 126.3 billion from USD 111.7 billion, registering a CAGR of 4.2%. The top-ten countries and regions constituting around 94% of total FDI in 2016 are Hong Kong (69.2%), Singapore (4.9%), South Korea (3.8%), the USA (3.0%), Taiwan (2.9%), Macau (2.8%), Japan (2.5%), Germany (2.2%), the UK (1.8%), and Luxemburg (1.1%). The State Council introduced the ‘Catalogue for the Guidance of Foreign Investment Industries’ (“the Catalogue”) in 1995 with the intention of attracting foreign capital inflow and regulating foreign investment involvement in certain industries. The Catalogue is divided into three categories: encouraged industries, prohibited industries, and restricted industries. Industries not mentioned in the list are generally permitted to receive foreign investment. Investment in these categories are subject to approval procedure and registration requirements. Those in encouraged industries face relatively loose policies, while those in restricted industries face more scrutiny. Moreover, encouraged industries are eligible for preferential policies such as tax incentives and tariff exemption quotas. China is gradually lifting restrictions on foreign business. Compared with the previous version, the amended Catalogue, issued in 2015 by the State Council and the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), halved the number of restricted industries to 38 from 79 and reduced the number of prohibited industries to 36 from 38. As a result, the service industry and the general manufacturing industry are opened up and more investor-friendly. The new draft for comment released in 2016 intends to further reduce restricted industries to 35 and prohibited industries to 27. Currently, the Catalogue primarily encourages foreign investment in modern agricultural, high-tech, advanced manufacturing, energy saving and environmental protection, and new energy industries, among others.

Source: National Bureau of Statistics

China: Restrictions for Foreign Investment Loosening

Sources: NDRC; State Council

*Note: Include both encouraged and restricted industries where foreign capital proportion is limited |

|

Establishment of Development Zones and Free Trade Zones Promote Technology Advancement and Foreign Trade Liberation In order to pursue economic reform and enhance market openness, China established the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone in 1980, based on borrowed economic-zone models from elsewhere in Asia. Over time, the development zones have grown rapidly in number and form. As of now, China has 219 economic and technological development zones, 145 high-tech development zones, 19 new areas, 11 free trade zones, and 7 special economic zones. Despite the varied direction of development and administrative powers, these development zones all offer preferential policies to both domestic-funded and foreign-funded enterprises, such as customs tariff exemptions, income tax cuts, and advantages in business approval and services. In addition, tenants of the industrial zones can take advantage of industry clusters and thereby increase their productivity. China launched the first foreign trade zone (FTZ) in Shanghai as a pilot project in 2013 to trigger institutional reform and innovation in foreign investment, international trade, and finance. In 2015, it established three more FTZs in Guangdong, Tianjin, and Fujian as well as another seven in April 2017. FTZs follow the negative-list approach for investment management instead of the Catalogue, so that all unlisted foreign investment and business activities are allowed. In addition, the authority simplifies foreign trade supervision procedures, permits post-filing supervision, and realises RMB capital account convertibility, granting the market a high level of freedom and flexibility. Development Zones in China

Source: by UZABASE

* Note: Number of zones as of 6 April 2017 |

|

Government Offers Tax Incentives for High- and New-Tech Enterprises to Enhance the Country’s Innovation and R&D Capacity Effective 1 January 2008, the NPC replaced the ‘Income Tax Law of the People’s Republic of China on Foreign-funded Enterprises and Foreign Enterprises’ and the ‘Interim Regulation of the People’s Republic of China on Enterprise Income Tax’ with the ‘Enterprise Income Tax Law of the People’s Republic of China’. The new Enterprise Income Tax Law unifies preferential policies for domestic-funded and foreign-funded enterprises, and going forward the preferential policies will apply mainly on an industry basis, with some subsidiary regional policies. In general, for small, meagre-profit enterprises, enterprise income tax shall be levied at a reduced rate of 20%, while for high- and new-tech enterprises (HNTE) it shall be levied at 15% (compared with a normal tax rate of 25%). HNTE must generate more than 60% of revenue from high-tech products (services); the percentage of R&D expenses in revenue must exceed 6% for HNTE with revenue less than CNY 50 million (≈USD 7.5 million), 4% for HNTE with revenue between CNY 50 million (≈USD 7.5 million) and 200 million (≈USD 30.1 million), and 3% for HNTE with revenue over CNY 200 million (≈USD 30.1 million)(*11). Key HNTE industries that are currently largely supported by the government: ・Electronic information ・Biology and new medicine ・Aviation and aerospace ・New materials ・High-tech services ・New energy and energy saving ・Resources and environment ・Advanced manufacturing and automation |

|

Being Highly Policy Driven Benefits Investment in Government-Supported Industries As a socialist country, China’s development depends largely on government guidance. Industry growth is therefore strongly driven by policy. Most of the key industries appointed by the government have seen significant growth in the past few years, as matched policies and incentives were also issued in order to fuel development. For example, in one of the key industries for development, new energy vehicles, production volume grew at an impressive CAGR of 178.6% to 379,000 units in 2016 from 17,533 units in 2013, under the guidance of the Planning for the Development of the Energy-Saving and New Energy Automobile Industry (2012–20). In addition to the plan, the government also offers incentives to consumers, such as free licence plates and the exemption of purchase tax in order to boost sales. Players in government-supported industries can therefore take advantage of the preferential policies and improve business performance. In May 2015, the State Council promulgated Made in China 2025, a guidance on developing domestic manufacturing technologies and improving overall productivity. The ten-year plan serves as a guideline to enhance the country’s competency in manufacturing industries. By 2020, China aims to realise industrialisation and informatisation in manufacturing and to master core manufacturing technologies for key fields. Meanwhile, energy consumption and carbon dioxide (CO2) emission is expected to improve. By 2025, the plan envisions a leap in innovation capacity and productivity as well as in green-manufacturing capability comparable to developed countries’. Therefore, led by Made in China 2025, the manufacturing industry is likely to grow rapidly in the next 10 years. Major Target Set by Made in China 2025

Sources: State Council; Made in China 2025

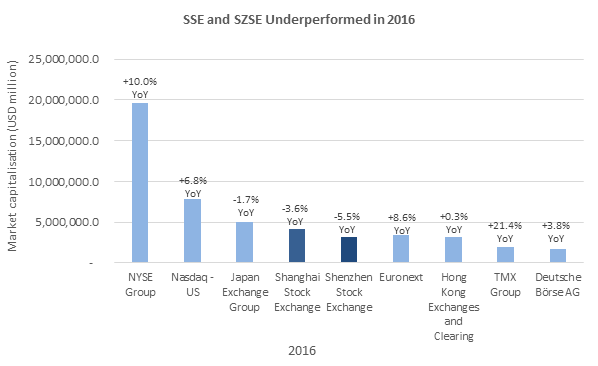

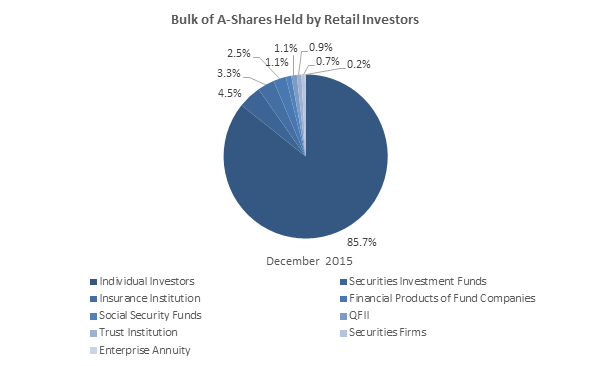

Financial OverviewWorld’s Second-Largest Stock Market with Significant Participation from Retail Investors and High Stock Turnover In 1990, the People’s Bank of China approved the establishment of the Shanghai Stock Exchange (SSE) and the Shenzhen Stock Exchange (SZSE), the two major stock exchanges in mainland China. China’s is currently the second-largest stock market in the world, with a total market capitalisation of CNY 50.8 trillion (≈USD 7.6 trillion, 68.3% of GDP) as of end-2016, second only to the US stock market (the New York Stock Exchange’s market capitalisation: USD 19.6 trillion; the Nasdaq-US’s: USD 7.8 trillion, 145.3% of GDP). The performance of China’s stock market bears little connection to the underlying economic conditions, but rather is affected by the government’s policies. In other words, the government reacts to abnormal stock-market performance by implementing corresponding policies. For example, it suspends the IPO approval process during times of high stock-market turbulence in order to help stabilise the stock market. Moreover, when the government issues policies favouring the development of specific industries, listed companies in those industries are likely to outperform others, even for just a short time. Despite continuous GDP growth, the market trended down during 2010-14. The stocks entered a bull market thereafter in 2015, wherein the SSE Index and the SZSE Composite Index peaked at 5,166.4 on 12 June 2015 and 17,889.7 on 11 June 2015, respectively. Entering H2 2015, the stock market quickly cooled, and total market capitalisation decreased 4.4% YoY to CNY 50.8 trillion (≈USD 7.6 trillion) in 2016 from CNY 53.1 trillion (≈USD 8.5 trillion) in 2015; market capitalisation as a percentage of GPD fell to 68.3% from 77.1%. The reasons for the stock market crisis were various; to name just a few: some institutional investors and listed company shareholders sold large numbers of shares at high price levels in order to realise profits, and leveraged funds that entered the bull market quit immediately at the sign of market downturn. In contrast to well-developed stock markets such as the USA’s, China’s stock market is characterised by high participation from retail investors and low engagement from institutional investors. As of 26 May 2017, the total investor accounts reached 125.0 million, of which retail investors accounted for 99.7% and institutional investors only for 0.3%. In contrast, in the US stock market, institutional investors owned around 70% of public shares. Retail investors are usually characterised as less rational, and they tend to speculate for short-term returns with a preference for ‘small cap’ stock; in comparison, institutional investors tend to make rationally planned, long-term investments, in turn contributing to the stock market’s overall healthiness. However, although the government has been actively encouraging long-term institutional investment, the participation of professional institutions such as asset management and fund management firms remains low. This phenomenon led to an extremely high turnover rate in China’s stock market in 2016 (273.2%) relative to the USA’s (154.8%) and Japan’s (116.8%). Difference between the Two Main Stock Exchanges

Sources: Shanghai Stock Exchange; Shenzhen Stock Exchange

Sources: National Bureau of Statistics; money.163.com

Source: World Federation of Exchanges

Note: YoY growth on each stock exchange is sourced from World Federation of Exchanges

Source: China Securities Regulatory Commission |

|

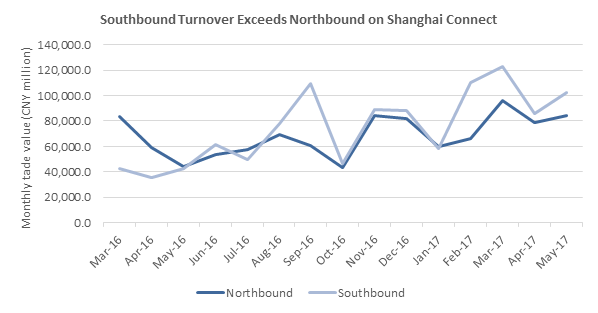

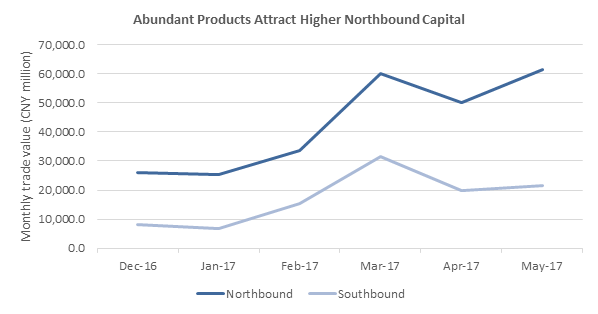

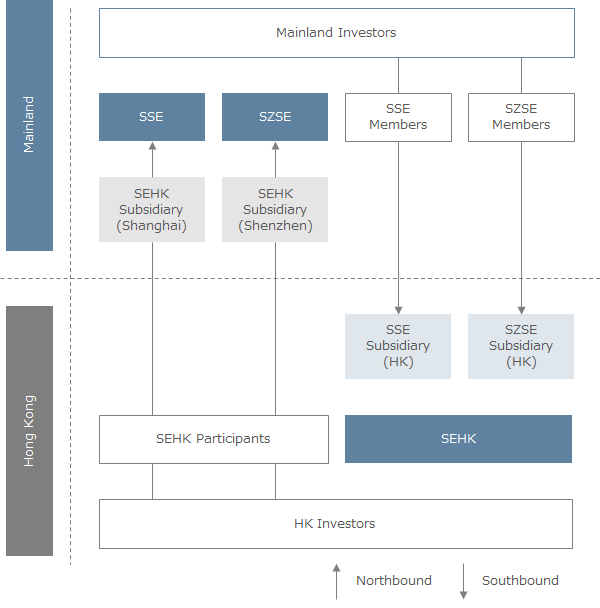

Shanghai Connect and Shenzhen Connect Intend to Attract Foreign Capital and Stimulate Institutional Investments In April 2014, the Securities and Futures Commission (SFC) and the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) approved the development of Shanghai-Hong Kong Connect (Shanghai Connect) for the establishment of mutual stock-market access between mainland China and Hong Kong. The Shenzhen-Hong Kong Connect (Shenzhen Connect) was launched later in December 2016. Under Shanghai Connect and Shenzhen Connect (together “the Connect”), investors from mainland China are able to trade shares listed on Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing (HKEX), while investors from Hong Kong can trade approved A-shares and H-shares. The Connect brings various advantages such as capital flow between the counterparts and increased involvement of foreign intuitional investments in the A-share market. In order to boost trading activities, Shanghai Connect removed the accumulated transaction limit of CNY 250.0 billion (≈USD 37.6 billion) for southbound stocks and that of CNY 300.0 billion (≈USD 45.2 billion) for northbound stocks. The Connect now implements a daily limit of CNY 10.5 billion (≈USD 1.6 billion) for southbound stocks and of CNY 13.0 billion (≈USD 2.0 billion) for northbound stocks. Nevertheless, the limit was taken up only on the first few days after the launch, and as of now only around 10%-30% of the daily limit is used for Shanghai Connect and around 10%-15% for Shenzhen Connect, rendering the relaxation of the daily limit ineffective. Meanwhile, Shanghai Connect is seeing a surplus of southbound capital over northbound capital, potentially due to foreign investors’ unwillingness to invest in the A-share market, which has been underperforming since H2 2015. On the other hand, Shenzhen Connect appears to be more attractive to Hong Kong investors due to the availability of small-cap stocks on its Small and Medium-sized Enterprises Board and Growth Enterprise Board, in addition to those on the Main Board.

Source: Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing

Note: Southbound value converted to CNY from HKD based on exchange rates in Appendix 2

Source: Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing

Note: Southbound value converted to CNY from HKD based on exchange rates in Appendix 2

Process Flow at Shanghai Connect and Shenzhen Connect

Source: Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Note: The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong is a subsidiary of Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing |

|

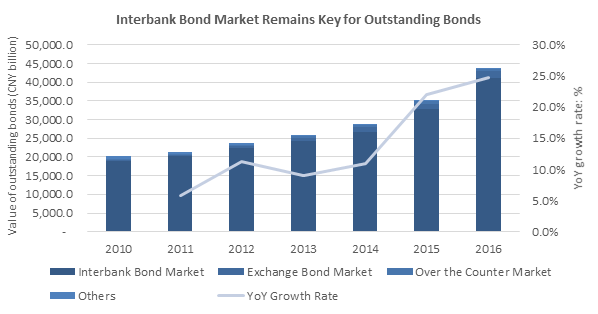

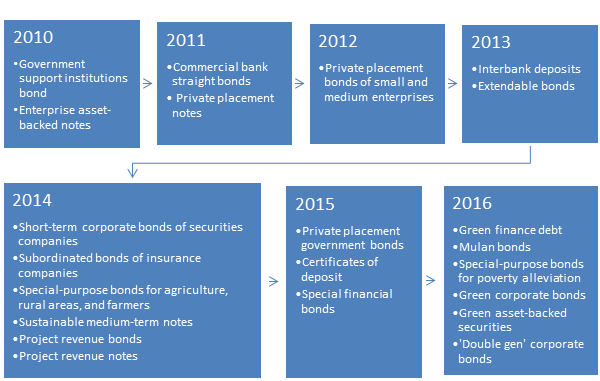

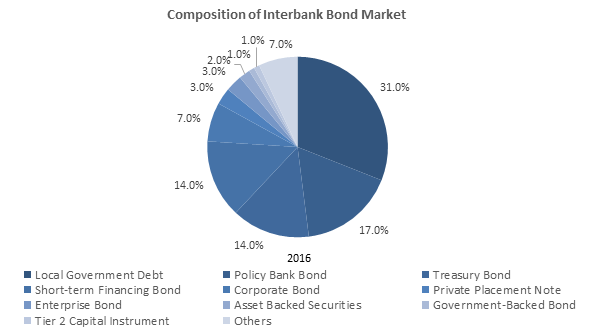

Proliferation of Bond Products Catering to High Engagement of Institutional Investors; Downgrade by Moody’s on China’s Credit Rating Remains Questionable Established in 1981, the bond market in China plays an important role in the financing of infrastructure construction. For instance, the Shanghai government issued a government bond with a value of CNY 40.9 billion (≈USD 5.9 billion) in May 2017. This will finance the reconstruction of urban areas, the obtaining of land reserves, and the building of indemnificatory housing. Previously, the construction of Expo Park in Shanghai was financed by a corporate bond with a value of CNY 1.5 billion (≈USD 0.18 billion) in 2005. The three major trading venues in China are the Interbank Bond Market (IBM), the Exchange Bond Market, and the Over the Counter Market. The IBM holds about 94% of the total amount of outstanding bonds. As of end-2016, the total value of all outstanding bonds reached CNY 43.7 trillion (≈USD 6.6 trillion, 58.7% of GDP), registering a CAGR of 13.8% during 2010-16. In contrast to the stock market, the main participants in the IBM are institutional investors. China has been diversifying its bond portfolio in recent years. In December 2015, China introduced the climate bond, comprising onshore bonds (72.0%), offshore bonds (27.0%), and panda bonds(*15) (1.0%). As of 2016, China issued climate bonds with a total value of CNY 238.0 billion (≈USD 35.8 billion), becoming the largest issuer of climate bonds in the world in one year (around 39% of the global issuance). Financing from climate bonds is applied mainly to the fields of clean energy (21.0%), energy saving (18.0%), clean transportation (18.0%), pollution prevention (17.0%), resource saving and recycling (17.0%), and ecological protection and climate-change adaptation (8.0%). On 24 May 2017, Moody’s downgraded China’s credit rating to A1 from Aa3 for the first time since 1989, as it believes the Chinese economy’s decelerating growth and mounting debt will lead to economic erosion over the coming years. However, the Chinese government strongly disagrees with the downgrade and claims that the risk is under control. Local governments are not allowed to obtain financing from any sources other than through the issuance of government debt; local government bonds (CNY 15.3 trillion, ≈USD 2.3 trillion) and central government bonds (CNY 12.0 trillion, ≈USD 1.8 trillion) together accounted for 36.7% of GDP in 2016, much lower than the debt-to-GDP ratios of Japan (around 234%, 2015), the USA (around 126%, 2015), Brazil (67.5%, 2015), and India (50.3%, 2013). Moreover, China has implemented tighter restrictions on local government financing in order to control its growing debt. Although it is true that its economic growth has slowed in recent years, the country’s GDP is maintaining an uptrend, and estimated YoY growth should stay at around 5.9% in 2020, as per the IMF. In this light, China’s downgrade by Moody’s seems questionable.

Source: Chinabond.com.cn

Introduction of New Bonds

Source: China Central Depository & Clearing

Source: China Central Depository & Clearing |

|

Alternative Listing Process Offers Multiple Paths to Financing China aggressively supports the development of micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs), and in 2013 it launched the National Equities Exchange and Quotations (NEEQ). NEEQ serves innovative, entrepreneurial, and growth-oriented MSMEs on equity transfers, bond financing, and asset reorganisation, among other areas. As of 2016, 10,163 companies were listed on NEEQ, with a total market capitalisation of around CNY 4.1 trillion (≈USD 0.6 trillion). The operation of NEEQ introduces a new way for MSMEs to receive financing for their development and to expand the horizon for retail investor investments. As of end-2015, MSMEs in advanced manufacturing, information transmission, and software technology accounted for 73.3% of the total number of companies listed on NEEQ. Back-door listing is an alternative way for a private company to list on the stock exchange and thereby avoid the time-consuming and costly process of an initial public offering (IPO). The method is particularly popular in China, as the State Council and the CSRC postpone IPOs in times of strong stock-market volatility. In back-door listing, a private company will go through an equity transfer, an asset swap, or a share acquisition in the secondary market and pay a premium to the public shell company, resulting in a win-win situation. In the past few years, a number of companies listed on foreign stock exchanges sought to delist from them in order to go public on the SSE or the SZSE, as these two latter usually provide a higher company valuation and therefore more financing. The high demand for public shell companies boosts premiums drastically. Therefore, the authorities have tightened regulations on back-door listing, so that the approval process will become similar to that of IPOs. Further, a company formerly listed on a foreign bourse cannot be valued at more than 20 times the forecast profit. In this manner, the market can be regulated effectively and unreasonable speculation can be curtailed. |

|

Appendix 1 – Key Statistical Indicators

* Note: Converted at average CNY/USD conversion rate as sourced by Oanda

** Note: Based on converted GDP in USDSources: National Bureau of Statistics, www.gov.cn, Ministry of Finance, World Bank, Oanda |

|

Appendix 2 – Currency Conversion

Sources: Oanda.com for 2000–17; National Bureau of Statistics for 1986

Source: Oanda.com |

|

Notes *1.This report will focus primarily on Mainland China. *2.Currency conversions provided for reference in this report is based on the exchange rates of corresponding periods provided in Appendix 2. *3.The Eight-Nation Alliance comprises the Empire of Japan, the Russian Empire, the British Empire, the French Third Republic, the United States, the German Empire, the Kingdom of Italy, and the Austro-Hungarian Empire. *4.China is classified as a lower-middle-income country by the World Bank. *5.Urban population includes all residents in urban areas who hold either urban Hukou (household registration) or rural Hukou *6.985 and 211 Projects were the national projects to promote the development of the Chinese higher education system. *7.Supply-side form focuses on the elimination of excessive productivity in the manufacturing industry, the destocking of commercial housing, the deleverage of local government debt, reduction in costs of manufacturing industry, and addressing weakness in public infrastructure, people’s livelihoods, environmental protection, human capital, etc. *8.Converted at the average ask rate for CNY/USD at 6.889065 as sourced by Oanda.com from Jan 1 2017 to May 31 2017. *9.Belt and Road Initiative (also known as One Belt, One Road Initiative) was officially introduced in 2015 as an economic development framework. The initiative unveils China’s plan to partner with over 100 countries and international organisations along the ancient Silk Road and maritime routes on infrastructure construction, transport, and economics. *10.The eight participating parties are the Revolutionary Committee of the Kuomintang, Chinese Democratic League, China Democratic National Construction Association, China Association for Promoting Democracy, Chinese Peasants’ and Workers’ Democratic Party, Zhigong Party, Jiu San Society, and Taiwan Democratic Self-Government League *11.Converted at 2016 CNY/USD exchange rate as provided in Appendix 2 *12.A-share stocks are RMB-denominated stocks traded in RMB *13.B-share stocks are RMB-denominated stocks traded in foreign currencies *14.Stocks under special treatment are stocks that are facing financial issues or other abnormal conditions, making it hard for investors to predict their future movements. Interest of investors might be endangered by these stocks *15.Panda bonds is a RMB-denominated bond from a non-Chinese issuer, sold in mainland China |