Post GE14: What Lies Ahead For Malaysia?

|

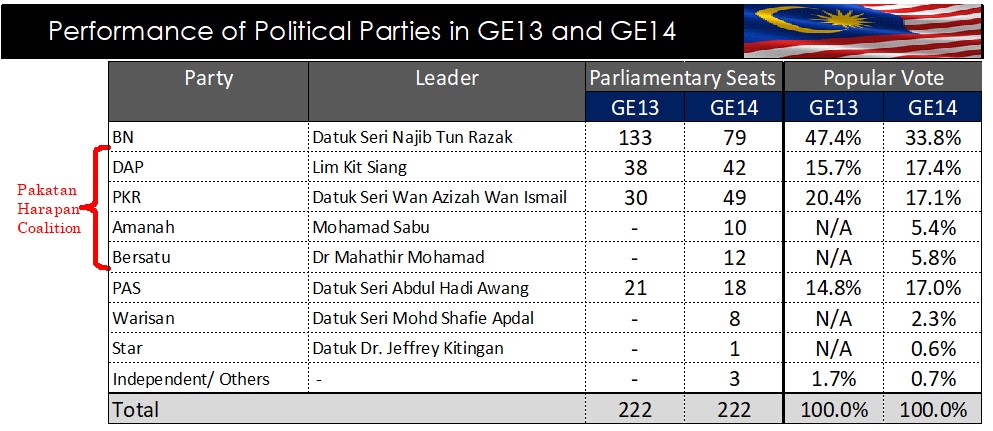

It has been an eventful month for Malaysians, following the victory of the opposition Pakatan Harapan (i.e. Alliance of Hope) party, a coalition led by 92-year old former Prime Minister Tun Dr. Mahathir Mohamad in the 14th General Election. Securing 113 of the 222 parliamentary seats, Pakatan Harapan’s resounding victory was not the outcome expected by many, and especially for the incumbent Barisan Nasional (National Front) coalition. |

|

Members of the United Malays National Organization (UMNO), the bedrock of Barisan Nasional, were left reeling following the results of the GE14. Barisan Nasional’s popular vote margins slipped further; And while describing this development as a “Malay Tsunami” may have been an exaggeration, a larger portion of the Malay electorates have turned the tide against Barisan Nasional. |

|

|

|

What has Changed Since GE13? |

|

Malay voters have traditionally been wary of the opposition parties, particularly concerned that the issues of “Malay rights” are not the chief priorities for these parties. Though ironic, the reappearance of Mahathir Mohamad to head the same parties that he has formerly sought to discredit was a key move to reassure Malay voters to swing to the opposition. As a former founding member and strongman of UMNO, Mahathir Mohamad’s history, legacy and opinions have firmly ensconced him as a trusted champion of “Malay rights”. In another twist of irony, Tun Mahathir Mohamad is now also a partner of opposition leader, Anwar Ibrahim, a man whom he had a falling out with in 1999 and had subsequently put in jail on a controversial sodomy conviction. Anwar Ibrahim has announced that he is in no hurry to replace Mahathir Mohamad, but it is still too early to tell if this truce can percolate into a more stable partnership between the now two largest characters in Malaysian Politics. |

|

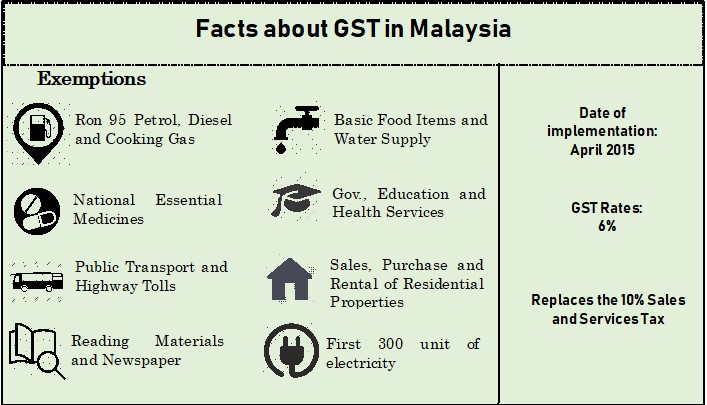

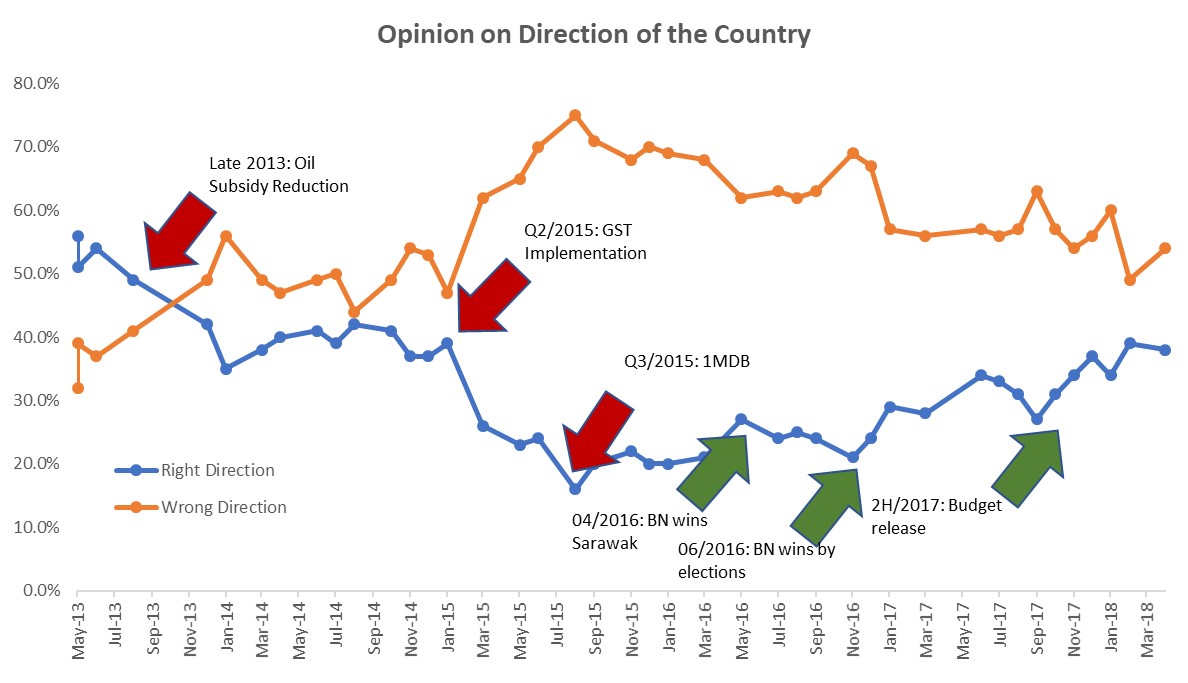

Pre-election surveys by Merdeka Center, a think tank organization, suggests that much of the causality can be pinned down to “bread and butter” issues, namely rising costs of living, which many ordinary Malaysians squarely blame on reduction of oil subsidies and the implementation of the Goods and Services Tax (GST). The majority of those surveyed saw the rollback of oil subsidies in late 2013 the point when the country started heading in the “wrong direction”, exacerbated by implementation of GST in Q2 2015. The introduction of GST meant that instead of only the top 20% of income earners having to pay taxes (in the form of income taxes), everyone else will have less spending power on their disposable income. According to a professor at the ISEAS Yushof Ishak Institute, the lower middle especially which will now be paying taxes for the first time, will be the hardest hit, as about 30% of this groups household items are not exempted from GST. |

|

|

|

Source: Budget 2015, Malay Mail |

|

While issues of corruption, cronyism and race equality has been foremost and perennial in the minds of Malaysians in urban centers of Selangor and Penang, the experience of previous general elections has shown that this has not translated into a call-to-action for the Malay-Muslim majority. The 1MDB scandal, however, has become a turning point for voters, in GE14, even amongst the perceptibly BN-stalwarts in the civil service. For the latter, the far-reaching fallout from the 1MDB scandals has become an issue of national pride. |

|

Survey Indicates that Malaysians believe the country is moving in the Wrong Direction Since Fuel Subsidy Cuts, GST Implementation and 1MDB Scandal |

|

|

|

Source: Merdeka Center, based on surveys conducted in Peninsular Malaysia |

|

Federal Government Fiscal Deficit to Widen in 2018 |

|

Unsurprisingly, it can be said that Pakatan Harapan’s manifesto, particularly its “10 Promises in 100 Days”, focuses squarely on these three issues. Under this action plan, the party sets out to achieve the following within 100 days of the election: |

|

• Abolish the 6% Goods and Service Tax; • Reintroduce targeted fuel subsidies; • Review mega projects awarded to foreign companies; • To investigate institutions implicated in scandals, namely 1MDB, FELDA, MARA or People’s Trust Council, and Tabung Haji or Pilgrim Fund Board; • Standardize and increase minimum wages;Survey • Postponement of repayment to the National Higher Education Fund for debtors earning below RM4,000 per month; • Introduce Employees Provident Fund scheme for housewives; • Set up Special Task Force to execute the 1963 Malaysia Agreement on the autonomy of Sabah and Sarawak; • Introduce Skim “Peduli Sihat” or a national healthcare assistance initiative; and • Abolish debt of Felda’s settlers; |

|

Some of these policies have been criticized as being populist and unsustainable, and perhaps to outside observers, the abolishment of GST counts as amongst the most controversial. In the month following his appointment as the country’s seventh Prime Minister, Mahathir Mohamad has swiftly moved to address the GST issue, much to the joy of ordinary citizens, but to the worry of investors and economists. Mahathir Mohamad has sought to allay some of those fears, by recruiting former Bank Negara Malaysia governor, Tan Sri Dr. Zeti Akhtar Aziz as a senior government advisor. Subsequently, Zeti confidently declared that Malaysia will still be able to meet its revenue requirements without GST, by “prioritizing projects”, increasing efficiency of the public sector, avoiding wastage and exploring new sources of revenue. On 1 June 2018, Malaysia officially set GST rates to zero, thereby reversing the unpopular tax and fulfilling a core tenet of their election promise. |

|

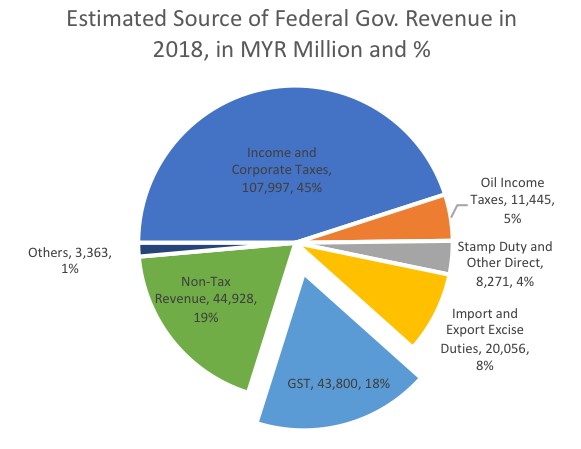

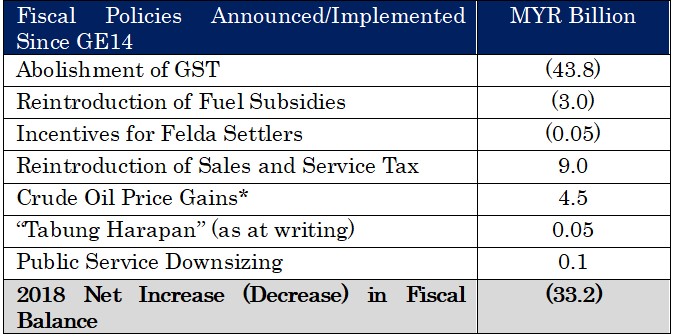

Prior to the election, it was estimated that GST will contribute about MYR 43.8 billion or 18% of the Federal Government’s revenue in 2018, second largest tax revenue component after income and corporate taxes. Herein lies the biggest challenge for the new government, either to come up with a diverse mix of alternative revenue source or reduce fiscal expenditure. Already, Mahathir Mohamad told reporters that “We find that the (fiscal) situation is worse than we thought when we were preparing the manifesto. That’s why the promises will be fulfilled, but they must take into account the financial situation.” |

|

|

|

Source: Malaysia Ministry of Finance |

|

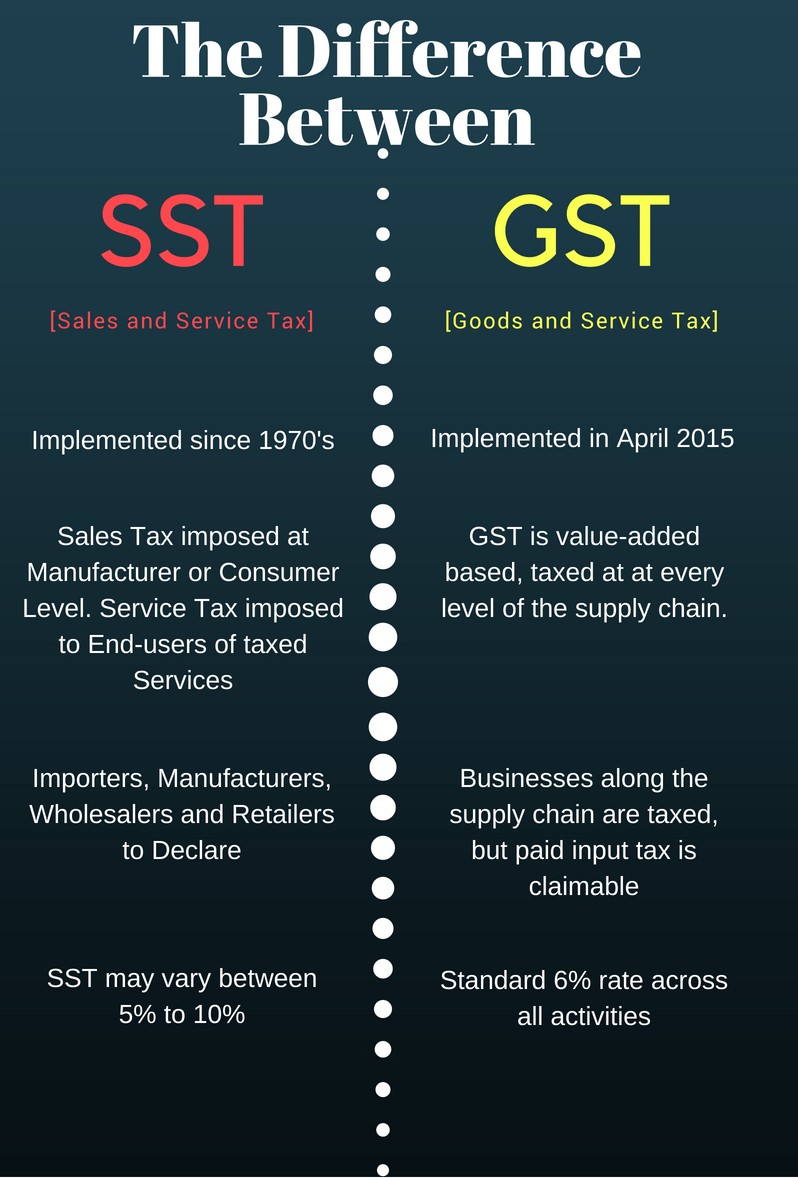

Pakatan Harapan’s manifesto suggests that the narrower based Sales and Service Tax (SST) can replace GST to offset revenue loss from “zerorising” GST. Mahathir Mohamad has hinted SST will be making a return in September 2018 and his administration is currently ruminating on a 10% sales tax. There is a cloud of uncertainty over what will be covered under the ‘new’ SST and how will be implemented, but the impact of SST on inflation for the lower income group should not be any different from GST, as most essential goods were already zero-rated under GST regime. |

|

A reboot of the 10% sales tax prior GST may only plug in less than half of gap left by GST removal, and that is not even factoring in the three to four months “tax holiday” for consumers, between May and September 2018. This runs in contrasts against a more optimistic projection by Tun Daim Zainuddin that the SST will rake in RM 30 billion in revenue. Back in 2014, sales tax contributed about MYR 11.0 billion to the coffers, and we estimate that it might have been contributing to between MYR 14 and MYR 15 billion in 2018, less than 40% of the MYR 43.8 billion contribution from GST. The Service Tax should account for another 25% to 27%. Realistically however, and with the tax “holiday”, an optimistic projection for the Sales and Service Tax may cover only about 20% to 25% from the gap left by GST revenue for this year. In addition, the SST is susceptible to cascading tax, double tax, tax erosion and leakages through transfer pricing. The old SST targets mostly durable goods, which means that prices of automobiles, furniture and household appliance will likely rise by the start of 2019. |

|

|

|

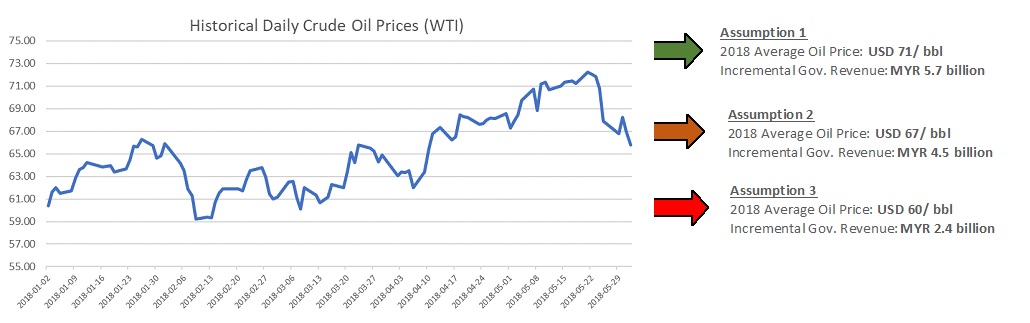

The new Ministry of Finance, under former Penang Chief Minister Lim Guan Eng, issued a statement saying that rising global oil prices may provide fiscal space. Earlier estimates from the Ministry indicates that corporate taxes from petroleum companies will bring in a net revenue of MYR 37.8 billion (including petroleum income tax, royalties and ancillary income from Petroliam Nasional Bhd,) assuming an average crude oil price of USD 52 per barrel in 2018. |

|

Following the bullish run in 2Q 2018, market analysts are still divided on how crude oil prices will turn out for the rest of the year. The US EIA predicts oil prices to rally between USD 66 to USD 71 per barrel, but others like Barclays, see a potential price correction late 2018, after the rally in 2Q. According to second finance minister, Johari Abdul Ghani, for every US$1 per barrel increase in global oil price, the government’s revenue would increase by around MYR 300 million (about USD 70 million) a year. Assuming a sustained rally of oil prices at about USD 67 per barrel for the rest of the year, the government can expect a net additional revenue of RM 4.5 billion. However, oil prices will most likely fluctuate this year and the next, and most observers have cautioned against taking the optimistic stance that oil prices rally to significantly plug the revenue gap. |

|

|

|

Source: Compiled by UZABASE |

|

Meanwhile, the government announced in early June that it has committed MYR 3 billion to finance fuel subsidies until the end of 2018. The amount will be used to keep RON95 gasoline and diesel to a fixed price of MYR 2.20 a liter and MYR 2.18 per liter respectively, while RON97 will be floated on a weekly basis. In the first week of its introduction, the subsidy will cost about MYR 0.33 per liter for the subsidized fuel categories. Economists had said that any potential increase in subsidy costs from further rise in oil prices will be cushioned by higher petroleum receipts. Mahathir Mohamad have also announced a “Hari Raya” incentive for Felda settlers which will add another RM 50 million to the federal government’s expense. Under this program, qualified Felda settlers will receive RM 450 each. |

|

On the other hand, Lim Guan Eng has expressed hope at recovering the USD 4.5 billion (about MYR 18 billion) worth of assets that was siphoned off from the accounts of 1MDB. The main challenge facing his ministry is in tracking down the global money trail, and the new Finance minister had termed the likelihood of recovering those assets as “a billion-dollar question”. As at this moment, investigations are being re-opened but recovering those assets will be a long drawn out process. The government is also downsizing the public sector and closing down agencies which it deemed redundant. Some of those destined for the “chopping board” includes SPAD, Special Affairs Department and National Council of Professors, which can free up an estimated additional MYR 0.1 billion of funds. |

|

The federal government fiscal deficit is expected to widen by a further MYR 33.2 billion or equivalent to almost 100% of the earlier projected deficit of MYR 39.8 billion. By just taking into account the announced or implemented fiscal policies to date, the deficit will sum up to MYR 73.1 billion. |

|

|

|

*Assuming USD 60/bbl Annual average price |

|

Failure to Reign In Fiscal Deficit Will Likely Lead to Curtailment of Reform Agenda |

|

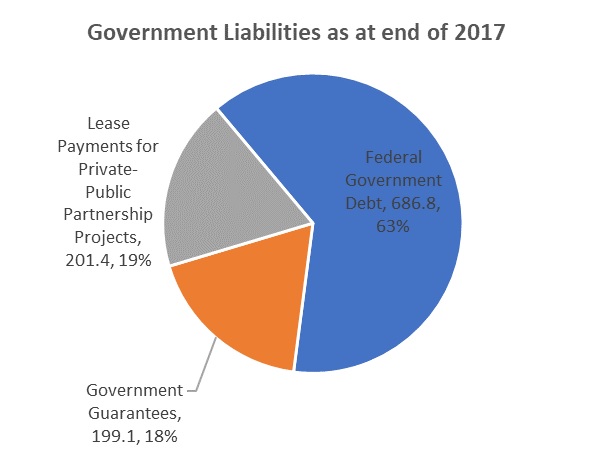

The widening fiscal deficit will put mounting pressure on the government’s reform agenda, on top of the already escalating issue of government liabilities. Lim Guan Eng recently announced that government liabilities have exceeded MYR 1 trillion as of end 2017, as opposed to the MYR 686,6 billion previously declared by Najib Razak’s administration. However, it should be noted that Lim Guan Eng’s methodology is not the existing global standard to calculate government debt. The difference comprises of contingent liabilities including government guarantees MYR 42.2 billion ringgit for Danainfra Nasional Bhd, MYR 26.6 billion for Prasarana Malaysia Bhd and MYR 38 billion ringgit for 1MDB. On top of that, the government is liable for payments for public-private projects of MYR 201.4 billion. Analyst and credit rating agencies have, at start of 2018, raised concerns over the possibility of ballooning contingent liabilities taken on by the government. However, Najib Razak had earlier in November 2017, declared that the government has contingent liabilities in excess of MYR 200 billion to four statutory bodies and 26 firms under the Minister of Finance Inc, for “high-impact” projects. |

|

|

|

Source: Ministry of Finance Malaysia |

|

The most direct impact of this revelation will be in the bonds market, with high chance of increased borrowing costs amidst a slew of maturing sovereign bonds scheduled in second half of 2018. Any ratings downgrade may prompt a reduction in foreign holdings of government, which stood at about 30% last year. The impact of government debt on the country’s economic growth is however, uncertain, as existing studies do not point to anything conclusive. Any prognosis will boil down to how much of those actual and contingent liabilities are economically productive. Debt incurred for investments spending with significant multiplier effect on the economy must be retained while leakages and transfer payments should be minimized. The new government have initiated the process of reviewing mega projects, including the Kuala Lumpur – Singapore High Speed Railway project, but any further significant increase in government debt may prompt Mahathir Mohamad and Lim Guan Eng to take a more aggressive stance with regards to cancelling some of the more productive infrastructural projects. |

|

Removing GST Not the Silver Bullet to Rising Cost of Living |

|

Official data from Royal Malaysian Customs and the Finance Ministry claims that with exemptions on essential goods, GST is not a regressive tax regime. It was calculated that the tax burden, as percentage to expenditure, for a low-income household with an income of MYR 2,000 is only 2.6% and in contrast, the ratio of tax to expense for an upper middle class with a household income of MYR 12,000 is 4.14%. The tax incidence on expenditure for a household with monthly income MYR 2,000 is RM39.16 per month whereas for a household income of MYR 12,000 is MYR 345.06 per month. Furthermore, the low-income household spends about 32% of its total expenditure on zero-rated item and 32.63% on items subject to GST where else a household income of RM12,000 spends about 12.15% of his total expenditure on zero-rated item and 63.90% on items subject to GST. |

|

Studies have shown that inflation in Malaysia has also been historically strongly related to more fundamental factors, like interest rates and money supply amongst others. A Bank Negara Malaysia paper has noted a 10% depreciation can result in between 0.2% to 0.6% inflation, but that exchange pass through can be higher during sustained periods of MYR depreciation; And the MYR has depreciated significantly since 2013. The root problem of inflation, will not be absolved just by the abolishment of GST alone, and we believe that any reversal of inflation post-GST will be short-lived, with all else being constant. |

|

Depreciation of MYR in Recent Years, and Not GST Alone, May Have Been a Key Contributing Factor to Higher Costs of Living for Malaysia |

|

|

|

Source: Trading Economics, Department of Statistics Malaysia, ST Louis Federal Reserve |

|

Crucial for New Government to Refocus from Low Hanging Targets and on into Deeper Reforms |

|

2018 will undoubtedly be a tough year for Mahathir Mohamad’s new government, but there is a question on whether over-posturing have also started to box in the administration into this unenviable situation. For example, Pakatan Harapan’s election victory, may not have been entirely unexpected, given that the opposition have been closing the gap in popular votes since GE12. Whereas, the battleground in the previous General Elections have been drawn on usually local and isolated issues, the 1MDB scandal may have proved to be “straw that broke the camel’s” back. In hindsight, it may have been sufficient for the new government propose a credible but realistic plan in its manifesto, to remove Najib Razak from power, and let the fall-out from 1MDB scandal to tip the balance in their favour. |

|

It remains to be seen whether the new government will put into place more robust and comprehensive reforms to root out institutionalized corruption, rather than just replacing Barisan Nasional’s government officials and ministers with their own. The new government needs to close regulatory loopholes, and should do so while it still has significant political capital. While the new government have been swift to implement fiscal policies to appease the electorate, detailed announcements on deep-set measures to enforce transparency and accountability in public service and political institutions have been less forthcoming. The current leaders will also have to signal a concerted intent to stamp out cronyism even within their ranks, and this will include full disclosure and the quick conclusion over Lim Guan Eng’s graft trial. Otherwise, there is a risk that Pakatan Harapan or its successors may turn into “Barisan Nasional 2.0”. |