Electric Vehicles in China: Racing into a New Energy Future

|

The Chinese government has been promoting electric vehicles (EVs) through steep subsidies and free licence plates in order to control worsening air pollution in the country. These incentives have not only helped drive EV demand, but have also supported China’s position as the world’s largest EV market (40% of all global EVs in 2016). Despite China’s leadership in the EV market, the share of EVs in total new vehicle sales in China remains quite low (only 1.4% of total vehicles in circulation). This has been mainly due to several concerns among consumers about EVs: their low average running distance, long charging times, and high prices. |

|

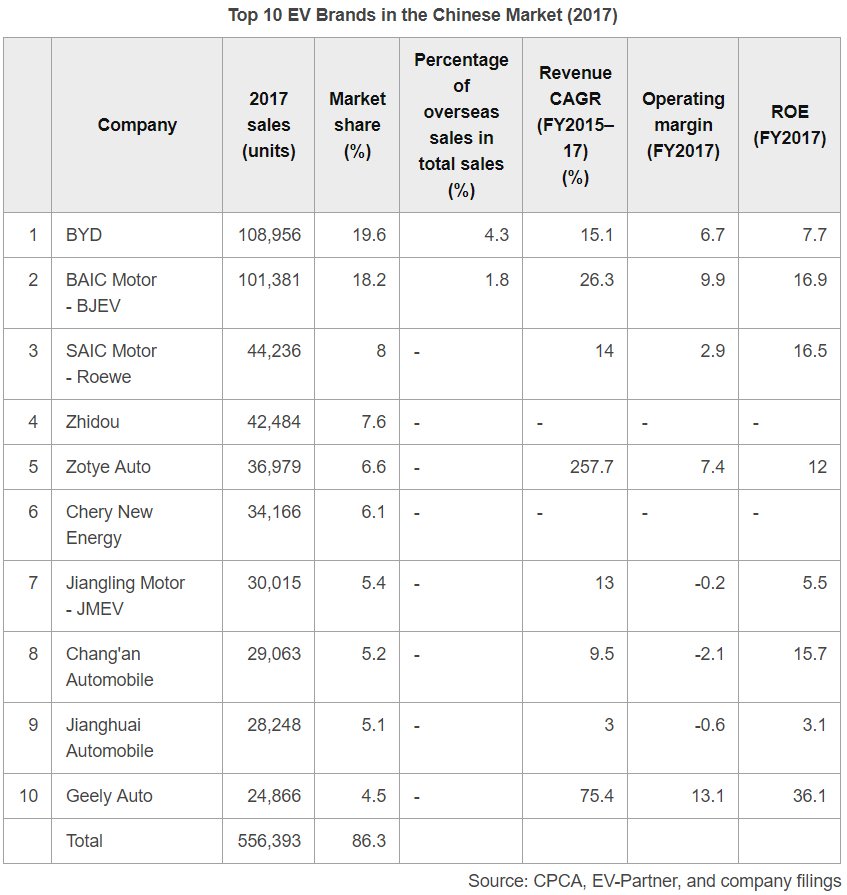

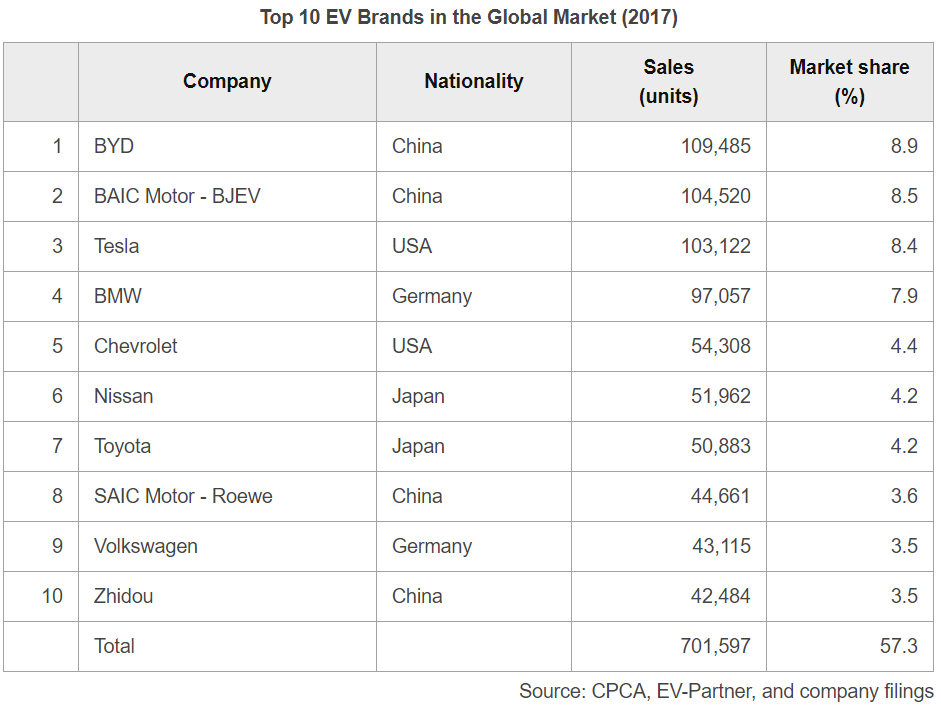

The Chinese market is considerably large, attracting both domestic and foreign EV manufacturers. Chinese automakers constitute most of China’s EV market, as they benefit from government subsidies. Although the subsidies have raised EV sales, they have also been detrimental. China has adjusted its policy in response: while it plans to phase out the subsidies, it introduced a dual-credit scheme to limit sales of petrol vehicles. As per the scheme, pure EV automakers will benefit from selling their surplus credits to traditional petrol vehicle manufactures. The scheme should force petrol vehicle manufactures either to adjust their production mix towards producing more EVs or to pay extra for purchasing credits from pure EV automakers. Furthermore, China is likely to follow other nations by setting a strict deadline on the implementation of a ban on petrol vehicle sales, and this should benefit EV manufacturers, especially both of China’s large automakers, BYD (19.6% market share in 2017) and Beijing Electric Vehicle (18.8%). |

|

In addition, given that China refines around 80% of cobalt sulphates and oxides (an important raw material in EV batteries), Chinese EV battery manufacturers such as Contemporary Amperex Technology should be able to acquire raw materials at lower prices and provide more economical batteries (which make up 48%–55% of an EV’s cost). We believe this to be a primary demand driver for the Chinese EV market in the future. |

|

Introduction: Battery EVs Dominate Global Market Due to Higher Capacity |

|

In general, EVs are grouped mainly into two types based on their electricity sources: battery EVs (BEVs) and plug-in hybrid EVs (PHEVs). The definition of ‘new energy vehicles’ (NEVs), a term used widely by the government and the media in China, encompasses both PHEVs and BEVs. BEVs are powered by battery packs that are re-chargeable only through external sources of electric power. PHEVs are powered by battery packs that are re-chargeable either through an external source or through an onboard generator. However, since the battery capacity of PHEVs is smaller than BEVs’, BEVs dominate the global EV market, accounting for about 60% of total EV stock. This Insight focuses mostly on the BEV industry, as BEVs are currently the mainstream in the EV market around the world. |

|

Note: This Insight uses two sources of EV sales figures: the International Energy Agency and the China Passenger Car Association (CPCA). Given that statistics from the CPCA focus only on the Chinese market, for comparison with other EV markets, this Insight uses data from the International Energy Agency. |

|

State Initiatives Support China’s Position as World’s Largest EV Market |

|

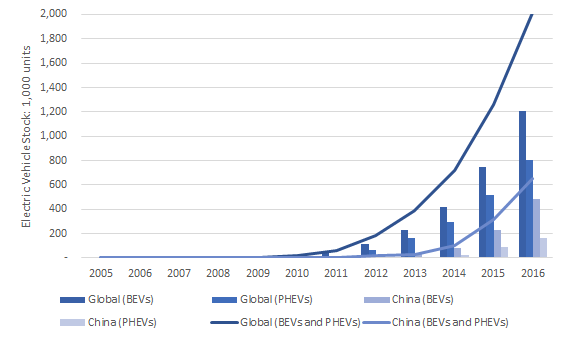

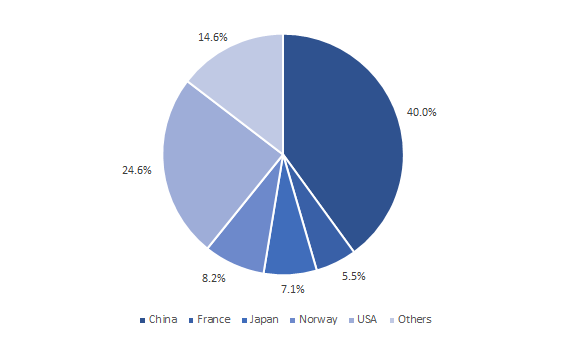

Faced with global warming and climate change, governments around the world have started to more strictly control carbon dioxide emissions, thereby driving EV sales. As per the International Energy Agency (an international autonomous agency that promotes energy security), the total global EV stock (BEVs and PHEVs) grew exponentially at a CAGR of 122.0% over 2010–16, reaching approximately 2 million units in 2016 (but just 1.1% of the total automotive market). While PHEV stock grew at a CAGR of 256.8%, faster than BEVs (104.7%), BEV stock accounted for 59.7% of global NEV stock growth. By region, China owned around 40% of global BEV stock, followed by the USA (24.6%) and Norway (8.2%). |

|

Rising Awareness of Global Warming Boosts Global EV Stock over 2010–16 |

|

|

|

Source: International Energy Agency |

|

China Leads Global EV Sales |

|

|

|

Source: International Energy Agency |

|

In response to increasingly severe air pollution, the Chinese government included green development and environmental protection as a major goal for the first time under its 13th Five-Year Plan (the latest) and aims to increase the usage of renewable energy and NEVs. The Chinese government’s most recent policies and plans show a commitment to renewable energy and NEVs, in response to a public outcry in major Chinese cities that faced worsening air pollution. The State Council’s “Planning for the Development of the Energy-Saving and New Energy Automobile Industry (2012–20)” (2012) stated the target for BEVs and PHEVs as 500,000 units in 2015 and 5 million units in 2020E (CAGR of 66.6% over 2016–20, from 648,770 units in 2016). Many cities have since implemented local subsidies, with PHEV subsidies estimated at CNY 65,000 per unit and EV subsidies at about CNY 110,000 per unit (around 40%–65% of purchasing prices), according to AutoForesight, an automotive research institute. |

|

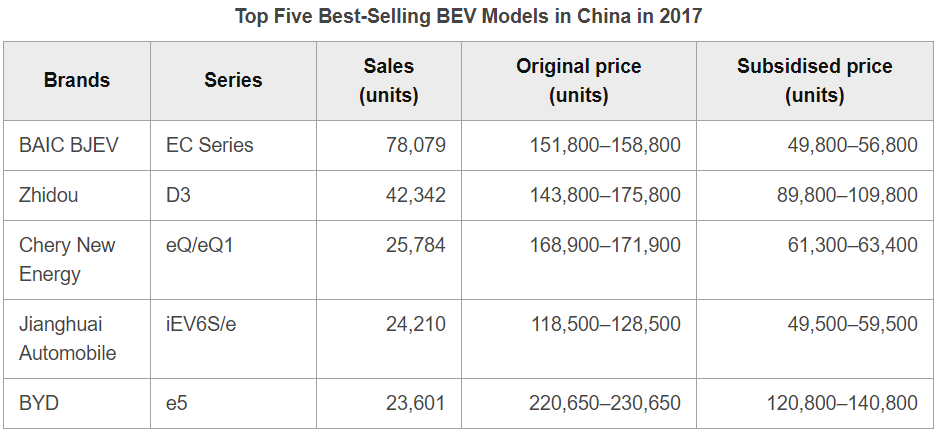

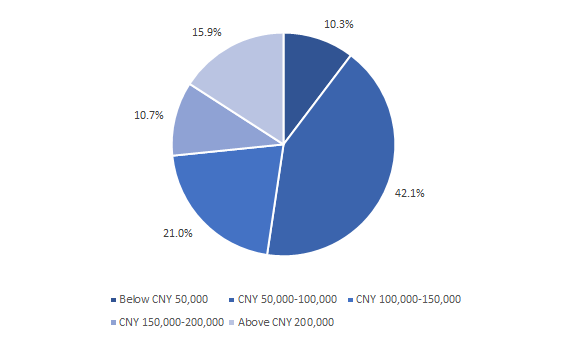

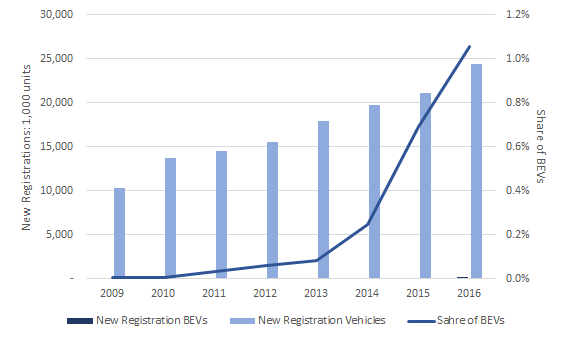

According to AutoForesight, the USA and Japan subsidise NEVs, and their ratio of subsidies is 10%–25% of EV purchasing prices. However, China’s subsidy ratio stands at 40%–65%. In China, EVs were commonly priced above CNY 150,000 for domestic brands and at over CNY 250,000 for foreign brands (e.g. Tesla, Nissan, and Chevrolet). Therefore, without the government subsidies, EVs in China are less attractive to consumers. With the subsidies, average prices of domestic EVs fell to CNY 50,000–140,000, which is within Chinese consumers’ preferred price range. Supported by the government’s incentives and subsidies, BEV sales expanded at a remarkable speed in China. Only 480 BEVs were sold in 2009, but sales rose to 257,000 BEVs in 2016, implying a CAGR of 145.4% over 2009–16. |

|

Moreover, in 2016, the Traffic Management Bureau under the Ministry of Public Security announced the introduction of green licence plates to identify NEVs (China’s standard plates are blue). Local authorities wishing to limit the number of vehicles in car-choked capital cities have a system of releasing new licence plates via a lottery just six times a year. The cost of a new licence plate may be even more expensive than a new car. In this environment, free green licence plates motivate individuals to opt for NEVs. |

|

|

|

Source: China Passenger Car Association; company filings |

|

EVs in Chinese Consumers’ Preferred Price Range of CNY 50,000–150,000 Form 63% of Total Car Sales in 2016 |

|

|

|

Source: Moto Trend |

|

Low Average Running Distance, Long Charging Time, and High EV Prices the Three Main Deterrents for Potential Buyers |

|

Although EVs have been a hot topic in the media and despite steep government subsidies for NEVs, the expansion of the market share of EVs has been notably slow. EV sales accounted for only 1.1% of total new vehicle sales in China (24.7 million units in 2016). |

|

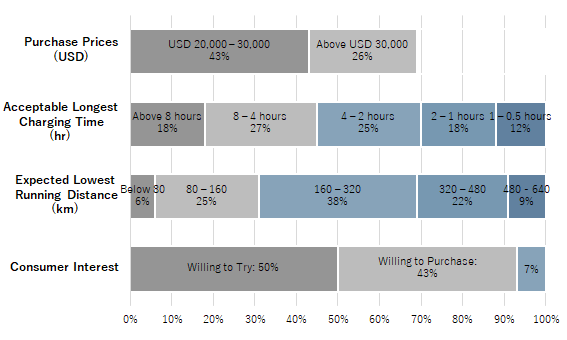

Based on Deloitte’s field survey, while customers showed an interest in purchasing EVs, the rate of conversion of potential customers to actual EV sales seems considerably low. The main reason potential buyers cite for their reluctance to purchase EVs is their low average running distance per charge, long charging time (a full charge might take around 30 minutes, as per the China Electric Vehicle Charging Infrastructure Promotion Alliance), and high prices (an unsubsidised EV costs over CNY 150,000, more than a petrol vehicle), to some extent. |

|

While running distance per charge has increased rapidly since 2016 (averaging only 100–150 kilometres [km] in 2016, but surpassing 200 km in 2017), customers expected a running distance of 330 km. In comparison, based on China’s fuel consumption standard (6.9L/100km), a midsized petrol vehicle with a 60-litre fuel tank can run 870 km. However, an EV with a 300 km running distance per charge still requires 2–3 charges. |

|

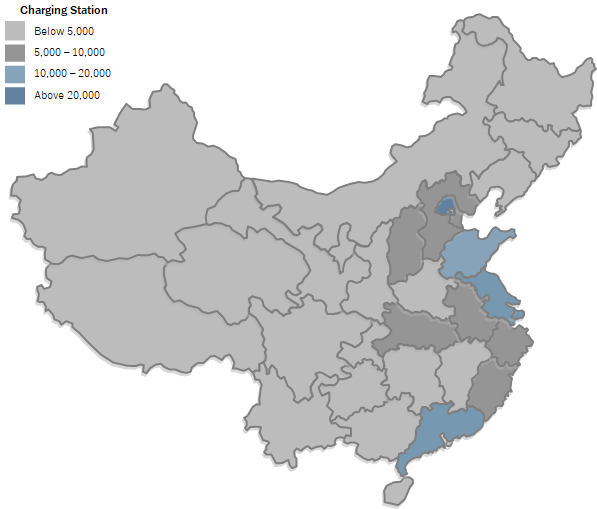

As of 2017, there were 213,903 charging piles in China, up 51.4% YoY from 141,254 in 2016. Most were located in the three main cities: Beijing, Guangdong, and Shanghai. The vehicle-pile ratio fell to 1 charging pile for 3.7 EVs (2016: 5.2 vehicles per pile) and is expected to fall further in 2018. However, the National Energy Administration reported the usage rate of charging piles as less than 15%. Many piles are located in remote districts around the city owing to lower land costs; therefore, they are not only inconvenient for consumers to reach, but also hard for operating companies to maintain. Piles in downtown areas often involve high parking fees due to limited space. Charging 3 hours for 10 kWh at China Power (CHN) costs CNY 19.86, for example, but parking costs CNY 30 (Shanghai’s average: CNY 10 per hour). Therefore, although the number of charging piles seems adequate, their utilisation rate remains low. |

|

EVs’ Share of Total New Registration Vehicles Small, Despite Rapid Growth in EV Sales in China over 2009–16 |

|

|

|

Source: International Energy Agency |

|

Customers Interested in EVs Have High Expectations |

|

|

|

Source: Created by UZABASE based on data from Deloitte |

|

Charging Piles Located Mainly in Big Cities |

|

|

|

Source: Created by UZABASE based on data from EVCIPA |

|

Removal of Subsidies for the Development of a Healthier Market and to Prevent Subsidy Manipulation Could Temporarily Threaten Growth Trajectory |

|

In general, consumer subsidies are temporary and unsustainable. According to the Ministry of Finance, the Chinese government spent over CNY 33.4 billion on funding NEV purchases over 2009–15, equivalent to 0.4% of the total government budget in 2015. As NEV sales expanded rapidly in China, relatively, the financial expenditure for subsidies grew in tandem. As estimated by the China Passenger Car Association (CPCA), around CNY 83 billion will be required to subsidise NEVs in 2016 and 2017 (0.8% of the total government budget in 2017). Furthermore, the current NEV market is mainly policy-oriented. With the rapid development of the NEV market, the government expects the market to shift from policy-oriented to become market-driven and provide a healthier competitive environment. |

|

In addition, the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) and the Ministry of Finance penalised five manufacturers involved in subsidy fraud in 2015. The subsidy scandal led to much criticism against China’s NEV subsidies policies. |

|

As a result, the government decided to start reducing the subsidies. In 2015, it published the “Notice on the Financial Support Policy for the Promotion and Application of New Energy Vehicles (2016-2020)”, giving a timeframe for the phasing out of subsidies by end-2020. The central government’s subsidy standard for NEVs will be gradually lowered 20% each year until 2019, with the subsidies expected to be completely eliminated by 2020E. The production and sale volumes of BEVs saw a significant drop after the first month of subsidy reduction in 2017. BEV production and sales fell to 5,857 units and 4,978 units respectively in January 2017, according to statistics published by the CPCA, at 63.8% YoY and 67.8% YoY respectively. |

|

The gradual elimination of subsidies will exert more operational pressure on NEV manufacturers. However, the phasing out of subsidies should force automakers to direct additional efforts into researching and developing NEV technologies to lower production cost. |

|

Launch of Dual-Credit Scheme Should Benefit NEV Manufacturers Through Trade of Surplus Credits; Traditional Automakers Will Be Forced to Adjust Production Mix |

|

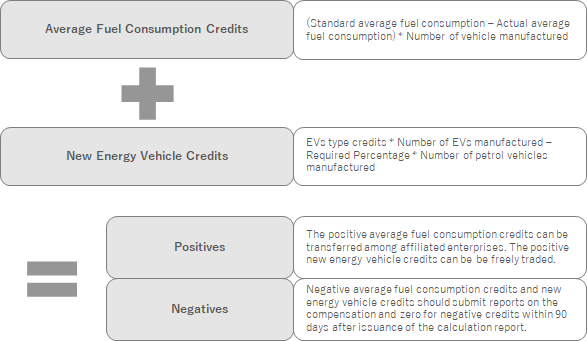

Before 2018, China’s policies related to NEVs focused mainly on encouragement, but currently they lean towards mandatory rules. In order to develop a sustainable NEV industry, the government decided to replace the fascial subsidies that it is phasing out with a dual-credit scheme: ‘Measures for the Parallel Administration of the Average Fuel Consumption and New Energy Vehicle Credits of Passenger Vehicle Enterprises’. The scheme was announced jointly by several related government departments in 2017. Effective since early 2018, it provides a system of credits comprising average-fuel-consumption credits and NEV credits. |

|

The average-fuel-consumption credits of a passenger vehicle enterprise are calculated by multiplying the gap between its standard average-fuel-consumption and actual consumption by the quantity of passenger vehicles manufactured/imported. If the actual value is lower than the standard value, positive credit is generated; if it is higher, negative credit is generated. Similarly, NEV credits are awarded to producers for whom the actual number of NEVs produced/imported are higher than the requirement stipulated by the authority. The standard requirement for producing/importing NEVs is calculated based on a certain percentage of petrol vehicles produced/imported by a particular enterprise. Average-fuel-consumption credits can be transferred among affiliated enterprises. NEV credits can also be freely traded among enterprises, although they cannot be carried forward to the subsequent year. |

|

The tradability of NEV credits compensates for the phasing out of NEV subsidies. The exact value and trading rules for NEV credit remain unclear, as the scheme was implemented in April 2018 and the first settlement day will be at the end of 2019 (results will be published in June 2020). As estimated by Chinese automotive magazine Automergers, total negative average-fuel-consumption credits will increase to around 26 million points in 2020E from around 1.7 million points in 2017 as fuel consumption standards grow stricter. The elimination of negative points demands substantial investment in fuel-saving technology. Such investments are expected to exceed CNY 130 billion by 2020E, growing at a CAGR of 302.1% from about CNY 2 billion in 2017 (3.3% of automotive industry revenue in FY2017). The cost of eliminating one negative average-fuel-consumption credit should hence rise to CNY 5,000 per credit from CNY 1,176 per credit over 2017–20E. The trading value of NEV credit should be lower than CNY 5,000 per credit in 2020E. |

|

The dual-credit scheme shows the government’s intention to eventually ban the sale of fossil fuel vehicles, and it should significantly impact both domestic and joint-venture foreign automakers. When the government reduced NEV subsidies, pure NEV manufacturers became concerned about potential losses, as NEVs have relatively lower demand but higher manufacturing costs than petrol vehicles. The dual-credit scheme should offer a new profitable approach for NEV manufacturers by enabling the trading of positive credits. Joint-venture foreign automakers that sell mainly fossil fuel vehicles in China should gradually adjust their vehicle mix towards NEVs or incur extra costs. |

|

Credit Calculation and Credit Usage in China’s Newly Launched Dual-Credit Scheme |

|

|

|

Source: Compiled by UZABASE based on various materials |

|

China Likely to Follow Suit in Banning Petrol Vehicles; Domestic EV Manufacturers to Benefit |

|

In 2016, Norway, where EVs’ share in the domestic automotive market is the largest (28.8% in 2017), announced a ban on the sale of all fossil fuel vehicles by 2025. The same year, Germany’s federal council passed a resolution for a ban on the internal combustion engine by 2030. France and the UK announced petrol and diesel vehicle bans starting 2040. Likewise, in India, the government is planning to end fossil fuel vehicle sales by 2030. Israel and Taiwan are also on the list. As of 2017, 15 countries and regions have decided to ban fossil fuel vehicles. However, for most bans, the time from now to implementation is over 10 years, and not all are legislated. Moreover, despite being termed “bans”, they generally restrict sales or new vehicle registrations, while allowing renewal of registrations for existing vehicles. |

|

China, although committed to greener development, is yet to announce an exact date for banning petrol vehicle sales. The Vice Minister of the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology revealed at the 2017 China Automotive Industry Exhibition that the government has been working on a time frame towards limiting and eventually eliminating fossil fuel vehicles; the closest deadline for the ban of sales might be 2025. Some automotive industry analysts from independent research institutes hold more conservative expectations for the deadline. Although policy is implemented faster in China than in other countries, EV market penetration remains low in China. Therefore, banning sales of petrol vehicles could take longer in China than in European countries (possibly 2035 or later). |

|

Host to the world’s largest new-vehicle market, China’s potential prohibition of fossil fuel vehicle sales should significantly impact not only petrol vehicle and EV manufacturers, but also related industries. Firstly, EV automakers will directly benefit from the ban. As mentioned above, EVs’ share of total new vehicle sales was only about 1.1% in 2016. Once the ban on petrol vehicle sales is issued, EV sales are certain to be boosted. Secondly, such a ban on petrol vehicle sales could improve China’s energy self-sufficiency. At present, two-thirds of China’s oil demand is met through imports; the ban should increase the energy self-sufficiency rate by more than 3% (79.4% in 2016), as estimated by the Electric Power Planning and Engineering Institute. Furthermore, NEVs, especially EVs, should provide basic infrastructure for the development of connected cars and self-driving vehicles. |

|

Several Countries and Regions Plan to Ban Petrol Vehicle Sales; China’s Restriction Likely the Soonest in 2035 |

|

|

|

Source: Compiled by UZABASE based on various materials |

|

Cheaper Batteries Should Allow China to Lower Production Cost, Given Its Control over Global Cobalt Supply |

|

One of the main differences between petrol vehicles and EVs is the rechargeable batteries of EVs. EV batteries differ from regular automotive batteries in that the former can provide power over a sustained period of time and are characterised by relatively high power-to-weight ratios, energy-to-weight ratios, and energy densities. Battery technology influences automotive performance and selling price. Bloomberg New Energy Finance estimates that the battery contributes about 48%–55% of the price of mass-manufactured EVs in the USA as of 2016. Depending on the speed at which battery technology develops, BEVs should remain more expensive than conventional vehicles for the next 7–10 years. |

|

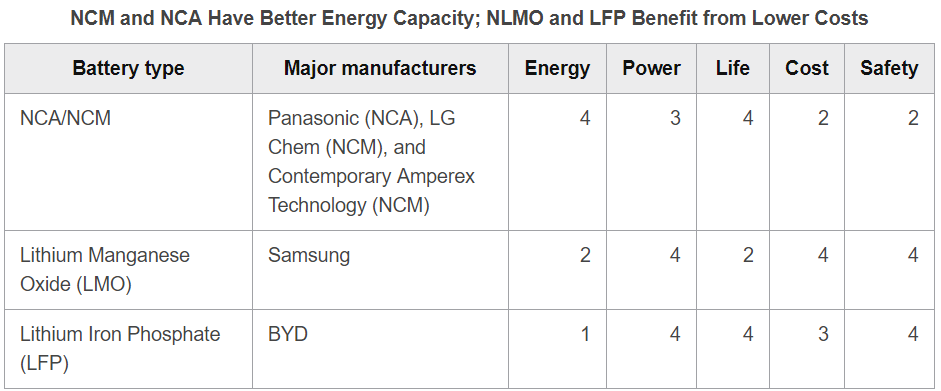

Most EV batteries are lithium-based and rely on a mix of cobalt, manganese, nickel, graphite, and other primary components. Some of these materials are harder to find than others such as cobalt. For both Lithium, Nickel, Cobalt, and Manganese (NCM) batteries and Lithium, Nickel, Cobalt, and Aluminium (NCA) batteries, cobalt is an indispensable material, accounting for around 20% of the battery cost. The price of Cobalt in London has risen more than 270% since the start of 2016 to USD 90,500 per tonne as of May 2018. Based on the latest data from the US Geological Survey, in 2017, about 58% of the global supply of cobalt originated from the Democratic Republic of Congo (Congo). Congo’s annual cobalt production was ten times that of the second-largest producer, Russia. However, 80% of cobalt sulphates and oxides are refined in China. The balance 20% is processed mainly in Finland, but it comes from a mine in Congo owned by a Chinese firm. This means China controls the global supply of cobalt, as reported by The Economist. |

|

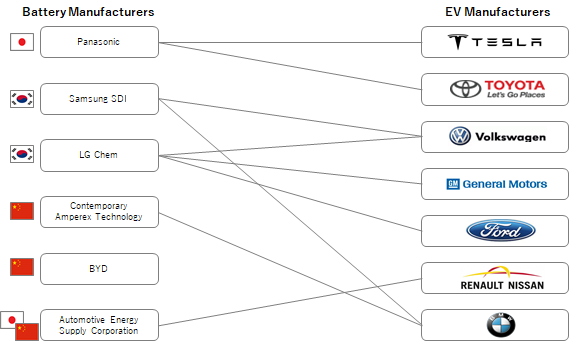

China’s control over the raw material of rechargeable batteries should further influence EV prices. For example, China Nonferrous Metal Mining Group (CHN) and Gécamines SA (COD) are cooperating to develop a cobalt copper mine in Congo. Glencore plc (CHE), the world’s largest cobalt producer, agreed to sell one-third of its cobalt production over 2018–20E to GEM Co (CHN), the main cobalt supplier of Chinese battery producer Contemporary Amperex Technology (CHN). Foreign battery manufacturers, especially the top three EV battery producers, incur additional costs to import cobalt from China, while Chinese producers obtain cobalt at lower prices. As battery prices account for a high percentage of the costs of EV manufacture, lower battery costs can lead to more affordable EVs, which in turn should help expand EV penetration. |

|

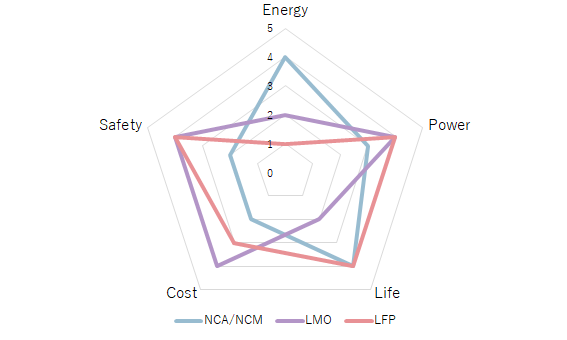

The lithium-ion battery market comprises five big manufacturers, based on revenue: Panasonic (JPN), LG Chem (KOR), Samsung SDI (KOR), BYD (CHN), and Contemporary Amperex Technology (CHN). Each company produces different types of batteries based on different combinations of materials. Moreover, although the top three companies are from Japan (12.4%) and South Korea (22.5%), six of the top ten companies were Chinese (accounting for 33.1% of the global EV battery market’s total revenue in 2016). |

|

|

|

|

|

Note: “Energy” stands for energy density, which determines the energy storage of devices. “Power” denotes power characteristics, which affect charging efficiency. “Life” stands for battery life. “Safety” indicates how stable electrode materials are, influencing the heat generated during charge/discharge. “Cost” denotes the level of cost of cathode materials |

|

Source: Advanced Energy Materials, “The Current Move of Lithium Ion Batteries Towards the Next Phase, 2012” |

|

Six Battery Companies Provide Batteries for Major EV Manufacturers |

|

|

|

Note: BYD batteries are used only in its own EVs |

|

Source: Newspicks |

|

Industry Dominated by Local Players Sees Increasing Competition from Foreign Players |

|

Although domestic EV manufacturers dominate the Chinese market, the performance and quality of their vehicles are not on a par with foreign brands. On the other hand, Chinese EV manufacturers who had thus far focused mainly on the domestic market are gradually venturing overseas. According to statistics from the CPCA, total NEV sales in China reached 556,393 units in 2017. Of this, all top 10 companies were Chinese enterprises (accounting for 86.3% of total EV sales in terms of volume). In addition, four Chinese enterprises featured among the top 10 global EV brands. In recent years, several large EV manufacturers such as BYD and BAIC Group began selling their EVs overseas. |

|

BYD, established in 1995, became well known when it launched its pure electric taxis in Shenzhen in 2004. The company currently owns several core technologies required in the full production of EVs, such as batteries, motors, electronic controls, and charging equipment. Since 2008, the company has released over eight different model series. It aims to develop self-driving EVs and openly announced that it will put the first self-driving vehicles into mass production by 2020E. |

|

Beijing Electric Vehicle was founded in 2009 by state-own automotive group Beijing Automotive Group. As of 2018, it had launched five major series and over 10 different EV models. The company positions its vehicles as ‘national vehicles’, i.e. vehicles that are known and accepted among people, through affordable prices. |

|

Despite the extremely low market share of foreign-branded EVs in the Chinese market, many international carmakers continue to actively carry out investments in China, as they are optimistic about future demand from the Chinese market. |

|

Tesla, the maker of the best-selling electric vehicles, announced in 2015 a manufacturing factory in Shanghai, as the company’s sales in China (accounting for about a fifth of total revenue in 2017) were all imports (subject to a 25% duty). Thus far, the Chinese government has required foreign electric automakers to join a local partner before building manufacturing facilities in China. Tesla’s project was therefore postponed over the years, as the company refused to enter the Chinese market via a joint venture. However, in April 2018, the Chinese government said that in the next five years it would ease the rules governing the entry of foreign electric automakers, and Tesla stands to benefit from this. |

|

BMW is currently adjusting the production proportions between fuel-engine and EVs in China in view of the new dual-credit scheme. In addition, BMW will enter a partnership with domestic manufacturer Great Wall Motor for EV production. |

|

The Japanese automotive brand Nissan launched a large-scale investment plan in China in 2017. In the five subsequent years, Nissan plans to invest about CNY 60 billion in R&D, production, and sales of EVs (around 9.5% of total vehicle revenue in FY2017). The company plans to launch more than 40 models in the Chinese market by 2020E, and EV sales should contribute 30% of company sales by 2022E. |

|

Toyota, which currently lacks pure BEV production, plans to release more than 10 pure EV models globally over 2020E–25E that will start to sell from China. |

|

|

|

|