Retail Cross-Border E-Commerce in China: Will New Tax Policies Interfere with the Strong Growth Trajectory?

|

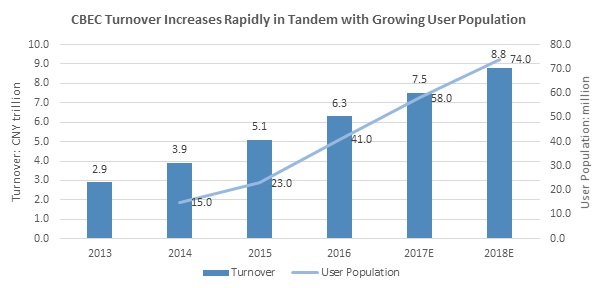

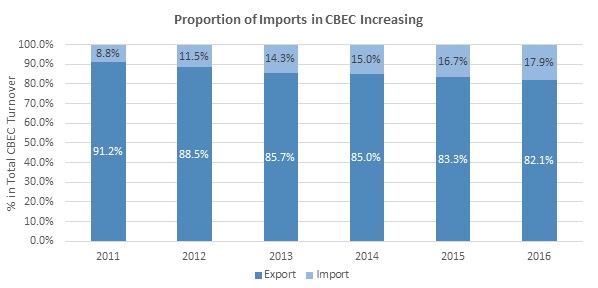

Benefitting from the Internet Era, China’s cross-border e-commerce (CBEC) boomed at a CAGR of 29.5% over 2013–16, reaching CNY 6.3 trillion in turnover (25.9% of total imports and exports and 8.5% of GDP in 2016). The proportion of imported goods rose to 17.9% in 2016 from 8.8% in 2011, indicating Chinese consumers’ increased consumption of foreign imported goods. |

|

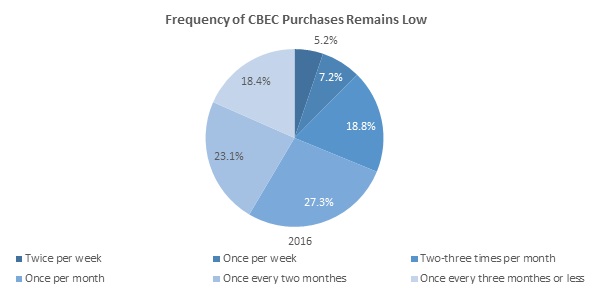

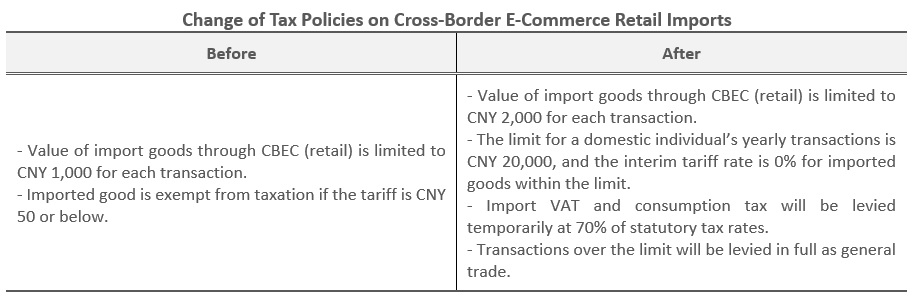

Rising purchasing power, a growing internet population, and rapid growth in support industries (e.g. online payment and logistics) are bolstering the CBEC business’s significant growth. Chinese consumers have developed strong interest in certain categories such as maternal-infant products and cosmetics, and this has boosted demand for these imported goods of better quality and cost performance. Nevertheless, the overall frequency remains low, with only one-third of consumers claiming to make CBEC purchases more than once a month, leaving considerable room for enhancement. In March 2017, the Chinese government promulgated the Tax Policies on Cross-Border E-Commerce Retail Imports, but postponed its implementation until the end of 2018 in order to allow all parties involved to adapt. According to the policy, the government will start to collect value-added tax (VAT) and consumption tax (the rates differ by good) for all parcels arriving through CBEC that currently enjoy a lower parcel tax rate and are exempt from these two taxes. We therefore expect CBEC growth to remain strong under the lower import tariff, but once the new tax policy comes into effect, CBEC expansion should be adversely affected and reduced to a moderate rate. In terms of CBEC players, those who apply the bonded warehouse model will be affected the most, as each and every good will be taxed due to bulk import and customs clearance. Since the majority of players adopt a hybrid between the bonded warehouse model and the direct delivery model, the overall industry will need to face a possible reduction in sales and profit brought about by the coming tax tightening. |

|

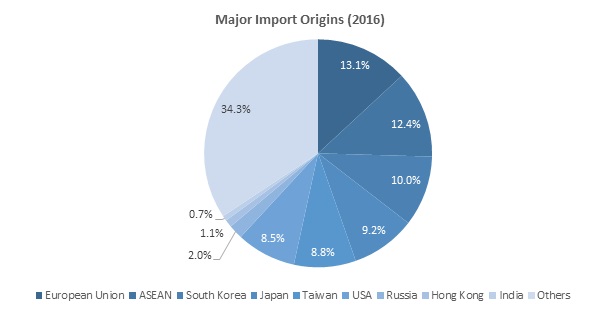

CBEC Up Rapidly in Line with Rising Users Who Demand More Imported Goods as Purchasing Power Strengthens China’s CBEC has become a hot topic in recent years due to its extraordinary expansion. Driven by government policy incentives and people’s growing online shopping activities, total CBEC transaction value, including both B2B and B2C, rose at a CAGR of 29.5% over 2013–16 to CNY 6.3 trillion (around 25.9% of total imports and exports and 8.5% of GDP in 2016). In addition, the number of CBEC users rose to 41.0 million in 2016 (around 3% of the population), almost triple the number in 2014. With increasingly more users adopting CBEC, the industry is likely to continue expanding. iiMedia Research (a local third-party company conducting data analysis and marketing advisory) forecasts that CBEC turnover will amount to CNY 8.8 trillion (11.8% of 2016 GDP) and that the user population will reach 74.0 million in 2018 (5.4% of the 2016 population). Although CBEC remains dominated by exports, especially by B2B exports, a greater share has been shifting towards imports. In 2016, imports accounted for only 17.9% of CBEC total turnover, and exports claimed the remaining 82.1%, compared with 8.8% and 91.2% in 2011, respectively, indicating that people’s stronger buying power is driving up foreign products’ market share in China. Most foreign products are imported from European Union (EU) countries (13.1% of total imports in 2016), ASEAN countries (12.4%), South Korea (10.0%), Japan (9.2%), Taiwan (8.8%), and the USA (8.5%). |

|

Source: iiMedia Research |

|

Source: China E-Commerce Research Centre (100ec.cn) |

|

|

|

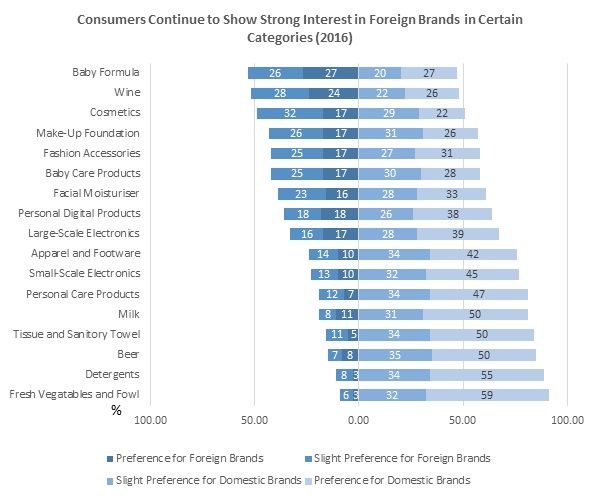

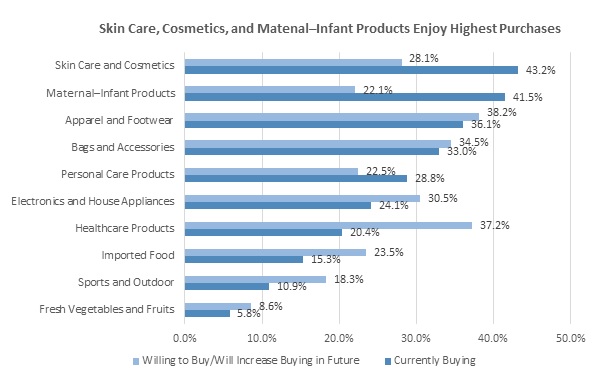

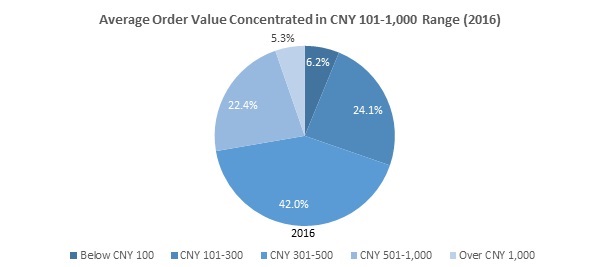

CBEC Purchases Concentrated in Certain Categories and Limited to High-Income Population; Low Shopping Frequency Bodes Well for Volume Growth Most Chinese consumers opt for CBEC due to authenticity, value, and price, as most CBEC retailers guarantee genuineness. Given the prevalence of counterfeit products and the low added-value of domestic goods, people show high preference for foreign brands in certain categories such as baby formula, cosmetics, and fashion accessories. Regional price differences also attract consumers to CBEC. For example, a 50ml Shiseido Ultimune Power Infusing Concentrate costs CNY 860.0 (USD 129.8*) in China, at around a 13% premium to JPY 12,960.0 (USD 114.8) in Japan; Nike Air Force 1 is priced around 25% higher at CNY 749.0 (USD 113.0) in China than in the USA (USD 90.0). As per a survey conducted by iiMedia Research, amongst the large variety of purchases, skin care and cosmetics topped the list in 2016, with 43.2% of respondents claiming to have purchased related products, followed by maternal-infant products (41.5%) and apparel and footwear (36.1%). Some categories showed a gap between current purchases and potential purchases, e.g. only 20.4% respondents purchased healthcare products, while 37.2% said they would be willing to buy or increase the purchase of healthcare products in the future, indicating room for suppliers to fill in. The categories that also present gaps between current and potential purchases include imported food and sports and outdoor equipment. According to iiMedia Research, in-depth internet users with high income tend to become CBEC users. As of 2016, around 73.6% CBEC users in China were female consumers and around 84.0% were aged 19-40. Moreover, around 77.4% users resided in tier-1 and tier-2 cities, of which 45.2% were located in east China regions including Shanghai, Zhejiang, and Jiangsu. Looking at the average order value in 2016, 42.0% fell in the range of CNY 301-500 (≈USD 45-75), 24.1% in the CNY 101-300 range (≈USD 15-44), and 22.1% in the CNY 501-1,000 range (≈USD 76-151). We expect consumer purchases to stay concentrated in these middle-price ranges, as products in these ranges tend to present a larger price difference between products from CBEC and traditional distribution channels. In addition, as people’s spending power increases, consumption is likely to shift gradually towards higher price ranges. Furthermore, more than three-quarters of users shopped less than once a month, and this low frequency of shopping bodes well for future increases. Note: Currency converted at the average rate as of October 2017 as sourced by OANDA.com. |

|

Source: Mckinsey & Company, “Double-clicking on the Chinese consumer” |

|

Source: iiMedia Research |

|

Source: iiMedia Research |

|

Source: iiMedia Research |

|

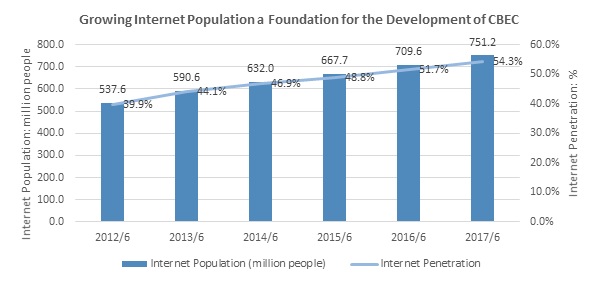

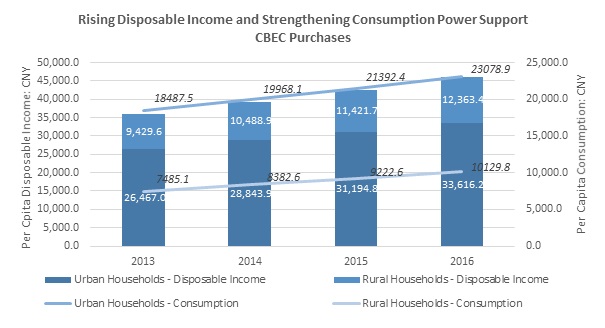

Increasing Penetration of Internet and Online Payments and Improvements in Logistics Support CBEC; Higher Per Capita Income Fuels Purchases The arrival of the Internet Era has bolstered the significant growth in e-commerce to a large extent. As of June 2017, the internet population rose to 751.2 million (a CAGR of 6.9% between June-2012 and June-2017); penetration reached 54.3% at the same time, up 14.4 percentage points from 39.9% in June 2012. However, there remains significant room for improvement when compared with OECD countries such as the USA (88.5%) and Japan (92.0%). The growing application of online payments has also supported the development of CBEC. By June 2017, online payment users numbered 511.0 million (CAGR:22.2% from 187.2 million as of June-2012), around 68.0% of the internet population. In addition, the significant growth in the logistics industry in terms of efficiency and geographical coverage also supports CBEC. As of 2016, logistics costs amounted to CNY 11.1 trillion, i.e. 14.9% of China’s GDP, higher than the USA’s at 8.0% in 2015. China’s spending power has strengthened considerably as the country gradually shifted towards a consumption-driven economy from an investment-driven economy. Over 2013–16, per capita disposable income for urban and rural households increased at a CAGR of 8.3% and 9.4% to CNY 33,616.2 and CNY 12,363.4 respectively. Overall per capita consumption grew at a CAGR of 7.7% and 10.6%, respectively, to CNY 23,078.9 for urban households (68.7% of disposable income) and to CNY 10,129.8 (81.9%) for rural households. In comparison, the overall consumer price index (CPI) rose only at a CAGR of 1.8%, meaning that Chinese people are spending more than before despite inflation. Moreover, people change their consumption behaviour, so that they might be concerned about the products’ brands and quality rather than choose the cheapest. This upgrade in consumption behaviour fuels their spending on CBEC, which offers a wide range of good-quality and reasonably priced products. |

|

Source: China Internet Network Information Centre |

|

Source: China Statistical Yearbook |

| Foreseeable Tax Policy Tightening Likely to Moderate CBEC Growth, Whilst Shifting Purchasing Structure Towards High-End Products

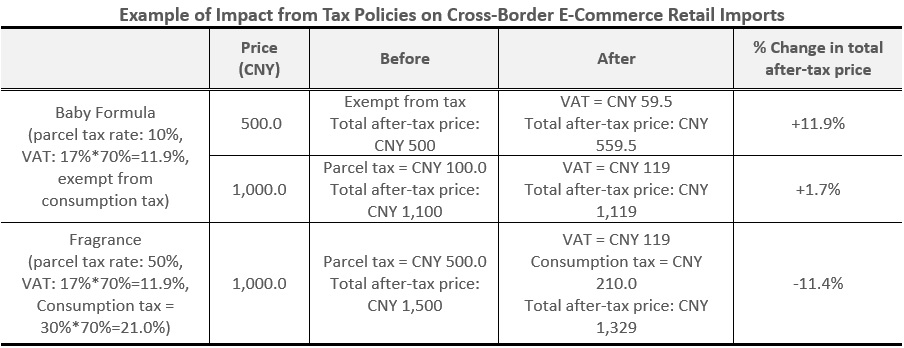

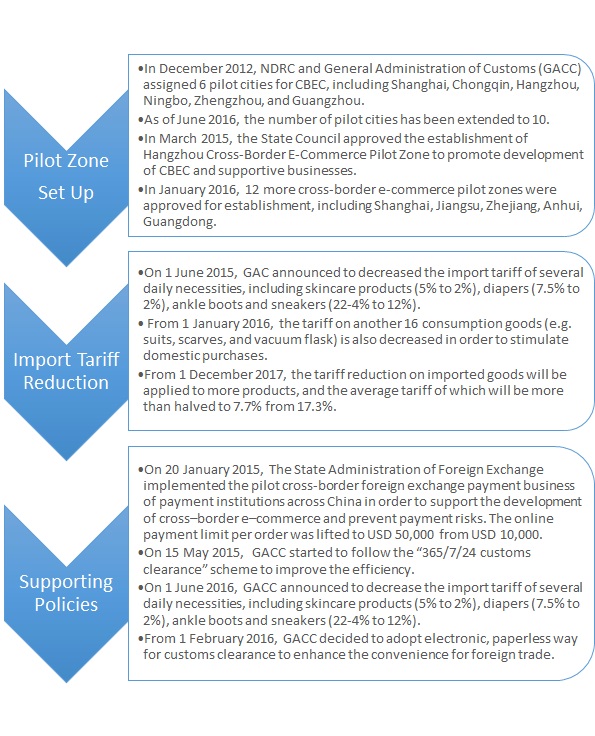

The CBEC industry took off in 2012 when the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) assigned six pilot cities to promote development, such as creating bonded areas. After the CBEC industry enjoyed a growth spurt for several years, the country started to implement new policies to regulate the industry for moderate and sustainable growth. One such policy is the Tax Policies on Cross-Border E-Commerce Retail Imports, published jointly by the Ministry of Finance, the General Administration of Customs, and the State Administration of Taxation; this was rolled out on 24 March 2016 to be effective from 8 April 2016. Shortly after the effective date, the authorities decided to set a transition period until 11 May 2017, in order to give all parties time to adapt and to prevent immediate negative influences such as the heavier-than-expected work load for clearance and taxation and possible sales reduction; the period has been extended twice until the end of 2018. The delayed implementation of the policy is regarded as a positive signal of the government’s supportive attitude towards the CBEC industry. Before the new policy comes into effect, goods imported through CBEC are categorised as personal parcels, enjoy a “parcel tax” rate (exempt from taxation if the tariff is CNY 50 or below), and are exempt from value-added-tax (VAT) and consumption tax. Once the new policies come into effect, they will be treated as commercial products and would be exempt from tariff if the transaction is within the individual quota, which is CNY 2,000 for a single transaction and CNY 20,000 cumulatively per annum. Instead, the government will collect VAT and consumption tax from these imported goods purchased online, which are temporarily set at 70% of the statutory tax rates. Taking baby formula and fragrance as examples, the former’s after-tax price should increase 11.9% and 1.7% respectively after the policy change, assuming the baby formula is priced at CNY 500 and CNY 1,000. In comparison, the after-tax price of a fragrance will be 11.4% less than before, assuming a before-tax price of CNY 1,000. This signals that the government intends to increase tax on low- and mid-priced imported daily necessaries in order to increase its tax income and to foster consumption of domestic substitutes, while reducing tax on high-end products to attract local purchases from overseas shopping for high-end foreign products. Hence, the adjustment will impact many products and could lead to a shift in consumer CBEC purchasing habits towards high-end products in the future. On the other hand, the government has been cutting tariffs on imported goods in accordance with the WTO agreement to further liberalise foreign trade. The tariff reduction also promotes domestic consumption and favours CBEC. The import tariff on daily necessities and consumption goods such as diapers, apparel, and shoes has been halved over 2015–16. In December 2017, the tariff on more goods, including healthcare products and household appliances, will also be reduced. In addition, to cater to the growing consumption of imported goods, the government has introduced supporting policies regarding online payments and customs’ workflow. In brief, we expect China’s CBEC industry to continue to expand under the lower import tariff, but at a moderate growth rate, as the VAT and consumption tax policies should be implemented in the near future. |

|

|

|

|

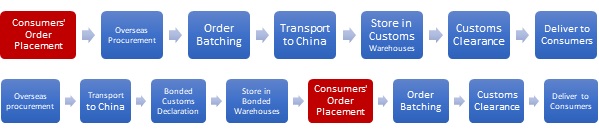

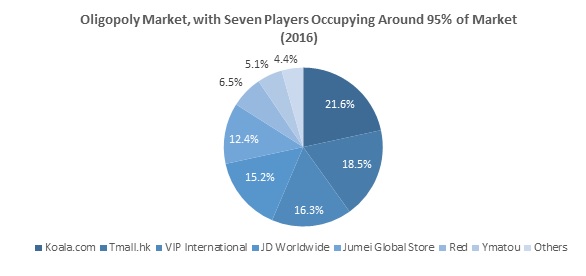

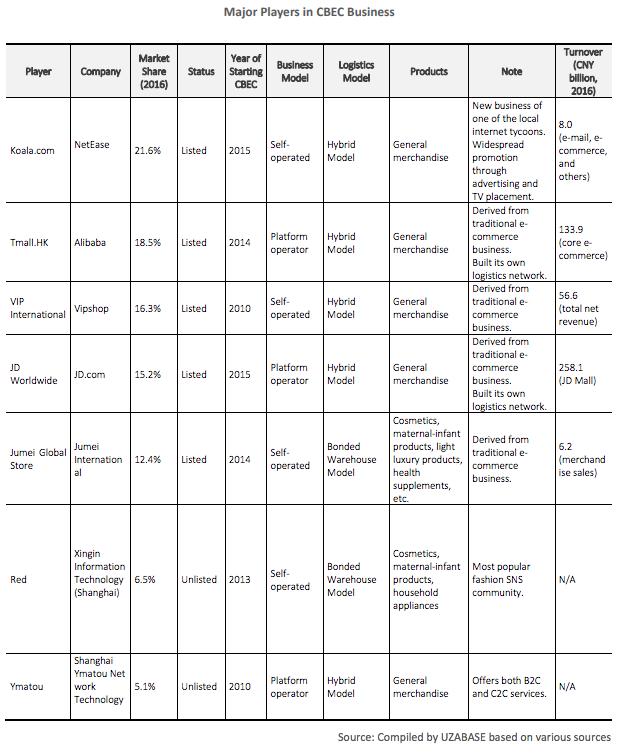

Self-Operated Retailers Hold Large Share of Highly Concentrated Market; Future Tax Tightening Poses Challenge for Bonded Warehouse Model As per the Ministry of Commerce, more than 200,000 companies are currently involved in CBEC, 5,000 of which are platform operators. Despite the large number of participants, the market was dominated by seven players in 2016, namely Koala.com (21.6%), Tmall.hk (18.5%), VIP International (16.0%), JD Worldwide (15.2%), Jumei Global Store (12.4%), Red (6.2%), and Ymatou (5.0%), while smaller players together held 4.4% of the market. Currently, CBEC retailers can be categorised mainly as self-operated retailers (e.g. Kaola.com and Jumei Global Store), which usually engage in procurement, logistics, and payment themselves. CBEC platform operators (e.g. Tmall.hk and JD Worldwide) provide support services to B2B or B2C business tenants. Based on the seven players’ business model, self-operated retailers claimed 56.8% of market in 2016, while platform operators accounted for 38.8%. Both business models will need to source the supply of the goods from manufacturers or wholesalers, and may apply third-party logistics and payment services such as express delivery and Alipay. Self-operated retailers have to handle product procurement and all pre-sale and after-sale services, and this could lead to higher costs of operation. By comparison, platform operators are responsible for running and supervising the websites and have limited involvement in sales activities. The two most common logistics models for CBEC are the overseas direct delivery model and the bonded warehouse model. The former is straightforward and less costly: the company procures the designated goods on behalf of the consumers once they place their orders, and the goods are delivered directly to the consumers after customs clearance. The latter involves more processes, but largely decreases the lead time from consumers’ order placement to final delivery by importing the products in bulk and storing them in bonded warehouses in advance. Due to the longer logistics chain, the bonded warehouse model poses a challenge for the company in selecting best-sellers and maintaining sufficient capital turnover. In addition, this model is costlier due to the additional intermediaries and prepaid expenses. Currently, most top players adopt a hybrid between the two models for suitable products in order to improve competitiveness. The new tax policies will have a higher impact on the players that apply the bonded warehouse model. This is due to their importing and clearing customs in bulk, which means each and every good will be taxed after the implementation, as opposed to sampling examination and taxation for direct delivery parcels. During the one-month effective period during April–May 2016, the players, such as Koala.com, offered discounts or subsidiaries at the cost of their profits, to ensure that consumers can purchase goods at the same price as before, so that sales volumes could be maintained. However, in the long run, the higher after-tax price for low- and mid-priced products (accounting for almost three-quarters of current purchases, as mentioned earlier) will decrease sales. The table below shows the top seven players applying either the hybrid model (bonded warehouse and direct delivery model) or the bonded warehouse model. Therefore, we can conclude again that the new tax policy will adversely affect the overall CBEC industry when implemented. In June 2015, the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology removed the 50.0% ownership cap for foreign telecommunication companies’ e-commerce business. Hence, foreign companies can participate in CBEC as a controlling party, either by creating its own e-commerce website or by supplying goods to existing local platforms. However, based on the current situation where the market is dominated by domestic tycoons, creating a brand new CBEC website can be formidable and costly. Overseas Direct Delivery Model vs. Bonded Warehouse Model |

|

Source: iiMedia Research |

|

|

|

|