Will Foreign Funds Takeaway from Private Investment, as the Philippines Enters the Golden Age of Infrastructure?

|

‘Dutertenomics’ is the term coined for President Duterte’s ambitious socio-economic development plan. A significant part of this development plan is based on the mantra of ‘build, build, build’ and aims to usher a ‘golden era of infrastructure’ in the Philippines over 2017-22F. |

|

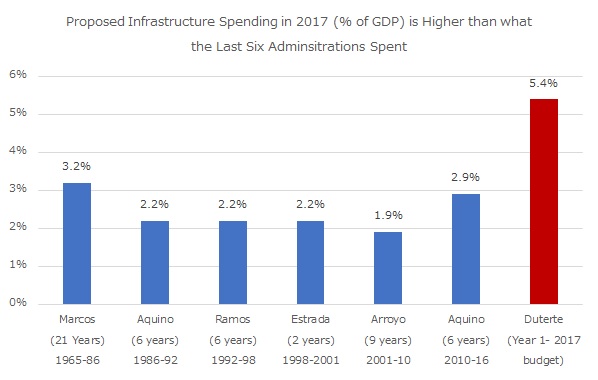

As per government sources, this plan requires PHP 8.4 trillion to be spent on infrastructure development in the Philippines over a five-year period, and is expected to push infrastructure spend up to 7.4% of GDP by 2022F from 5.4% in 2017, and is higher than the annual average infrastructure spending of the previous six administrations. As per the current plan of the government, 66% of infrastructure spending under Dutertenomics is to be funded by tax revenue. The remainder is to be financed via Private Public Partnerships (PPP) and Overseas Development Assistance (ODA), accounting for 18% and 15% of overall planned spending respectively. This heavy dependence on taxes is based on the government’s reluctance to increase the country’s external debt, thus limiting its reliance on ODAs. Moreover, its aversion to PPPs stems from the delays in awarding PPP contracts in the past. However, the government’s ability to fund infrastructure projects without pushing up its budget deficit beyond its desirable level is questionable. This may, therefore end up with PPPs and ODAs getting a bigger share than what was originally accounted for, with PPP contribution having the potential to increase from 26%-37% and ODA potential growing from 23%-34%. While both these alternatives have their pros and cons, the government is showing an inclination towards ODAs, on the back of previous failures in the PPP process, and the growing interest shown by Asia in investing in the Philippines’ infrastructure. However, this will require the Philippines to sacrifice its desired debt to GDP ratio to a certain extent. |

|

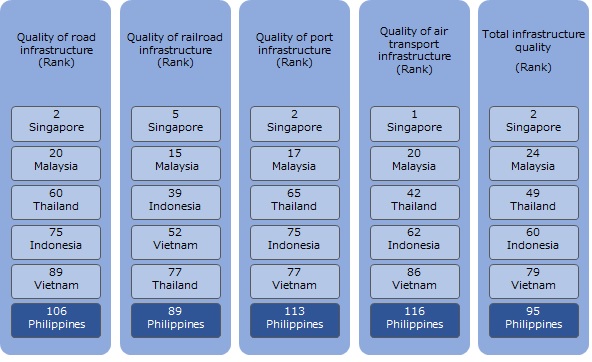

Insufficient Spending in the Past has Resulted in Sub-Standard Infrastructure, Making Dutertenomics a Necessity The Philippines is currently ranked the lowest in terms of quality of infrastructure among the ASEAN 6. As per the World Economic Forum Global Infrastructure Competitiveness Index 2016-17, out of 138 countries, the Philippines was ranked 95th in terms of the overall quality of infrastructure. The Philippines especially lagged in air transport infrastructure (116th), port infrastructure (113th) and road infrastructure (106th). The Philippines Ranked the Lowest Among ASEAN 6 in terms of Infrastructure Quality in 2016-17

Source- World Economic Forum, “Global Infrastructure Competitiveness Index 2016-17

The sub-standard levels of infrastructure have largely been a result of low infrastructure spending in the past. As per the Philippines Infrastructure Transparency Portal (PITP), Duterte’s planned spending on infrastructure (as a percentage of GDP) in 2017 is almost twice the annual average infrastructure spend of the more recent five administrations.

Source- PITP based on data from the Philippine Institute for Development Studies 2017 National Expenditure Programme

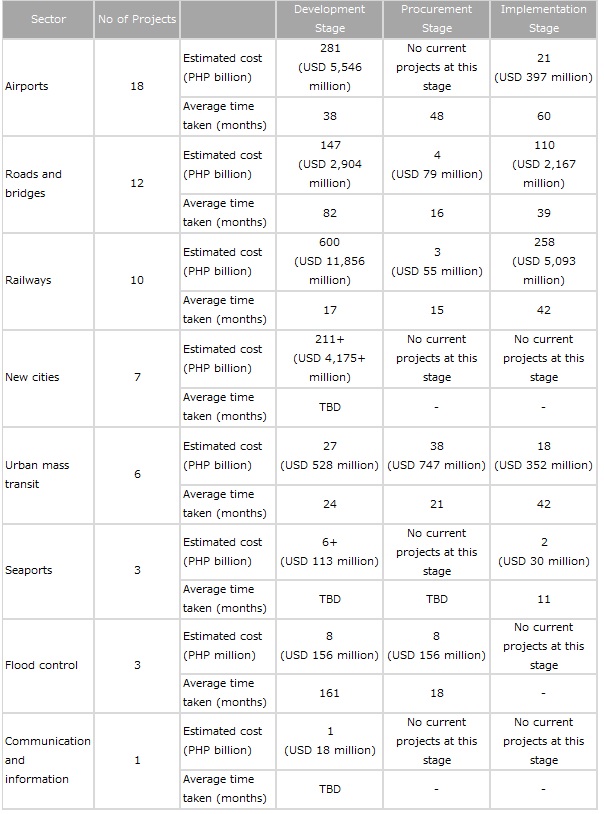

As per KPMG, these insufficiencies in infrastructure have resulted in a loss to the country in terms of productivity and efficiency and has increased travel time of Filipinos, traffic congestion, pollution, and has reduced access to basic utilities. Moreover, a study conducted by the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) in 2012 revealed that the under developed infrastructure caused the country to lose PHP 2.4 billion daily or approximately PHP 876 billion per annum, equivalent to 8.3% of GDP. With the intention of uplifting the level of infrastructure in the country, major infrastructure agencies within the national government, the National Economic Development Authority (NEDA); the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH); the Department of Transportation (DOTr); and the Bases Conversion and Development Authority (BCDA), have started to coordinate and come under the same ‘Build Build Build’ programme as implementing agencies. As per this programme, the following sectors have been selected as areas of focus: •Airports •Roads and bridges •Railways •New cities •Urban mass transport •Seaports •Flood control •Communication and Information The Philippines currently has 60 infrastructure projects in the pipeline, 39 of which are in the development stage, 5 in the procurement stage and 16 in the implementation stage. Out of these 60, 23 projects were initiated during the past year under the Duterte administration. The projects range from an estimated cost of USD 3.3 million (Night Rating of Naga Airport) to USD 4.5 billion (Mega Manila Subway). It can be observed that the number and the value of the projects in the development stage are a lot higher than those in the implementation stage, indicating the Duterte administration’s keenness and commitment towards infrastructure development. As of July 2017, the 39 projects in the development stage totalled an estimated cost of USD 21.4 billion. It could be further observed that in the majority of sectors, projects took a longer time to pass through the pre-implementation stages, as opposed to the actual implementation of the project. The longest average time taken in pre-implementation was witnessed in flood control and roads and bridges projects, whereas airport projects saw the longest average implementation time. Infrastructure Projects- Costs and Time

Source-PITP

*Note-Converted using exchange rate as of 25/7/2017

TBD-To be disclosed |

|

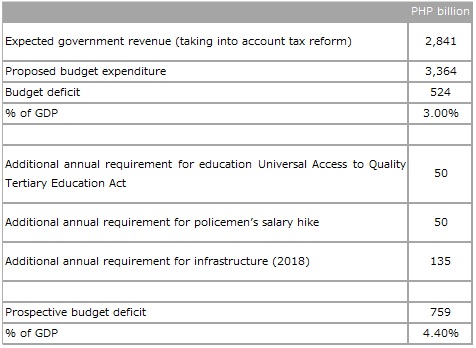

Tax Reforms Impede Government Funding Capabilities; Creates Opportunities for Alternative Sources In order to meet the requirements for the government funded portion of this plan, PHP 5.5 trillion needs to be collected as tax revenue over the course of five years, solely for financing infrastructure projects (an average of PHP 1.1 trillion per annum). To put things in perspective, the average tax revenue collected for the past five years (2012-16) amounted to only PHP 1.3 trillion per annum, with PHP 1.6 trillion being raised in 2016. As per the 2017 proposed budget, the government expects to collect PHP 2.4 trillion through taxes. However, only PHP 780.6 billion has been set aside for infrastructure and other capital outlays (out of the PHP 3.4 trillion budget), which accounts for only 71% of the required PHP 1.1 trillion. The 2018 proposed budget has been pitched to reach PHP 3.8 trillion, a 14.6% increment from 2017. Out of this only 25.4%, or approximately PHP 965.2 billion, has been set aside for infrastructure and capital outlays. Assuming that infrastructure spend is levelled out over the five year period, this falls short by approximately PHP 135 billion (in 2018F). Moreover, the Senate and the Department of Finance are currently in disagreement over tax reforms in the country. The tax reform bill passed by the Senate in May 2017 will increase the government’s tax revenue by PHP 1.2 trillion over 2018F-22F from what was originally budgeted. However, this is 8% lower than the tax reform plan proposed by the Finance Department. This additional revenue will not be solely utilised on infrastructure, as there are other sectors that require high levels of government support in terms of funding. The Duterte administration has also included the following as priority areas for development (in addition to infrastructure): • Human capital development • Social protection and sustainable livelihood • Peace and order • Agricultural and rural enterprise productivity The recently passed Universal Access to Quality Tertiary Education Act is one example in which government funding will be directed towards an alternative sector. This act requires an additional PHP 50 billion (1.5% of 2018 budget) on average to be spent annually on education. The 2018 budget, however, has been made without making allocations for the above. In addition, the President’s war on drugs, and focus on peace and order, will also require an increase in budget allocation. In addition to the increments seen in the police, military and judiciary budgets in 2017, the government plans on increasing the salaries of the police and the military in 2018F. As per a statement made by the government, policemen’s salaries alone will be increased two-fold, requiring a further PHP 50 billion annually. The addition of these expenses may result in the worsening of the country’s budget deficit, resulting in a further accumulation of government debt. The Philippines witnessed a three-fold increase in its budget deficit in 2016, reaching 2.7% of GDP from 0.9% in 2015, and is anticipated to pass the 3.0% mark in 2017. The current administration has stated that it aims to limit its budget deficit to 3.0% and maintain it at the same level until 2022. The aforementioned projects and the deficit in infrastructure spend alone will require a minimum of PHP 235 billion to be spent annually in addition to the proposed budget in 2018, which, as per our estimates, may cause the budget deficit to reach 4.4% of GDP in 2018F as opposed to the government estimate of 3.0%. Budget Deficit May Rise Beyond Estimate in 2018

Source- by UZABASE

The accumulation of these factors may hinder the government’s plan of relying on tax revenue to fund 66% of infrastructure, with aforementioned PHP 135 billion needing to funded through alternative means. Assuming that the difference between the expected PHP 1.1 billion and the budgeted infrastructure outlay in 2017 and 2018F was funded entirely through foreign loans, ODA contribution has the potential to increase from 23.0%-34.0%. If the same shortage was funded entirely by the private sector, PPP contribution could increase from 26.0%-37.0%. This provides greater opportunities for PPPs and ODAs to increase their involvement in Dutertenomics, while allowing the government to stay on track of its PHP 8.4 trillion end goal. |

|

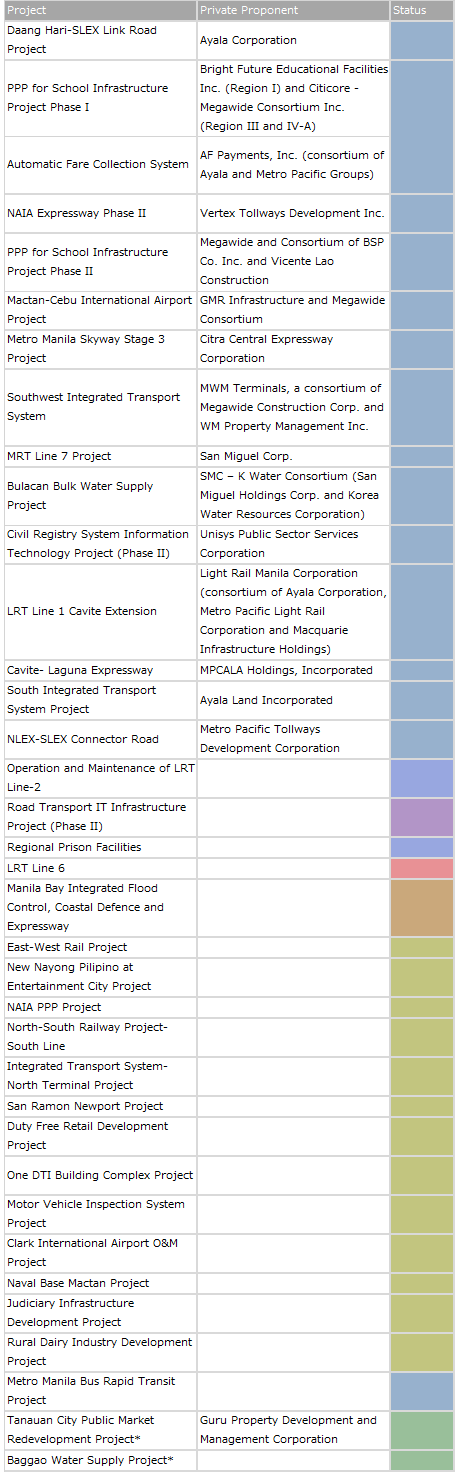

Restructured PPP Framework, A Viable Alternative The Philippines is no stranger to PPPs, with its use of build-operate-transfer (BOT) contracts dating back almost 30 years, where the country was awarded the first BOT contract in Asia in 1988. Subsequently, the Philippines applied a PPP framework to resolve the power crisis the country faced in the 1990s. During this time, PPP projects worth USD 5 billion and a power generation capacity of 4,200 megawatts were commissioned. By 1998, 46% of total power generation came from the private sector, and by 2015 this number had increased to 95%. By 2014 the Philippines’ access to electricity (as a percentage of population) reached 89.1% from 61.8% in 1990. Furthermore, in the late 1990s, the Philippines went ahead to execute the world’s largest water privatisation deal by awarding the Metropolitan Waterworks and Sewerage System franchise to two private entities that engage in water and waste water services (Manila Water Company Inc., and Maynilad Water Services, Inc.), which are still engaged in the provision of water as a utility in the Philippines. Since then, the country’s PPP framework was subject to various challenges, such as having to face the 1997 financial crisis, along with various legal complexities, rendering it ineffective. The weaknesses in the previous PPP framework resulted in the introduction of the prevailing PPP programme in 2010. This new programme, which was recognised by the World Bank in its report titled “Benchmarking Public-Private Partnerships Procurement 2017”, was introduced by the Aquino administration, and is still in use in the Philippines. Under the framework, the government assumes regulatory risk (with a promise to compensate contractors due to a regulatory action which inhibits them from collecting the agreed fee), while commercial risk is to be borne by the private sector. The PPP system is also now open to hybrid structures outside the usual BOT (Build-Operate-Transfer) and BLT (Build-Lease-Transfer) structures. The government has also taken a cue from other countries, and has adopted a more complex bidding system than the previously used ‘lowest bid’, by considering factors such as highest premium offered and lowest viability gap financing (a certain percentage of total capital cost is paid by the government as a grant to make the project economically viable). All of these changes have been made in order to make infrastructure projects more feasible and to attract more private sector investments. There are currently 37 PPP infrastructure projects in the pipeline, out of which 15 had been awarded as of July 2017. These include big ticket projects such as the Line 7 (MRT 7) project and the LRT 1 South (Cavite) Extension Project. (See appendix.) Much interest has been shown by the private sector, both domestic and foreign, towards bidding for PPP projects, with an observable trend of forming consortiums. Since the implementation of this PPP framework, major conglomerates in the country have come together to jointly bid for major projects. One such example would be the forming of Trident Infrastructure and Development Corporation by Aboitiz Equity Ventures, a leading investment holding company, and Ayala Land, a leading real-estate developer in the country. Similarly, Megaworld Corporation and SM Prime Holding came together in 2014 to bid for the Laguna Lakeshore Expressway and Dike Project. The Ayala group is a prominent participant in the PPP programme, being involved in four PPP projects with a total cost of PHP 135.5 billion, and has done so mainly through forming of similar consortiums. The LRT 1 South (Cavite) Extension Project was awarded to a consortium (Light Rail Manila Consortium) made up by Ayala, Metro Pacific Investments Corporation and Macquarie Infrastructure Holdings. Ayala also partnered with three foreign firms in 2016, to bid for the Ninoy Aquino International Airport development project. Under the PPP framework, foreign investments in infrastructure projects is limited to 40%. This has been an improvement from the previous 25% limit set prior to 2010. The forming of such consortiums by well reputed conglomerates have resulted in the PSE relaxing its listing rules for the private proponents of PPP projects. The PSE originally required companies to be profitable for three consecutive years in operation before going public. This requirement no longer exists for companies engaged in PPPs with a minimum project cost of PHP 5 billion. However, a company can seek initial listing only when it has commenced commercial operations on a PPP contract which has a minimum remaining life of 15 years from the date of filing for the listing. Furthermore, in 2016, the Central Bank refined its regulatory guidelines in order to allow companies to participate in PPP project finance activities by structuring as self-contained special purpose entities or consortiums. This allows these companies not to be restricted by the 25% single borrower limit set by banks, as special purpose entities would be considered as independent parties. All these measures provide companies engaging in PPPs with greater opportunities to raise funding. The present government has also encouraged private participation in PPP projects by being open to unsolicited proposals and is in the process of reviewing them for approval. An unsolicited PPP proposal is one in which a private sector company submits a project idea to the implementing agency to develop a public facility. The following conditions need to be met for unsolicited proposals to be considered by the government: • the proposal should involve a new concept or technology and cannot be a part of the list of existing priority projects; • will require no direct guarantee, subsidy or equity from the government; • and should not be a component of an existing approved project. As of February 2017, the DOTr was reviewing an unsolicited proposal for the New Manila International Airport project submitted by San Miguel Corporation, and the DPHW was reviewing an unsolicited proposal for the Manila-Taguig Expressway proposed by Citra Central Expressway Corporation.The government is also considering utilising the PHP 550 million Project Development and Monitoring Facility (PDMF), which was initiated to fund and facilitate pre-investment activities of potential PPP projects, to fund the pre-investment studies for unsolicited proposals as well.However, while the PPP framework has its advantages, and serves as an efficient way to raise funds, it has not been pushed forward as the main source of financing by the current administration. The NEDA has cited delays in awarding of contracts as the main reason for this, as a result of legal complexities behind the bidding process and advanced technical requirements to be fulfilled by the private proponent. During the period 2010-16, only 28 PPP projects were awarded (out of this only 12 were awarded by the Aquino administration). Furthermore, 50% of these projects are yet to be implemented or were terminated as of July 2017. Therefore, it can be established that the way forward for the PPP programme is making its contract awarding process more efficient. This would increase the attractiveness of PPPs as a source of funding, and thereby create better opportunities for private sector involvement in the development of the country. |

|

ODAs Receive Preferential Treatment by the Government Despite its Setbacks The second alternative available, ODAs, are looked upon as a favourable option especially on the back of President Duterte’s strong political connections with East Asia, that has drawn interest from countries such as China, Japan and South Korea into financing infrastructure projects in the Philippines. As of March 2017, 14 infrastructure projects totalling USD 8.8 billion had been lined as possible Japanese investment options, the largest of which was the USD 4.5 billion Mega Manila Subway System. South Korea, on the other hand, is set to finalise USD 1 billion as ODA for the duration of the infrastructure plan. While Japan and South Korea have been significant contributors of foreign aid in the past, China’s involvement has been relatively low. However as of March 2017, China had committed to funds worth USD 3.4 billion to be used to finance at least three infrastructure projects that are expected to be rolled out within 2017. This is in comparison to the USD 115 million given in the form of ODA loans in 2014 (no loans received as ODA from China in 2015). With growing interest from ODA sources, the government has started to shift projects that were being delayed in the PPP pipeline into ODA funded ones. In 2017, two such projects, namely the New Centennial Water Source Kaliwa-Dam Project and the North-South Railway Project-South Line underwent this transferal. China has shown interest in funding both these projects, while Japan has expressed its interest in financing the railway project. The government is also pushing for the implementation of a hybrid PPP system which uses ODAs as a funding tool, with operation and maintenance being handed over to the private sector. This will further take away potential investment opportunities from the private sector. However, while the government is eager to push forward ODAs, past issues related to cost overruns and project delays still remain a concern among industry experts. The ODA-funded Subic-Clark-Tarlac Expressway is one such project which faced both of the issues cited above. The project faced a delay of two years after receiving government approval and took seven years for completion as opposed to the projected five. Furthermore, there was a cost overrun of USD 14. 1 billion making the final project cost amount to USD 32.8 billion, nearly double the approved budget of USD 18.7 billion. The Iloilo International Airport project is another ODA funded project that saw a delay of one year and a cost overrun that resulted in the final cost being 42% higher than what was approved. In retrospect, ODA funded projects faced delays once projects had received approval as opposed to PPPs, which faced delays in the approval process. Furthermore, pushing for ODA funding above the planned 15% will result in a rise in government debt. Growing public debt has not been cited as a major concern by the government due to its expectation of steady economic growth. However, major international institutions such as the World Bank, IMF and ADB have projected the Philippines’ GDP growth to remain within the 6.4%-6.9% range in 2018F and 2019F, lower than the government’s projection of 7.0%-8.0%. Moreover, the Philippines is determined to not see a recurrence of its debt crisis in the 1980s, and as per the Department of Budget and Management (DBM), is focused on pushing down its debt to GDP ratio to 38.1% in 2022F from 40.6% in 2016. This has also been a reason for the government to restrict its infrastructure funding from ODAs, despite growing interest. Moreover, ODAs from China come with unfavourable stipulations in the form of Chinese contractors and labourers tied to these projects. This contradicts the government’s claim that infrastructure projects increase employment opportunities for Filipinos. As per the DBM, job creation is expected to double because of Dutertenomics, with two million jobs expected to be created annually for the duration of the plan, in addition to the average of two million jobs created in the Philippines annually. However, despite these short comings, the Filipino government’s growing political ties with Asia, may result in ODAs being given preference over PPPs in order to finance any gaps that arise in the funding of Dutertenomics. |

|

Appendix PPPs in the Pipeline

Source- Public Private Partnership Centre

*Projects under local government units |