Will US Shale Oil Drown OPEC Dominance?

|

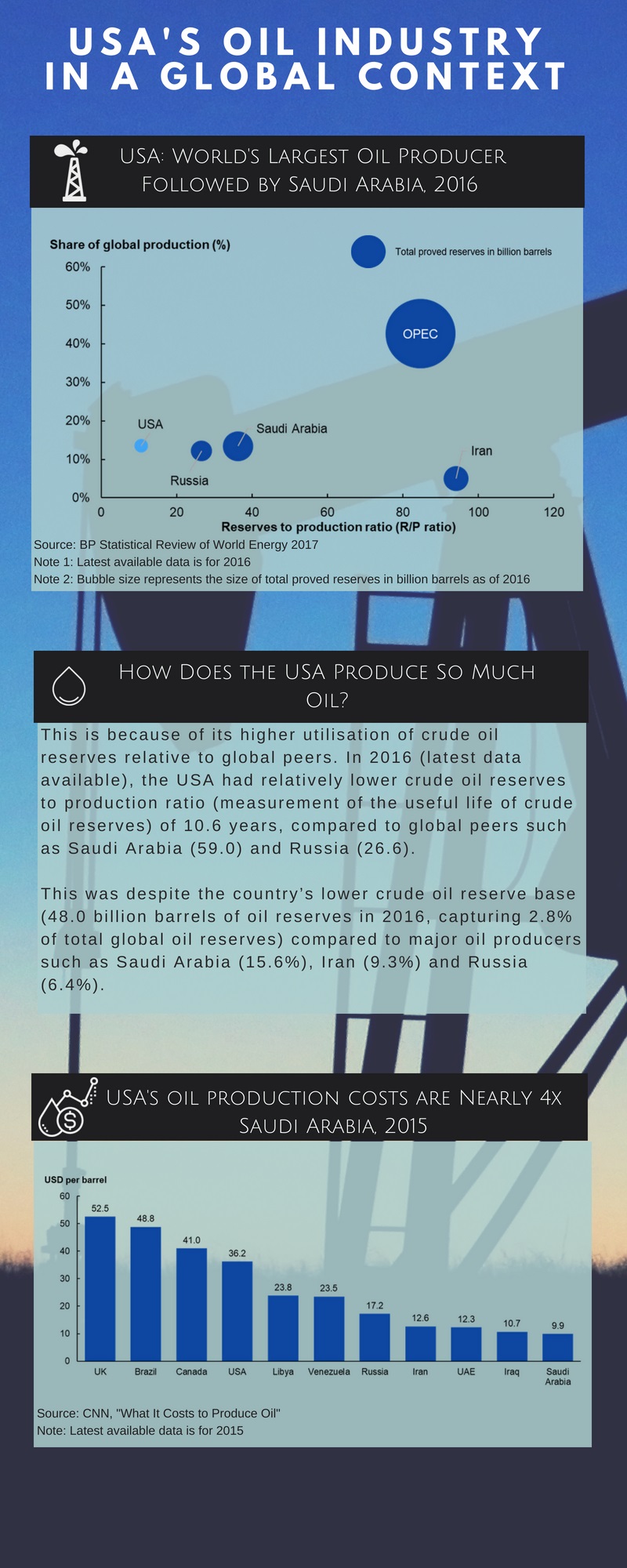

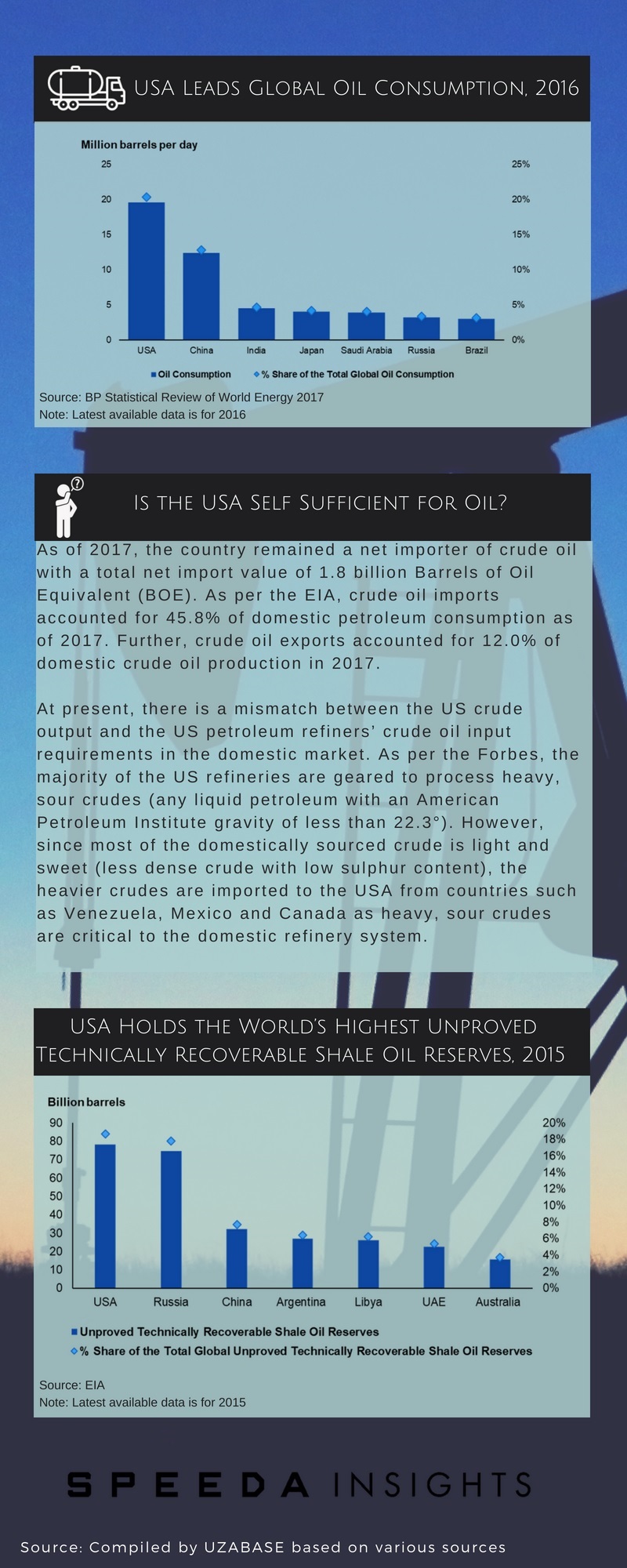

The US oil and gas industry has in recent years undergone significant transformation, during what is often referred to as the ‘shale revolution’. In 2016, as per the BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2017, the USA was listed as the largest oil producer in the world, contributing 13.5% of the world’s crude oil production. This was on the back of the country’s high extraction rates for shale oil, supported by continued technological development in hydraulic fracturing. |

|

The US Energy Information Administration expects the USA to become a net exporter of energy by 2022 which is expected to be supported by the country’s transition in becoming a net exporter of crude oil by 2027 for the first time since the 1950s, ten years after the year it is projected to become a net exporter of gas. This expectation was increasingly fuelled by the Obama administration’s decision to lift the country’s 40-year ban on crude oil exports in 2015, and is also supported by the shale revolution and the Trump administration’s move to make the USA energy independent. This has led many industry experts to believe that the shale revolution will have a significant global impact. According to the OPEC, however, the USA will not play a critical role in the global crude oil export market in the long term. |

|

We conclude that the shale revolution will make the USA increasingly self-sufficient after 2030, and that the OPEC is most likely to continue to cater to the bulk of global oil demand. In addition, the USA and the OPEC are likely to contribute the most to global growth in oil exports in the medium term (2016–30), thereby allowing the USA to exert some influence on global prices. Despite this, the OPEC’s dominance in the global oil export market in both the medium and the long term (2016–40) should remain unchallenged. We recognise that the growth seen in shale oil production has partly been supported by the Trump administration, with a series of radical shifts currently occurring in the market. However, any future change of administration that shifts the country’s energy policy away from the use of non-renewable fuels could lower domestic demand for oil; such an event could in turn further increase the USA’s share of global oil exports. |

|

Note |

|

1. Shale oil is part of a broader category of unconventional oil (tight oil) trapped in low-permeability formations. However, media sources use the term shale oil and tight oil interchangeably when discussing oil extracted from low-permeability formations. Hence, we will also follow this convention and refer to the entire tight oil category as shale oil. Furthermore, any references to crude oil also include shale oil. |

|

2. US production data from the EIA and from BP slightly differ due to variations in definitions. BP data was used for positioning the USA relative to global peers, and EIA data was used for gauging domestic performance. |

|

US Shale Revolution to Alter Country’s Oil Trade Balance |

|

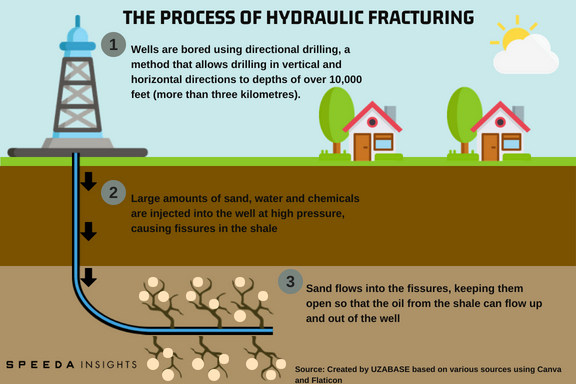

Global energy markets have been transitioning rapidly since the mid-1990s, with developments in both the demand and the supply side. However, the recent boom in US crude oil production, often referred to as the ‘shale boom’, has become one of the most significant events in the recent history of the oil markets. Shale oil refers to conventional oil (light oil with a low sulphur content) that is trapped in tight formations with low permeability, known as ‘shales’. Sites of shale exploration and extraction are known as ‘shale plays’. The extraction of shale oil is difficult compared with that of standard crude oil. Shale oil extraction has largely been possible due to the combination of horizontal drilling techniques, together with hydraulic fracturing (also called ‘fracking’). Rising oil prices have also made shale exploration more feasible. The following infographic illustrates the fracking process used today in the USA. |

|

|

|

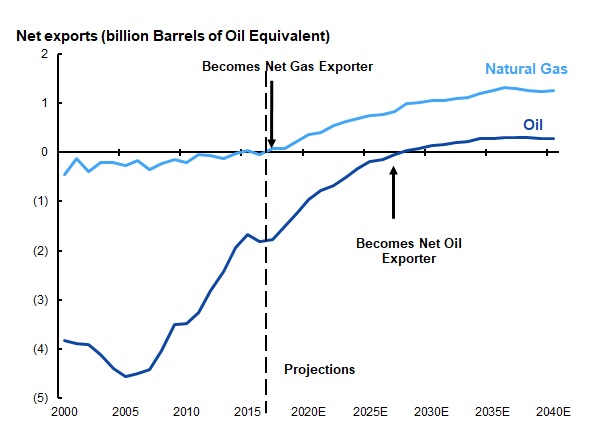

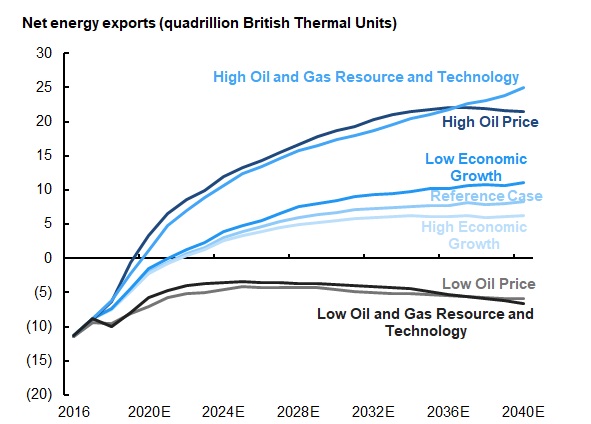

As a result of the shale revolution, as per the Guardian, the International Energy Agency (IEA) forecasts that the USA will be a net exporter of crude oil by 2027 for the first time since the 1950s. This is expected to occur ten years after the year the USA is projected to become a net exporter of gas, according to the same source. The trend was also supported by the Obama administration’s lifting of the USA’s 40-year ban on crude oil exports in 2015. As per the US Energy Information Administration (EIA), the USA is projected to become a net exporter of energy by 2022, supported by the continued discovery of both shale oil and gas resources. As per the IEA, the transition of the country’s status to a net exporter of oil from being a net importer is likely to have consequences for both the USA and the rest of the world. For the USA, this transition is in line with President Trump’s goal for the USA to achieve energy independence, and the further aim to expand its global market for energy and subsequently to make it energy dominant. This could spur other oil producing countries to challenge the US oil revolution, as OPEC members have done before. |

|

USA Forecast to Become a Net Exporter of Oil by 2027E |

|

|

|

Source: Estimated by UZABASE based on the Guardian, “US will become a net exporter within 10 years, says IEA” |

|

USA on Track to Become a Net Exporter of Energy by 2022E Under Most Projection Scenarios |

|

|

|

Source: EIA, “Annual Energy Outlook 2018” |

|

|

|

|

|

OPEC to Continue to Dominate Global Oil Export Landscape, Despite USA’s Projected Higher Contribution to Its Growth |

|

The global impact of the USA’s shale revolution is likely to be influenced by current and future prices of oil. In fact, one of the world’s longest geopolitical struggles has been over the price of oil. In contrast to many other economic wars, such as the global currency war, where countries devalue their respective currencies to boost exports, the oil price war is often between governments and private corporations. In general, this conflict is often seen between the OPEC and private American oil companies, which are applying new technology for fracking shale. For most of history, OPEC and non-OPEC countries such as Russia have influenced price movements, as there was no strong competition outside of governments. However, following the introduction of fracking, the USA entered the global arena and has begun to challenge other governments’ influence on the oil price, as discussed below. |

|

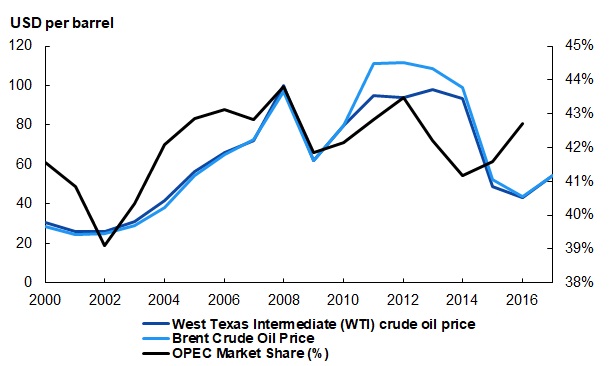

OPEC Market Share Improves Post 2014, Following Decline in Prices |

|

|

|

Source: EIA, “Spot Prices – Annual”; BP, “BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2017” |

|

Note: Latest available data for OPEC market share is from 2016 |

|

Global oil price movements and their effect on US oil production can be studied under three phases: 1) 2008–14, 2) during 2014, and 3) from 2014 to date. |

|

During the first phase (2008–14), oil prices rose to an all-time high of USD 96.9 per barrel in 2008, according to the Brent Crude Oil price. This was a result of stronger historical economic growth prior to 2008, leading to increased demand for crude oil. A supply decrease from Nigeria and Iraq contributed to the price rise. This, in turn, supported the shale revolution. During this phase, two main factors contributed to the growth of US oil production: the availability of funding and new technology. Banks were willing to issue debt to oil companies to finance shale wells, as reserves looked promising. Furthermore, new technology made fracked wells more economically reliable and also allowed oil companies to tap into previously unviable oil in shale rock. This helped increase US oil production at a CAGR of 9.8% over 2008–14 to 8.8 million barrels per day (MMbbl/d) in 2014 , as per the EIA. However, until the end of 2014, due to geopolitical turmoil in Libya and Iran, surplus oil from the USA did not alter global oil prices. |

|

In 2014, market dynamics began to shift. Many of the global disruptions eased and demand started to weaken, especially in China, Japan, and Germany, due to economic weakness. The combination of weaker demand and increasing supply from the USA caused a downtrend in oil prices. The OPEC then started losing market share (as illustrated above), in turn causing the market to crash. However, after the initial price crash, the OPEC did not immediately cut production. Feeling challenged by the USA’s increasing production and desperate to maintain its market share, Saudi Arabia chose a different strategy. Instead of cutting production to keep prices high, the OPEC decided to let prices continue to fall – an action it could sustain due to its low cost of production. As a result, fracking operations, which had expanded in the USA when oil prices were above USD 100 per barrel, now faced high breakeven costs to stay in business. For instance, breakeven costs in 2014 were nearly double the levels in 2017 (as discussed below). Consequently, the OPEC regained some of its market share. However, despite that short-term benefit, the glut that shale producers had created continued, and oil prices declined until 2016. |

|

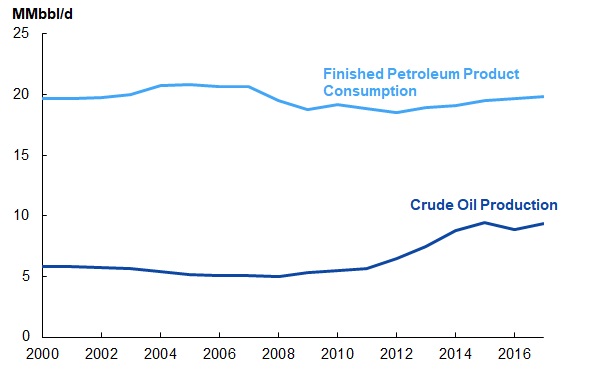

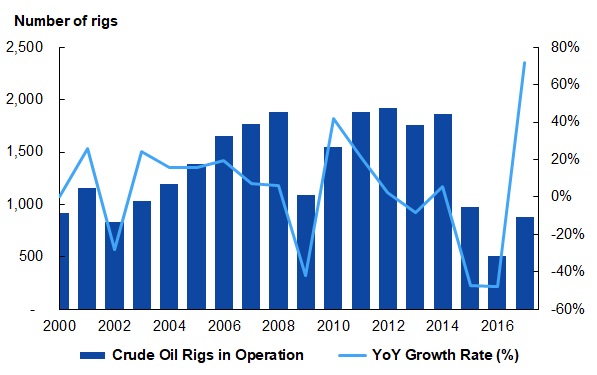

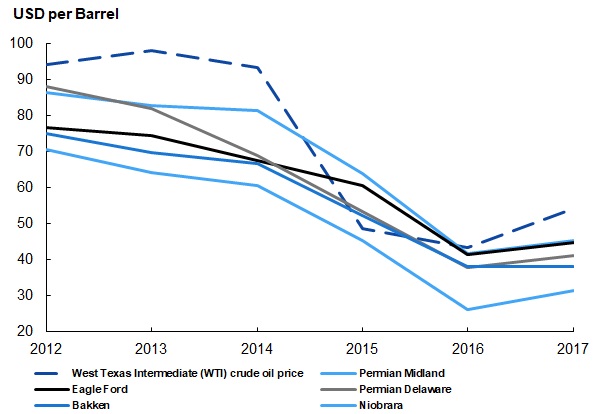

Initially, many fracking firms went bankrupt, as prices stayed low and breakeven costs were high. However, some surviving US shale producers started to find alternate ways to improve their fracking process. Subsequently, their efficiency increased (for instance, the average speed of well completion increased to 21 days from 35 days). Furthermore, breakeven costs declined over 2012–16 (illustrated below). However, in 2017, wellhead breakeven costs by shale play increased due to increasing unit and production costs. Although cyclical costs pushed breakeven prices up slightly, Rystad Energy (an energy research and business intelligence company) believes that the WTI price of USD 54.1 per barrel in 2017 was sufficient for the US shale industry to grow and that the increase only marginally impacted production activities. Consequently, as per the EIA, US crude oil production bounced back by 5.6% YoY to 9.4 MMbbl/d in 2017, subsequent to a decline of 5.9% YoY to 8.9 MMbbl/d in 2016. The recovery was strongly aided by a rise in oil field drilling activities, where crude oil rigs in operation increased 72.3% YoY to 703 rigs in 2017, subsequent to a decline of 69.9% over 2011–16 to 408 rigs in 2016. Furthermore, the USA’s steadily growing petroleum product consumption has also been fuelling oil production activities in the country, as illustrated below. |

|

Increasing Drilling Activities, Coupled with Rising Petroleum Consumption, Support Growth in Crude Oil Production |

|

USA Production and Consumption |

|

|

|

Crude Oil Drilling Activity |

|

|

|

Source: EIA |

|

Wellhead Breakeven Costs by Shale Play Rebound in 2016 After Decline |

|

|

|

Source: World Oil, “Rystad Examines What to Expect from U.S. Shale Break-Even Prices in 2017” |

|

Note 1: Latest available data is for 2016 |

|

Note 2: Contribution to total crude oil production by shale play as of April 2018: Permian (45.7%), Eagle Ford (19.3%), Bakken (17.2%), Niobrara (8.3%) |

|

The OPEC subsequently decided that it was more important to eliminate the global oversupply of oil than to maintain market share, and therefore implemented a coordinated round of production cuts starting November 2016, making its first production cut after eight years. These cuts continued to last until March 2018, gradually allowing the oil price to rise again. Pressures on US fracking eased, and the US shale oil industry suffered less than previously expected from the OPEC’s initial strategy to let prices fall. |

|

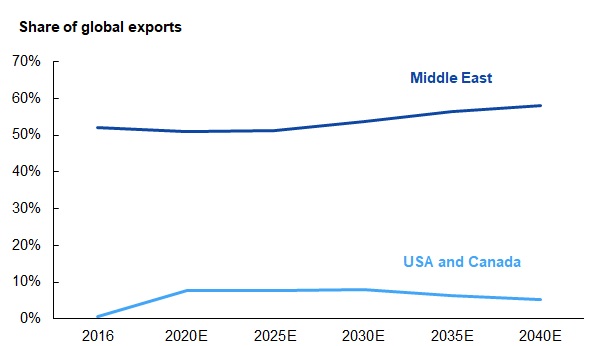

Middle East Projected to Dominate Global Oil Export Market over 2016–40; US Oil Export Share to Contract Post Production Peak in 2030 |

|

|

|

Source: OPEC, “2017 World Oil Outlook 2040” |

|

Note 1: Latest available data for actuals is from 2016 |

|

Note 2: The Middle East is used as a proxy for OPEC |

|

Consequently, as per the OPEC, the global supply of oil is expected to increase at a CAGR of 0.8% over 2016–30E to 107.6 MMbbl/d in 2030E. The growth over the period is expected to be led by US production (the USA’s projected contribution to growth: 49.2%), which is expected to grow at a CAGR of 2.0% over 2016–30E (latest available data for actuals) to 23.9 MMbbl/d in 2030E. The OPEC is expected to follow in second place (projected contribution to growth: 44.9%), with production expected to grow at a slower CAGR of 0.9% over the same period to 44.1 MMbbl/d in 2030E. Although US output is expected to boom as a result of new low-cost drilling technology, the OPEC expects US shale oil production to peak by 2030, as shale wells exhaust their output more rapidly than do other sources. Post-2030, the global supply of oil is projected to grow at a slower CAGR of 0.3% over 2030E–40E to 111.3 MMbbl/d in 2040E, with growth expected to be driven by the OPEC. |

|

As per the same source, global crude oil exports are expected to increase at a CAGR of 0.9% over 2016–30E to 42.0 MMbbl/d in 2030E (39.1% of global demand in 2030E). This growth is forecast to be led by the USA (projected contribution to growth: 66.7%), with exports set to grow at a CAGR of 22.4% over the same period to 3.4 MMbbl/d in 2030E, followed by the Middle East (projected contribution to growth: 66.7%; CAGR of 1.1% over same period to 22.6 MMbbl/d in 2030E), with other regions such as Africa, Europe, and the Asia-Pacific region set to offset some of the growth. Growth in the US export market is likely to occur with strong support both from the Trump administration and the effect of Obama administration’s lifting of the export ban, which is likely to impact oil prices in the short term. After the projected US oil peak, global exports are expected to rise at a CAGR of 0.4% over 2030E–40E to 43.9 MMbbl/d in 2040E (39.5% of global demand in 2040E), with growth driven by the OPEC. Hence, while US exports are expected to contribute significantly to export growth in the short term, OPEC exports are likely to contribute the most to global demand in the long term. In turn, it is likely that the shale revolution will make the USA increasingly self-sufficient after 2030, with the OPEC continuing to cater to the bulk of global oil demand. |

|

However, our conclusion has the following limitations: |

|

1. The increase in oil production in the USA is partly supported by the Trump administration, where a series of radical shifts have either occurred and are likely to occur in the oil and gas industry. However, any change of administration in future that pushes policy to reduce the use of non-renewable fuels could lower domestic demand for oil and in turn increase US oil exports. |

|

2. The impact of future oil prices has not been considered, given the volatility of oil as a commodity. |