Are Governments Ill-Equipped to Face the Challenges of a Rapidly Ageing Society in the Asia Pacific?

|

Population ageing is occurring on a global scale, with virtually every country in the world experiencing growth in ageing both in terms of numbers and proportions. The Asia-Pacific region (APAC), home to the world’s largest ageing population (2015), is the spotlight of this story. |

|

According to the UN, the number of elderly people in the APAC is expected to grow at a CAGR of 2.6% over 2015-50E to approximately 1.3 billion people by 2050E from 0.50 billion people in 2015 (57.4%), and continue to account for the majority of the global elderly population by 2050E (61.8%). This trend is underpinned by the rapid pace of ageing in many APAC countries, many still in the developing phase. The trend has been supported largely by declining fertility levels across countries, coupled with higher life expectancy owing to improving living standards, healthcare, and better nutrition, among other factors. The populations of major economies such as China and India have begun to age before those countries achieved high-income status, and this is an ongoing cause for concern. |

|

The demographic transition towards an ageing society has deep social, economic, and political implications for the region, with most governments having to bear the burden of providing adequate social security and healthcare. However, based on our analysis, most APAC countries, especially in Southern Asia, suffer from inadequate pension coverage, while also being burdened by high out-of-pocket expenditure for healthcare. Our analysis goes on to conclude that, despite this phenomenon, some countries such as China and India seemed to have factored in the ageing crisis into their budgetary expenditure in the medium to long term. However, others such as Sri Lanka, Nepal, and Bangladesh are likely to struggle with the ageing crisis, given that they face economic headwinds owing to their low-income status. This implies that these countries need to act in the short to medium term in order to overcome the negative implications of an ageing society. |

|

APAC Has World’s Largest Ageing Population; Pace of Ageing a Cause for Concern |

|

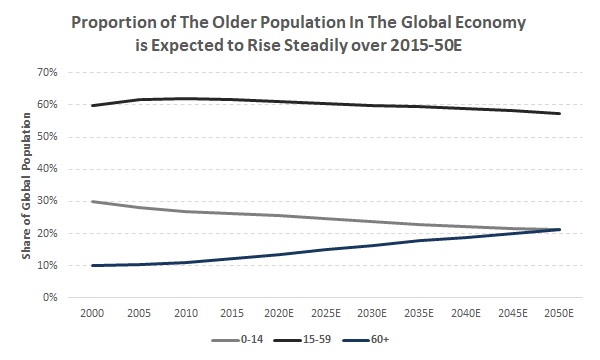

Most countries around the world are experiencing population ageing — growth in the share of the number of elderly (people above the age of 60) in a country’s population— owing to lower fertility rates and higher life expectancy. As per the UN World Population Ageing Report 2015 and UN World Population Prospects: 2017 Revision, the number of people aged 60 or above globally is expected to more than double to 2.1 billion in 2050E (21.4% of the total global population in 2050E) from 0.9 billion in 2015 (12.2% of the total global population in 2015 [1] ), although the timing and pace of this transition will vary significantly across regions. |

|

[1] Data used in 2015 was revised in 2017 by the UN World Population Prospects. Unless otherwise stated, this holds throughout the report. |

|

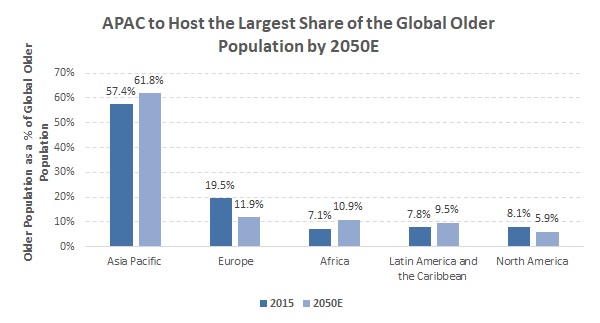

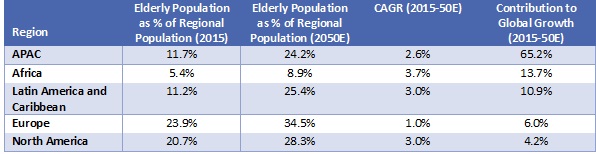

As of 2015, the Asia-Pacific region (APAC) registered the largest ageing population globally, with approximately 520 million people aged 60 and above, accounting for 57.4% of the global elderly population, followed by Europe (19.5%) and North America (8.1%). Based on projections in the UN World Population Ageing Report 2015, the APAC’s elderly population is expected to grow at a CAGR of 2.6% over 2015-50E to approximately 1.3 billion people in 2050E (61.8% of the global elderly population in 2050E); this is faster than the ageing projected for Europe, but slower than that for Africa and Latin America. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

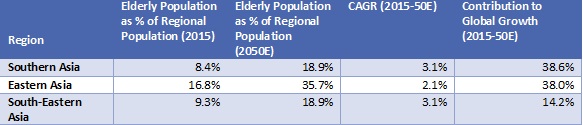

Source: Compiled by UZABASE based on the UN World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision |

|

Note: Table sorted by Contribution to Growth (2015-50E) |

|

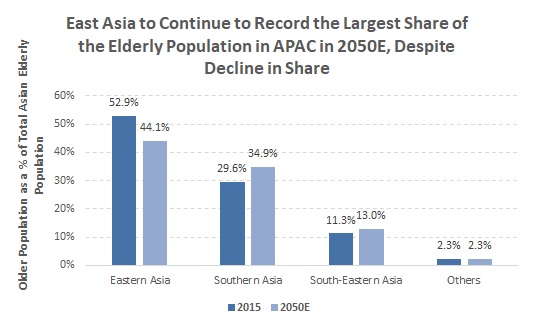

In terms of sub-regions in the APAC, as per the UN World Population Prospects: 2017 Revision, Eastern and Southern Asia together are expected to account for 79.0% of the total Asian elderly population in 2050E, contracting from a cumulative total of 82.5% in 2015. Eastern Asia is home to some of the world’s most aged populations, including Japan, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. As such, the pace of ageing in Eastern Asia is likely to be significantly lower than in all other APAC regions over 2015-50E; moreover, Eastern Asia’s share of the elderly should decline, while others’ increase. |

|

|

|

|

|

Source: Compiled by UZABASE based on the UN World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision |

|

Note: Table sorted by Contribution to Growth (2015-50E) |

|

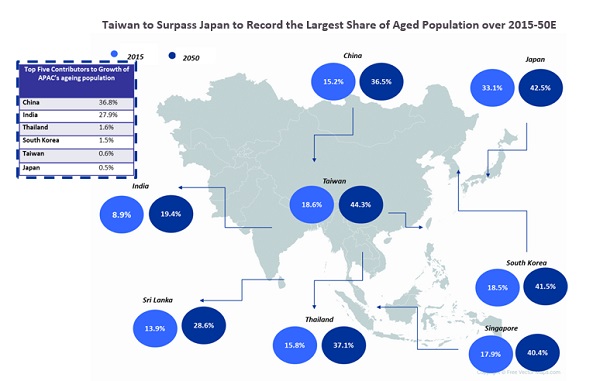

|

|

Source: Created by UZABASE based on map provided by Free Vector Maps.com and data as per the UN World Population Ageing Report 2015 |

|

Steady Decline in Fertility and Increasing Longevity Accelerate Ageing; Major Economies Getting Old Before Getting Rich |

|

Globally, the elderly population is concentrated mostly in less-developed regions (GNI less than USD 1,025), and their elderly populations are growing faster than those in more developed nations (GNI greater than USD 12,475). As of 2015, as per UN World Population Prospects: 2017 Revision, the elderly population in less-developed regions around the world accounted for 67.1% of the total global elderly population. Accordingly, the number of elderly people in less-developed regions is expected to rise at a CAGR of 3.6% over 2015-50E to 1.7 billion (81.0% of the global elderly population) in 2050E from 0.60 billion (66.7% of the global elderly population) in 2015. This contrasts with growth expected for developed regions: a much slower CAGR of 1.3% over 2015-50E to 0.4 billion (19.0% of the global elderly population) in 2050E from 0.3 billion (33.3% of the global elderly population) in 2015. |

|

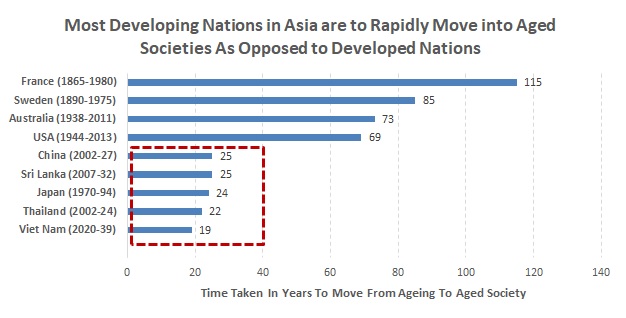

This trend has been supported by a more rapid pace of ageing in developing nations in the APAC than in others; most APAC countries are seen to be moving into ageing/aged societies within a short period of time, as per the UN Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP) in 2016. This implies that these societies are likely to have limited time and opportunity to adjust to the needs of an aged society. |

|

|

|

Source: UN ESCAP, “Ageing in Asia and the Pacific” |

|

The rapid development of ageing amongst these nations has been driven strongly by two key macroeconomic factors: |

| 1. Fertility Decline |

| 2. Increase in Life Expectancy |

|

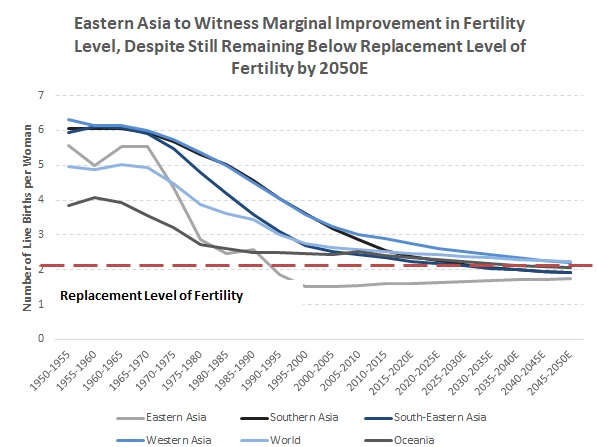

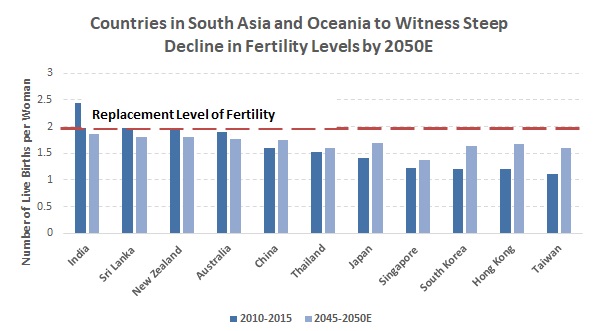

In the APAC, fertility rates — the average number of live births per woman — have declined more rapidly than in other regions (Asia: 2.2 in 2015 versus 5.8 in 1950; Europe: 1.6 in 2015 versus 2.7 in 1950; North America: 1.8 in 2015 versus 3.8 in 1950). In particular, fertility rates have declined more rapidly in Eastern Asia, and this has been largely due to China’s (previous) one-child policy, which lasted for a period of approximately 40 years post 1979. However, with the abandonment of this policy, as per estimates in UN World Population Prospects: 2017 Revision, these levels could rise marginally in the future (1.7 in 2050E from 1.5 in 2015), albeit remaining below the replacement level of fertility (2.1 children per woman), as growth will be slow. On the other hand, other regions (e.g. South Asia) are likely to experience continuous decline below the replacement level of fertility, albeit at a slower pace than that observed in East Asia. |

|

|

|

|

|

Source: UN World Population Prospects: 2017 Revision |

|

Note: Replacement level of fertility refers to the total fertility rate at which a population replaces itself from one generation to the next, without migration |

|

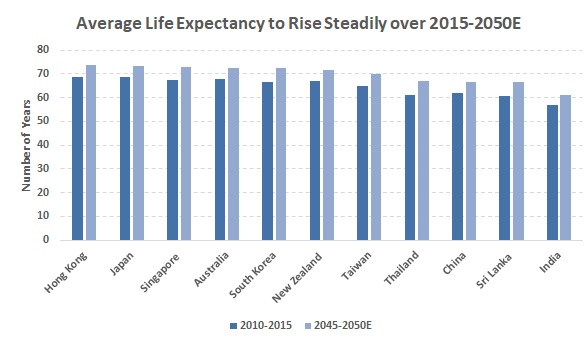

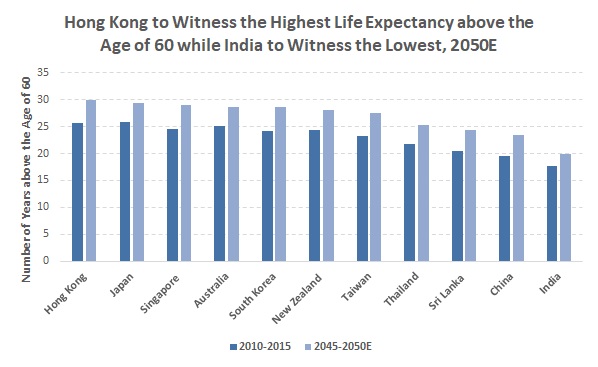

Furthermore, life expectancy in the APAC has trended up due to improved living standards and healthcare, better nutrition, and increased education. According to UN World Population Prospects: 2017 Revision, average life expectancy in less-developed countries rose to 59 years in 2015 from 43 years in 1950, signalling a closure of the gap with developed economies, where it increased to 64 years in 2015 from over 56 years in 1950. In Asia, average life expectancy increased further to 60 years in 2015 from 43 years in 1950, while in Oceania life expectancy rose to 65 years in 2015 from 53 years in 1950. Moreover, in the APAC, life expectancy at age 60 has shown an uptrend, and that is likely to continue. |

|

|

|

|

|

Source: UN World Population Prospects: 2017 Revision |

|

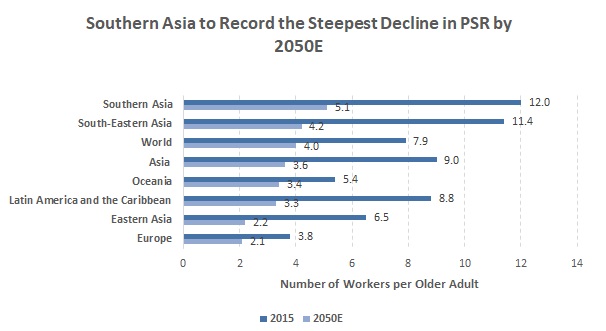

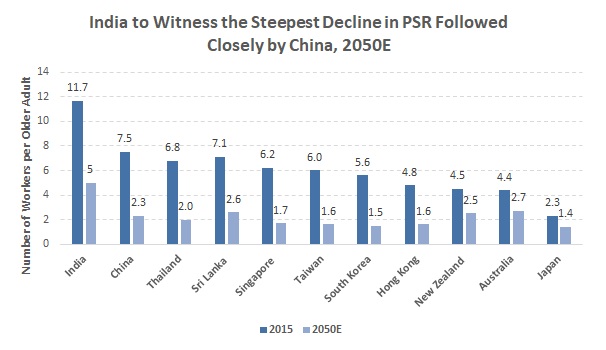

Consequently, declining fertility and rising life expectancy have led to growth in elderly populations in many countries, with fewer children to support/succeed them. This had led to a sharp decline in the potential support ratio (PSR) — the number of persons aged 15-64 years economically supporting each person aged 65 or over. Accordingly, as per projections in UN World Population Prospects: 2017 Revision, the PSR for Asia is projected to fall to 3.6 workers per elderly person in 2050E from 9.0 workers per elderly person in 2015, and that for Oceania to fall to 2.7 workers per elderly person in 2050E from 4.4 workers per elderly person in 2015. |

|

|

|

|

|

Source: UN World Population Prospects: 2017 Revision |

|

Note: PSR is a weighted average calculation |

|

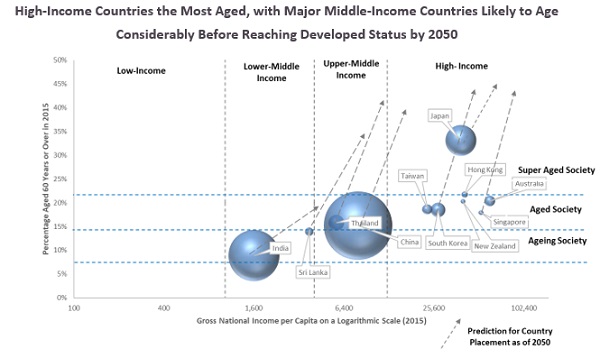

Although it is common to associate countries with higher incomes with a more advanced stage of ageing, several outliers were observed in the APAC, where economies are growing older before reaching high-income status. For instance, India and China, with GNI per capita of USD 1,600 and USD 7,940 in 2015, respectively, was home to a proportion of elderly people in the range of 8-15%, and are therefore classified as ageing. This was in contrast to countries such as Japan, which had both high-income and super-aged statuses. The rapid pace of ageing consequently implies that the changing demographic structure could pose significant developmental challenges to economies such as India, China, and Thailand, which are ageing before being classified as developed nations, in contrast to countries such as Japan, where the state can bear the burden of an ageing society, as they have already reached developed-country status. |

|

|

|

Source Compiled by UZABASE based on the UN World Population Ageing Report 2015, World Bank GNI per Capita —Atlas Method and Taiwan “National Statistics”; Forecasts for 2050 – by UZABASE based on HSBC “The Consumer in 2050” and the UN World Population Ageing Report 2015 |

|

Note 1: Bubble size represents size of older population as of 2015 |

|

Note 2: Ageing society has a proportion of 7–14 % older persons; aged society: 14–21%; super-aged: above 21% |

|

Low Pension Coverage and High Out-of-Pocket Healthcare Expenditure to Challenge Rapidly Ageing Low-Middle-Income Countries |

|

As discussed above, the APAC is challenged critically by a rapidly ageing society. Given the heterogeneity of the region, no single strategy can address the problem of ageing for all countries uniformly. In fact, there exists many different interlinked macroeconomic and societal factors that make the process of ageing complex. |

|

|

|

Source: Re-created by UZABASE based on Marsh and McLennan Companies, “Advancing into the Golden Years: Cost of Healthcare for Asia Pacific’s Elderly” |

|

We focus on two key risks that are likely to continue to challenge the APAC due to population ageing: |

| 1. Pension and Social Security |

| 2. Health of the Elderly |

|

|

As discussed previously, the PSR across the APAC is expected to follow a downward trajectory. However, in most Asian countries, it is customary for ageing parents to rely on family for support — both financial and moral. Nevertheless, as PSRs continue to decline, there will be fewer family members of working age to undertake such responsibility. This means that falling PSRs are likely to impact existing social security schemes, pay-as-you-go pension systems in particular, where contributions paid by existing workers support the pensions of retirees. |

|

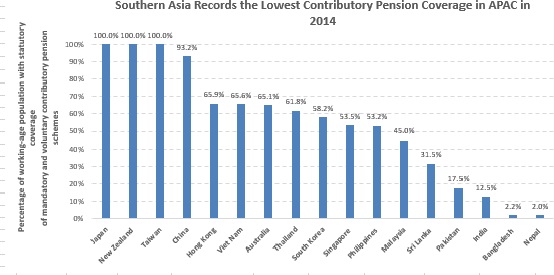

In general, coverage of contributory pensions (mandatory or voluntary schemes) remains low in APAC countries, but with sub-regional differences. As per the International Labour Organization (ILO), coverage was found to be relatively healthy in regions of North, Central, and East Asia, while it was relatively low in South-East Asia and even lower in South Asia. For instance, as of 2014 (latest available data), less than a third of the working-age population was covered by a contributory pension scheme in Bangladesh, India, Nepal, and Sri Lanka. In some cases, the shortfall was explained by the following: |

| 1. The non-existence of mandated pension plans for private workers (examples include Cambodia and Myanmar) |

| 2. Poor collection and enforcement of pension mandates (example include Indonesia) |

|

|

Source: ILO, “World Social Protection Report —2014/15” |

|

Note: Latest available data is for 2014 |

|

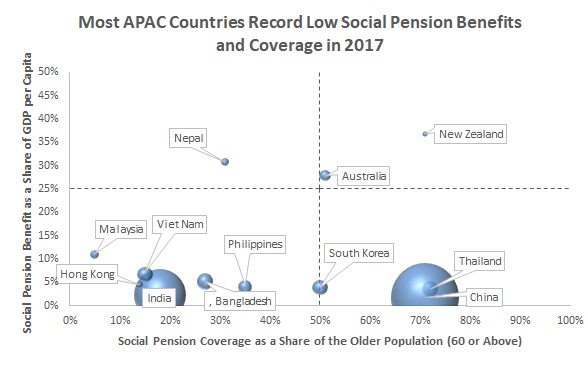

Given inadequate access to contributory pension schemes, most elderly people seek out social pension benefits (non-contributory pensions, i.e. cash transfers that governments grant to the elderly, where eligibility is independent of past contributions/earnings) for basic income. However, most countries struggle to balance coverage with benefits, with countries maximising coverage at the expense of benefit levels. Nevertheless, a low benefit level is still preferred by most elderly people who live in areas of high poverty, where they require some form of financial relief. |

|

|

|

Source: HelpAge International, “Social Pension Database”, UN World Population Ageing Report 2015 |

|

Note: Bubble size represents size of elderly population in 2015 (revised in 2017) |

|

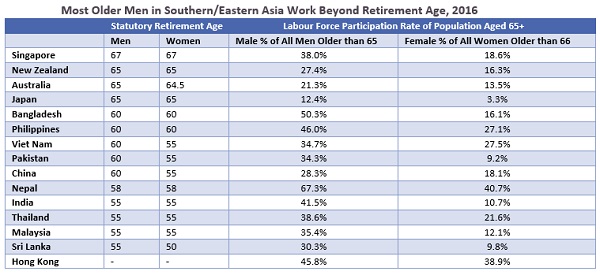

Hence, for most low-middle-income countries in the APAC, low pension coverage and low benefit levels have meant that many elderly people need to work longer despite a lower retirement age than in other regions such as Europe. This has encouraged work in the informal sector, which involves jobs that are dangerous, insecure, or poorly paid, with no social protection. This means the actual number of employees who continue to work beyond the age of 65 could be higher than illustrated below, and this is highly unlikely to change significantly for the next several years. |

|

|

|

Source: ESCAP, “Population Data Sheet —2016” |

|

Note: Table was sorted by Male % of All Men Older than 65 |

|

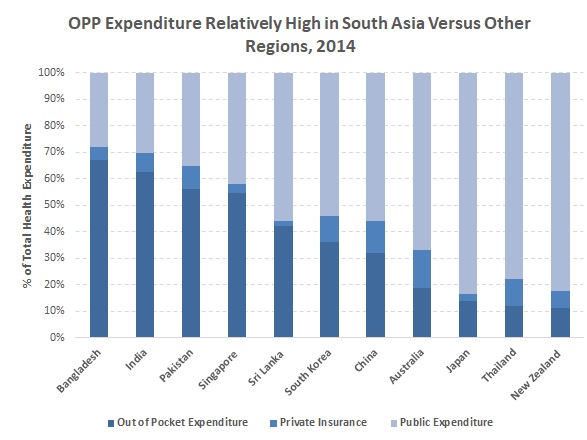

|

Healthcare in the APAC is still developing, with significant progress seen in Eastern Asia. However, as of 2014 (latest data available), in countries such as India and Sri Lanka, Out-of-Pocket (OOP) expenditure as a percentage of total healthcare expenditure was in the range of 40- 60%, as a result of lower public healthcare expenditure. Heavy OOP expenditure increases the financial burden on individuals, and this is a cause for concern in some regions such as South Asia, given the incidence of poverty and the need for well-structured healthcare services. This is also particularly a concern for the elderly who reside in these poor households and are unlikely to seek treatment for illness. Furthermore, healthcare coverage through personal insurance or corporate benefits is not readily available, especially in the case of elderly healthcare coverage. In instances where it is made available, it is often underutilised in many countries due to issues of affordability, trust in financial institutions, and Asian culture, where savings are seen as a valid means of provision. |

|

On a different note, some countries are showing improvement in public health financing. For instance, Thailand established a Universal Health Coverage (UHC) in 2002, following a public health financing reform. This has proven highly effective, as the country has been able to reduce OOP expenditure to 11.9% as of 2014 from 27.2% in 2002, significantly lower than in most other developing countries. Japan has also been successful in providing for public healthcare expenditure. Therefore, there is increased fiscal space for most other countries to expand their healthcare spend over the next few years. |

|

|

|

Source: World Bank, “Health Nutrition and Population Statistics” |

|

Note: Latest available data is for 2014 |

|

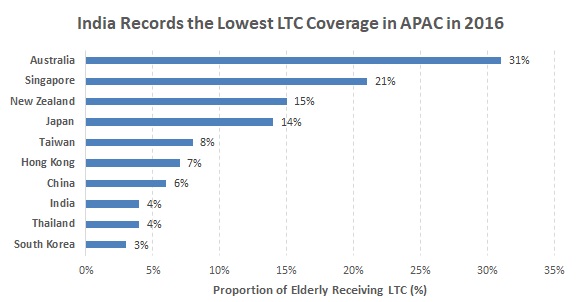

The next crucial aspect in healthcare for the elderly is access to long-term care (LTC). As the population of each country continues to age, more governments must consider new alternatives to provide and finance LTC. For most countries in the APAC, LTC involves unpaid care work by family members. This leaves many elderly people vulnerable to sickness and mortality risks. In the APAC, the level of utilisation is driven by availability and affordability of LTC services; however, cultural values also tend to play a part. Most Asian families take responsibility for their elderly and tend to avoid placing family members in care facilities. Therefore, LTC coverage for the elderly as of 2016 was the highest in Australia (31%) and the lowest in India (4%). However, most healthcare delivery systems that offer LTC services in the APAC have features in common that make them ill-prepared for non-communicable diseases. This has called for more investment in preventive healthcare in order to ensure healthier populations. |

|

|

|

Source: Marsh and McLennan Companies, “Advancing into the Golden Years: Cost of Healthcare for Asia Pacific’s Elderly” |

|

Will All of Southern Asia Prepare for the Looming Ageing Crisis? |

|

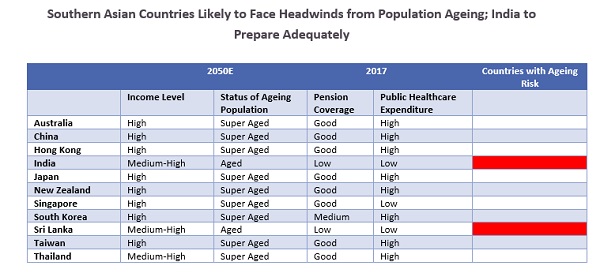

Population ageing is inevitable and is likely to affect sustainable development drastically, as poverty, economic, and health inequalities increase rapidly alongside population ageing. As discussed, old-age poverty is a concern, particularly for countries with inadequate pension schemes, where absolute poverty is significantly high. Similarly, old-age health care and LTC is critical; yet investment in health is insufficient to meet rising demand. However, most economies are likely to face time constraints, as many countries in the APAC are expected to age rapidly. This then highlights the most important question — are government budget projections in these countries adequate to handle the ageing crisis? |

|

|

|

|

|

Source: Compiled and classified by UZABASE based on UN World Population Prospects: 2017 Revision; CNBC, “Ageing Asia”; UN World Population Ageing Report 2015; PwC GDP Projects 2016-50 |

|

Note 1: Latest available data for pension and healthcare spending is for 2010 |

|

Note 2: Pension coverage: Good (above 75% contributory pension schemes), Medium (50-75%) and Low (<50%) |

|

Note 3: Public Healthcare Expenditure: High (above 50%) and Low (<50%) |

|

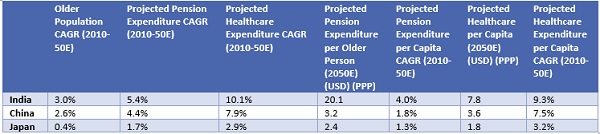

Based on our analysis, countries in Eastern/South-Eastern Asia/Oceania are likely to face less challenges from population ageing than South Asian peers by 2050. In the scenario above, China is projected to reach a high-income status and to also become super-aged by 2050E. Yet, as of now, China’s respective pension coverage and public healthcare expenditure are relatively better than India’s (India is projected to reach upper-middle-income status and ageing by 2050). However, as per CNBC (US-based internet and satellite business news channel), pension and healthcare expenditures in India on a per capita basis is projected to witness a strong growth trajectory, but still remain significantly lower than the spend in China and Japan. On a different note, countries such as Sri Lanka, Bangladesh and Nepal, where pension and healthcare coverage is poor, are likely to be inadequate to take on an ageing population. In addition, most Asian countries should take into account the constraints an ageing population places on discretionary spending given the higher financial burden, and create a possible strain on economic growth. |

|

However, our conclusion has the following limitations: |

| 1. Comparison of countries in a diverse income range and level of development: Japan moved into an ageing society a long time ago and has adapted well to the environment surrounding an aged population with good coverage of pensions and healthcare. |

| 2. Implications on purchasing power and economic growth have not been addressed, and which should be critical considerations for any country given the ageing crisis. |

| 3. The impact of population ageing and sustainable development is not limited to social security and healthcare. In fact, ageing also affects income inequality. Further research is also being carried out to identify links between ageing and climate change, environmental degradation, and sustainable consumption and production. |

| 4. Despite the fact that per capita pension and healthcare is growing, we have not analysed whether the level of spending is adequate to meet the growing needs of the aged society. |