Demonetisation: A Failed Attempt to Curb the Menace of India’s Black Economy?

|

A common issue that emerging economies across the world face is the wide prevalence of the black economy. While India has made significant progress in recent decades in terms of manufacturing, infrastructure, and technology, the country’s widespread black economy has been a major hindrance to its inclusive growth. |

|

This shadow economy has created inequalities in wealth distribution, with India’s richest 1.0% owning 53.0% of the country’s wealth in 2015 (up from 36.8% in 2000) and the richest 10.0% accounting for 76.3% of India’s wealth in 2015 (up from 65.9% in 2000), posing challenges to India’s dream of becoming an Asian superpower alongside its counterpart China. India’s black economy, unlike most other countries’, is a direct result of its heavy cash dependency, coupled with relatively lower levels of banking and financial inclusion. With the intent of eradicating the country’s black money roots, the Indian government implemented a measure popularly known as ‘demonetisation’ in December 2016, which involved the withdrawal of the legal tender status of high-denomination notes (INR 500 and INR 1,000) that constituted around 87% of total currency in circulation as of that date. The government anticipated that this measure would impact black money hoarders severely and root out black money from the country’s financial ecosystem in one sweep, as banks required that income sources be declared for the conversion of any old currencies amounting to more than INR 4,000 (a relatively low threshold of USD 62). However, the government’s expectations were not met, as per the latest reports released by the Reserve Bank of India. In addition, our analysis indicates that the costs of undertaking this measure outweighed its short-term gains by seven times. Hence, the question arises: Is demonetisation a failed attempt at eradicating India’s black money? |

|

Demonetisation has, however, offered India various long-term benefits. In recent years, the country has seen surging tax incomes (due to increased accountability), decreasing dependency on cash, coupled with growing usage of non-cash payment methods, and rising financial inclusion. Although the measure did not eliminate black money immediately, we believe these outcomes will reduce the country’s cash dependency, increase accountability, increase tax compliance and, in turn, stifle the black economy. That said, the government has a continuous role to play in the process of making the country less cash dependent and ultimately curbing black money. |

|

Black Economy – Culturally Accepted and Rampant Phenomenon Restraining Growth |

|

According to the World Bank’s latest available estimate (2007), India’s shadow economy comprising legal and illegal activities that are deliberately hidden from tax authorities was estimated to be 23.2% of the country’s GDP. Although this is much lower than that of countries such as Thailand (51.9%) and the Philippines (41.9%), it is twice that of China (12.8%). Many believe that this number is understated, given the general acceptance of tax evasion among Indians. Additionally, according to a report by Global Financial Integrity (GFI), in terms of black money outflows, India was ranked fourth, with an estimated average outflow of illicit finances per annum of USD 51.0 billion (4.6% of the global illicit finances) over 2004–14, surpassed by China (USD 139 billion), Russia (USD 104 billion), and Mexico (USD 52.8 billion). The sheer size of India’s black economy has been a major hindrance to its potential growth (one of the fastest-growing economies in the world [2016]) over the past decades. |

|

The black economy in most developed countries may refer to income earned from illegal transactions that are not disclosed to tax authorities. However, in India, it encompasses mostly income earned from legal transactions but deliberately not disclosed to tax authorities. The following are a few scenarios (of different magnitudes) of how tax evasion can be done in India, in order to understand the general acceptance of black money among the people. |

|

|

|

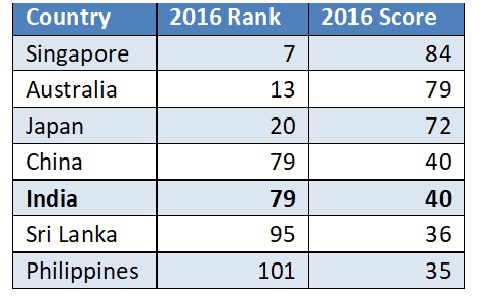

The black economy has resulted in several costs to India, such as the underestimation of GDP, a loss of revenue due to tax evasion, bribery and corruption, misinterpretation of the liquidity of money, and social inequalities, as the rich become richer and the poor become poorer. In addition, owing to this, in 2016, India was ranked 79th (out of 176 countries) by Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index, higher than most other Asian counterparts (a lower rank indicates low corruption). |

|

|

|

Source: Transparency International |

|

Note: Higher score and lower rank indicate low corruption and vice versa |

|

Black money dealings in India have traditionally thrived on two main fundamentally interlinked factors. As this report aims to understand the impact of demonetisation, these factors are now analysed here in a pre-execution context. |

| 1. Higher Dependency on Cash and the Dominance of the Informal Sector |

|

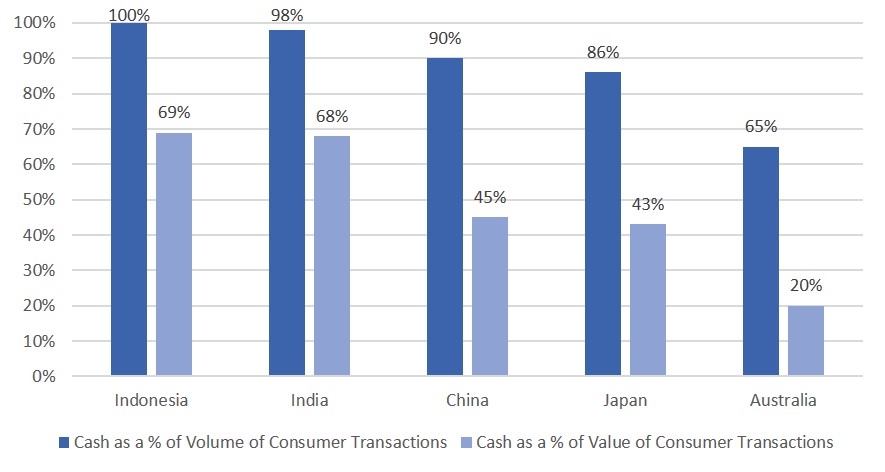

India has been largely a cash-driven economy. In addition to functioning as the most preferred medium of exchange in consumer transactions, cash also acts as a store of value for most Indians. Even Indians with access to formal banking often prefer to store and carry a lot of cash with them – mostly in high-denomination bills. According to a PWC report in 2015, around 68% of consumer transactions (in terms of value) in India are carried out using cash, higher than in countries such as China (45%) and Australia (20%). |

|

Further, in terms of the currency-in-circulation-to-GDP ratio, which can be used to measure the cash intensity of an economy, India was ranked one of the highest in the world. The country recorded a ratio of 12.5% in 2015, higher than that of other BRICS nations, namely China (9.3%), Russia (9.0%) and Brazil (3.4%), as well as other developed economies such as the USA, the UK and Australia (4-8%). |

|

India Accounts for Relatively Higher Cash Usage in Consumer Transactions |

|

|

|

Source: PwC, IAMAI and PCI – 2015 |

|

India Records Highest Currency-to-GDP Ratio among BRICS Countries, 2015 |

|

|

|

Source: The Curse of Cash by Princeton University Press based on data from Central Bank sources and National Statistical Bulletin |

|

Note: In order to show the impact of demonetisation, 2015 figures were used here. |

|

This high dependency on cash is further supported by the dominance of the informal sector in the country to facilitate black money transactions. According to the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), the informal economy, consisting of transactions and businesses not registered and hence difficult to be taxed, constitute nearly 82% of India’s total employment and 45% of gross value added (GVA) in 2016. This informal sector often engages in tax evasion activities, as cash is mainly used for transactions, and hence an audit trail (for tax authorities) is not left behind. |

| 2. Reluctance to Use Formal Banking Systems and Lack of Banking Facilities Restrict Tracking of Sources of Income |

|

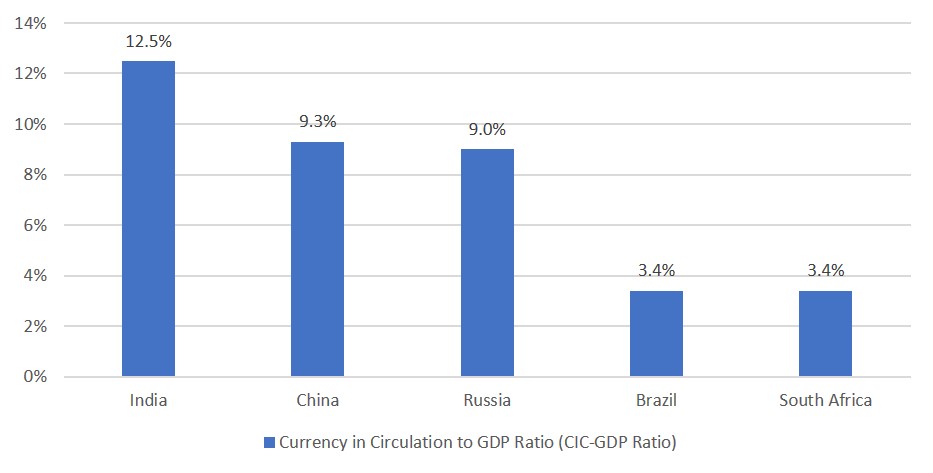

The higher dependency on cash and the wide prevalence of black money transactions has resulted in a significant share of unrecorded money (money that does not normally reach formal financial institutions) in India. Based on World Bank data, despite the country having moderately better banking infrastructure than peers (India recorded 12.9 bank branches per 100,000 adults in 2014, higher than China’s 8.0 and Malaysia’s 10.9), fewer people used the banking system. Around 47.2% of adults (aged over 15) did not have an account at a formal banking institution in India during the same period, considerably higher than in China (21.2%) and in Malaysia (19.3%). The main reason for a higher unbanked population is the general reluctance to use banking facilities. |

|

This significant share of the unbanked population, coupled with the dominance of the informal sector in India, indicates that nearly half of the working population did not have a bank account. Therefore, tax authorities could not track their income in any way. This has for decades been an unsolved mystery for the tax authorities. |

|

|

|

Source: World Bank Global Financial Development |

|

Note: Bubble size represents population as of 2014 |

|

Government’s Costly Measure Fails to Eradicate Black Money in the Short Term |

|

The Indian government has in the past implemented multiple initiatives to control the country’s black economy, for example via the Income Declaration Scheme of 2016 and the Benami Translation Bill of 2015. None of these measures have succeeded in limiting the black economy or in changing people’s behaviour and attitude towards black money transactions. However, many believed that demonetisation, implemented in November 2016, was an unprecedented and bold move by the Indian government. |

|

“Give me 50 days and I will give you the India you desired” – Prime Minister Narendra Modi |

|

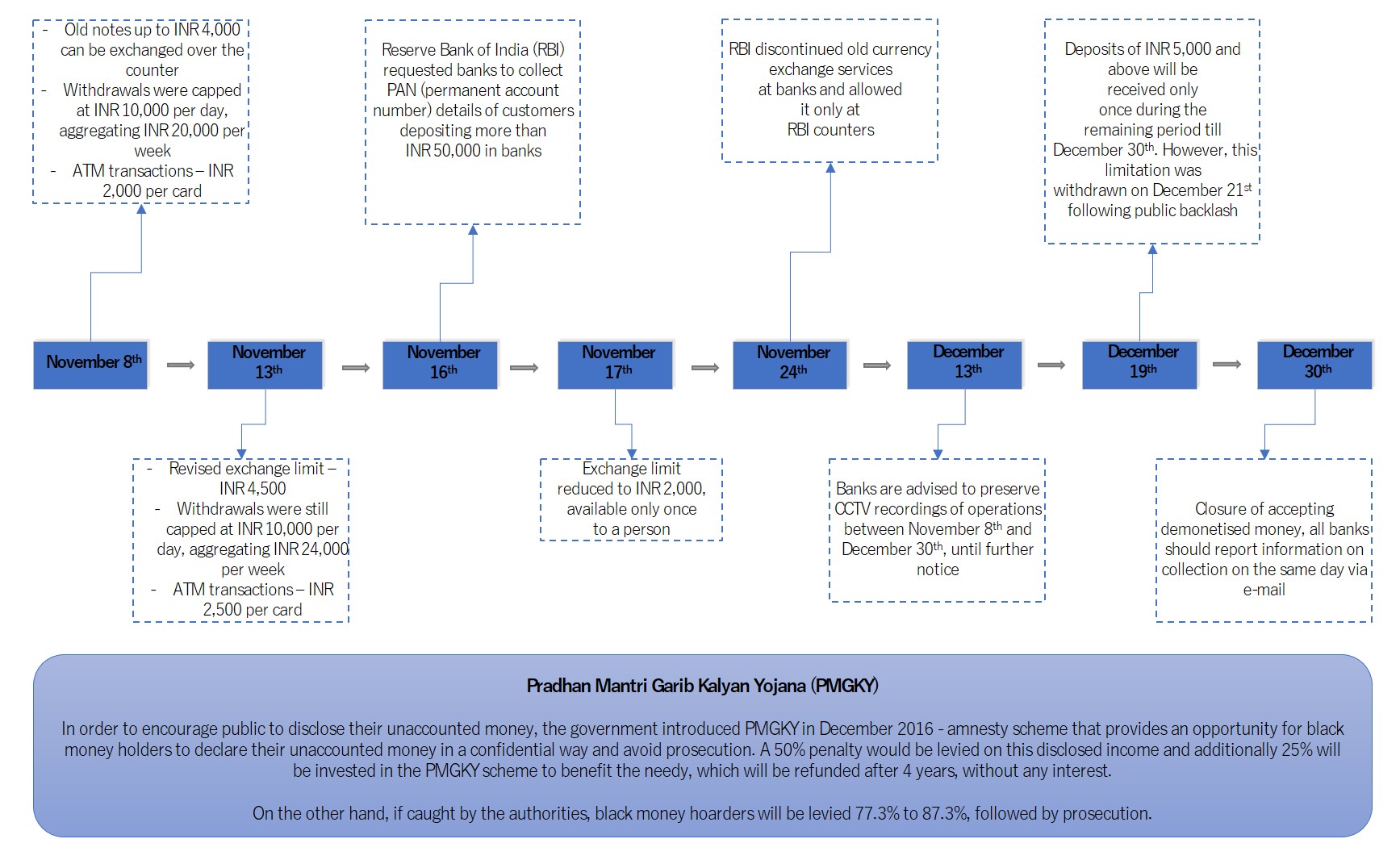

On 8 November 2016, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced via public broadcast that the country’s two high-denomination notes, INR 500 and INR 1,000, would no longer be legal tender – a course of action popularly known as demonetisation. He further requested the public to hand over or deposit old currencies at banks and post offices in exchange for newly printed notes (INR 2,000 and INR 500) before 30 December 2016, while restrictions were placed on deposits and withdrawals during this period. In addition, people were also required to disclose the source of their cash holding for exchanges exceeding a fairly low threshold of INR 4,000 (approximately USD 60). These demonetised high-denomination bills valued at INR 15,440 billion accounted for 86.9% of the total currency in circulation as of the demonetisation date . This initiative almost brought the entire country to a standstill for more than a week as thousands of people queued up outside banks and ATMs to exchange the cash in hand. |

|

The government stated that demonetisation was implemented as a measure to demolish the cash-centric shadow economy and eliminate counterfeit money in the country. By demonetising the country’s high-denomination notes and imposing restrictions on how money can be converted, the government aimed to make the conversion of black or unaccounted money difficult. From this move, the government anticipated that around INR 4,000-5,000 billion (26-33% of demonetised money) of currency in circulation held as unaccounted money would not be returned to the financial system, resulting in a windfall gain. |

|

|

|

Source: Compiled by UZABASE using data from various materials |

|

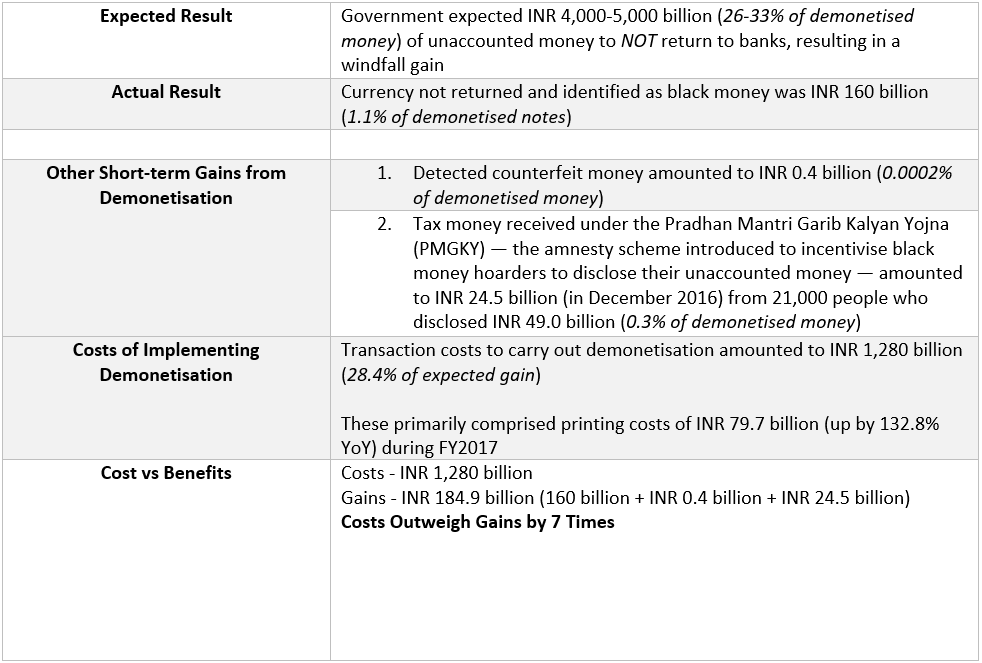

Nevertheless, the interim annual report released by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) in August 2017 indicated that as of June 2017 INR 15,280 billion (98.9% of demonetised currencies) had been returned to the RBI. This further proved that only INR 160 billion (1.1% of demonetised notes) had not been returned to the financial system, while the transaction costs of carrying out demonetisation were estimated at INR 1,280 billion. |

|

We can sum up the demonetisation move’s results (in the short term) as follows. |

|

|

|

Source: Compiled and calculated by UZABASE based on data from various sources |

|

As such, the demonetisation measure did not achieve the expected results in the short term (as previously anticipated), and only resulted in temporary economic instability (with GDP growth slowing to 5.4% in 4Q2017 from a high of 9.2% in 3Q2016 pre-demonetisation), a short-term cash crunch leading to public grievances, and a significant negative impact on the cash-centric informal economy, including unemployment. |

|

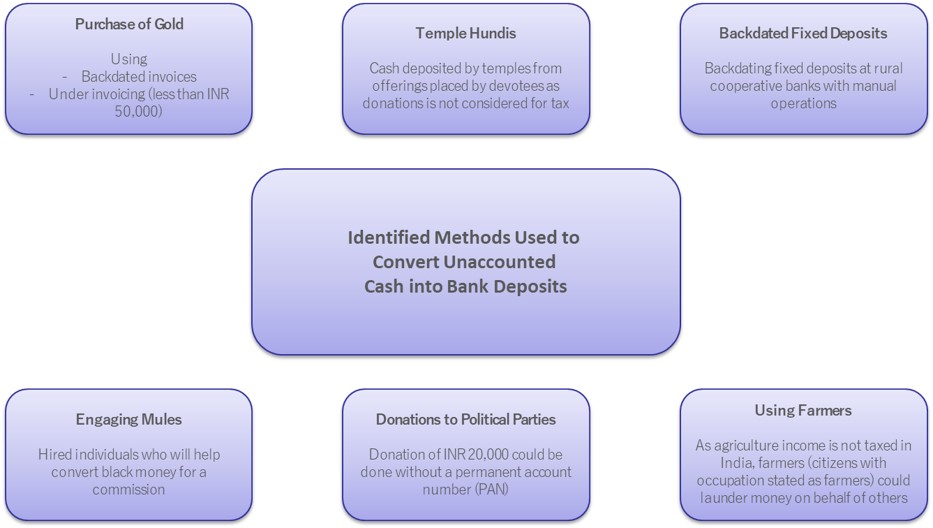

Although how India’s black money got its way back into the financial system cannot be clearly stated, various methods — such as using mules to convert currencies and backdating fixed deposits — could have been used by black money hoarders. |

|

|

|

Source: Recreated by UZABASE using data from KPMG – The Colour of Money: Black or White |

|

Looking at these numbers alone, demonetisation appears to have been a failure, heavily impacting India’s economy and the society’s wellbeing. The Modi government has been increasingly facing criticism for implementing the measure. Opposition parties claim that demonetisation was nothing but an act designed to convert black money into white. |

|

However, the country has been experiencing a few unanticipated benefits in the medium term, and we believe that these benefits, if sustained, are likely to make the demonetisation move a success in the long term and limit the black economy. |

|

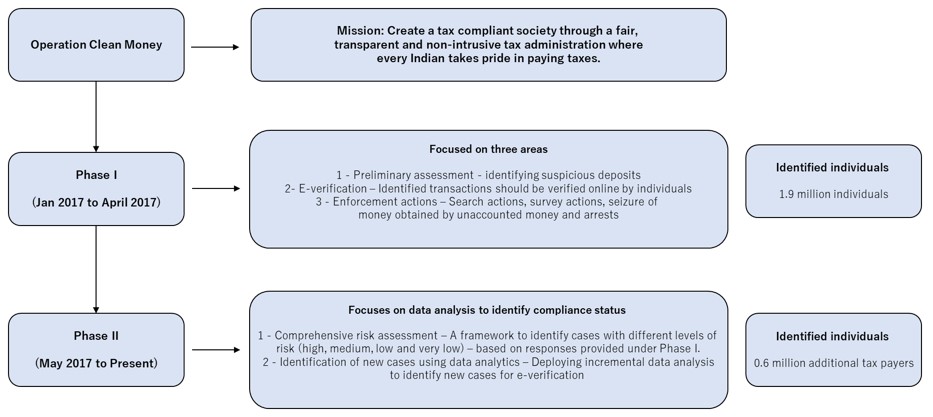

‘Operation Clean Money’ Likely to Continuously Stimulate Tax Income |

|

Following up on demonetisation, the Indian government, via its Income Tax Department, launched ‘Operation Clean Money’ in January 2017, wherein it requested electronic verification of large cash deposits made during the demonetisation period (9 November–30 December 2016). The government has been exploiting data analytics to identify suspicious deposits by comparing them with existing income tax databases. |

|

Owing to these measures, based on data available as of August 2017, 1.8 million individuals were identified for the verification process in Phase I (refer image below). Of this, around 50% were received by the income tax department providing information on INR 2.9 trillion (18.8% of demonetised money). Further, in Phase II, 0.6 million new cases were identified using advanced data analytics techniques. From November 2016 to May 2017, a sum of INR 175.3 billion has been identified as undisclosed income and INR 10.0 billion (5.7% of identified amount) has been seized by the income tax department. At the time of writing this report, investigations were still underway. |

|

Operation Clean Money – Framework |

|

|

|

Source: Compiled by UZABASE, using “Operation Clean Money Status Report” by the Income Tax Department |

|

These measures have benefited India by expanding the country’s tax base, in turn resulting in reduced black money. The number of tax returns filed stood at 28.3 million as of August 2017, indicating 25.3% YoY growth compared with 9.9% YoY growth recorded over the corresponding period the previous year. In addition, advance tax collections of personal income tax (other than corporate tax) grew 41.8% YoY as of August 2017, compared with 34.3% YoY recorded over the corresponding period the previous year. However, historical figures in this regard could not be tracked. |

|

Although it cannot be clearly stated whether this growth is a one-off occurrence or whether these measures will continuously drive government tax income, the income tax department claims that it now has a basis for identifying tax evaders. As investigations on suspicious deposits during the demonetisation period are still ongoing (and are estimated to take more than a year), we anticipate additional tax gains to the government in the near future. |

|

Reduction in Cash Dependency Driven by Rising Non-Cash and Digital Payments – A Leap Towards “Cashless India” |

| 1. Reduction in Cash Dependency |

|

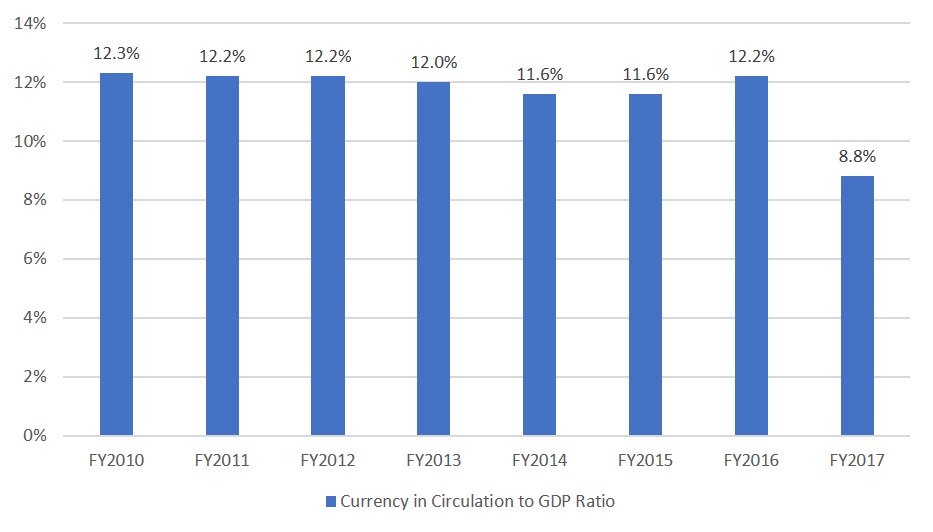

A notable change that could be observed in the country post demonetisation is its transition towards becoming less dependent on cash. As of FY2017, India’s currency-in-circulation-to-GDP ratio was recorded at 8.8% — the lowest during the past decade. While this rate compares favourably with developed and emerging economies such as Germany, France, Italy, and Malaysia, this indicator alone does not prove that the country’s black economy is under control. It only means that dependency on cash has decreased, which could possibly lead to a reduction in black money in the future. |

|

India Records the Lowest Currency-in-Circulation-to-GDP Ratio in Recent Years During FY2017 |

|

|

|

Source: The Wire |

| 2. Rising Non-Cash and Digital Payments |

|

Demonetisation has also forced people towards digital payments, driving the country towards a cashless economy. Many argue that the ultimate solution to India’s black economy and corruption is going cashless. Unlike cash payments, authorities can easily track digital transactions and they cannot be under-reported for tax evasion purposes. |

|

The Modi government recognised the importance of going cashless in 2014 and envisaged a “Cashless India” under its ‘Digital India’ initiative, with the objective of transforming the country into a digitally empowered society. Although transforming India into a cashless economy in the near future is a highly ambitious vision, demonetisation has helped increase the significance of cashless transactions to a large extent. The main reason for the lack of popularity of non-cash payment methods such as credit cards (including the ones who have access to such methods) among Indian consumers is their wariness of such methods. However, Demonetisation seems to have left Indians with no choice but to turn towards non-cash payment methods as an alternative to cash and to avoid the risk of holding cash. |

|

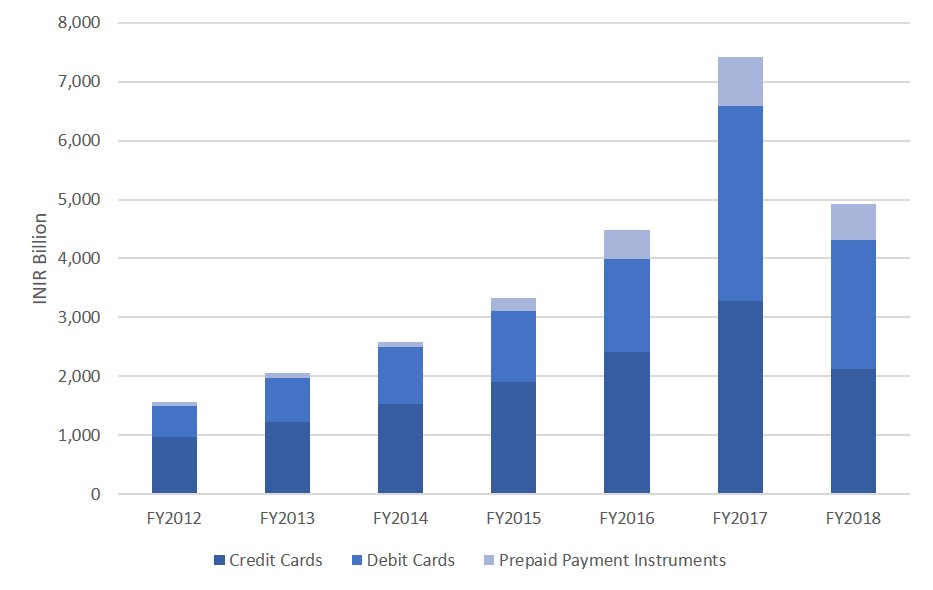

Consequently, in FY2017 (from April 2016 to March 2017), card payment transactions (transactions made via credit and debit cards directly at points of sale and via prepaid payment instruments such as m-wallets) grew by an impressive 65.5% YoY (compared with a 34.8% YoY the previous year) to INR 7,421 billion. In addition, as of September 2017 (first six months of FY2018), card transactions stood at INR 4,919 billion, 9.7% higher than the pre-demonetisation value of INR 4,484 billion recorded in the 12-month period of FY2016. |

|

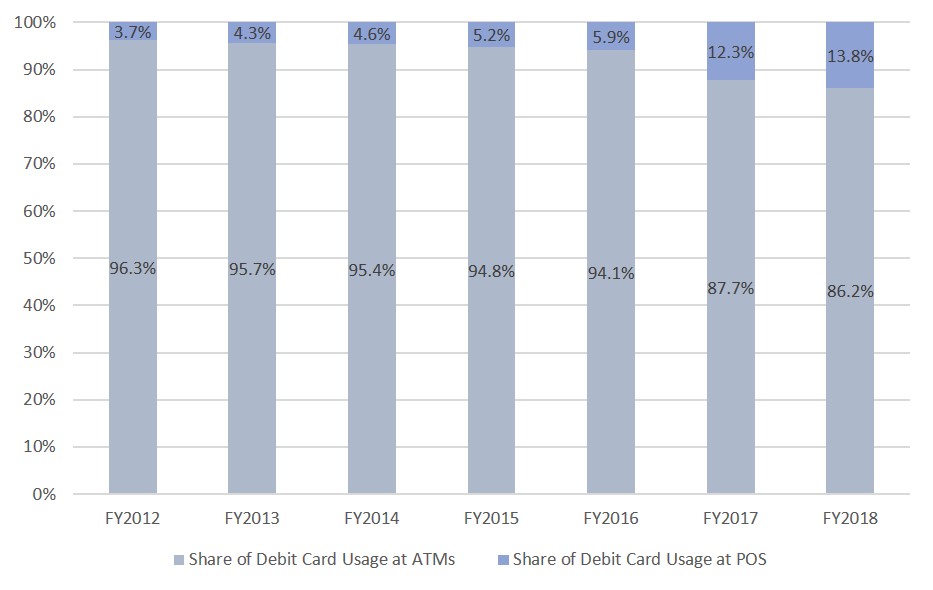

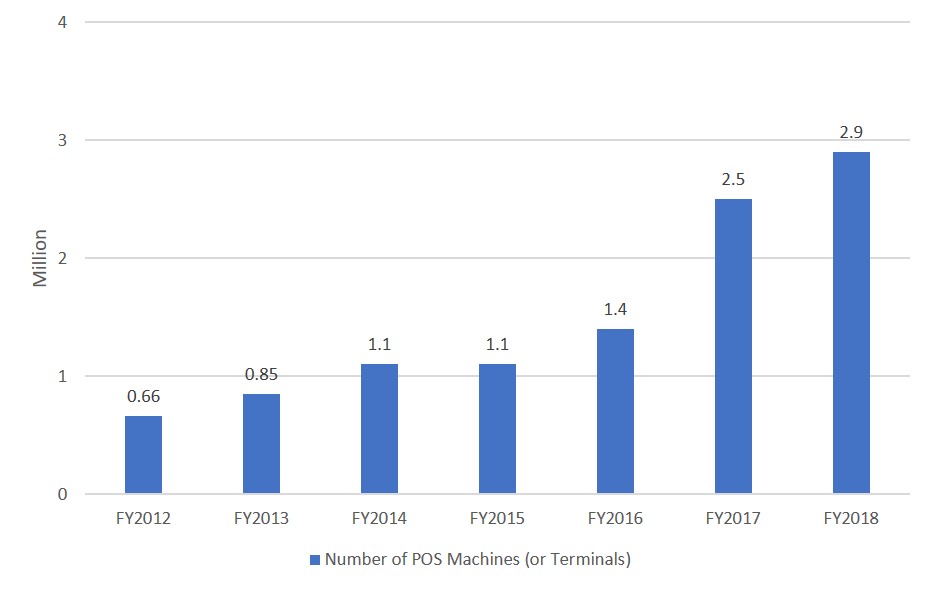

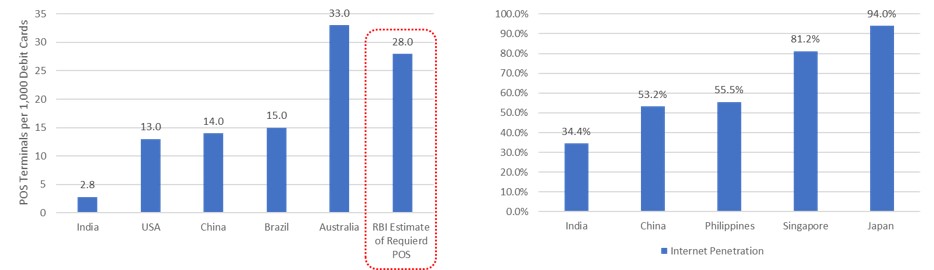

Despite this robust growth, a major challenge in achieving a ‘Cashless India’ is the paucity of network infrastructure such as point-of-sale (POS) terminals for debit and credit card payments. As of FY2016, India had only 2.8 POS terminals per 1,000 debit cards, significantly lower than in China (14), Brazil (15), and Australia (33). This is also reflected in the continued dominance of debit card usage at ATMs (86.2% in the first six months of FY2018) compared with that at POS terminals (13.8% in the first six months of FY2018), indicating a strong preference for cash, raising concerns in relation to a sustainable ‘Cashless India’. |

|

However, driven by this growing acceptance of digital payments, small-scale merchants including street vendors, tea stalls, and grocery stores in rural and smaller cities have been increasingly embracing non-cash payments by deploying POS terminals. Particularly, the number of POS terminals more than doubled to 2.9 million as of September 2017 from 1.4 million in March 2016. Consequently, we believe non-cash modes of payments could gain further traction in the near future and, in turn, pave the way towards an increasingly digital economy. |

|

Sharp Rise in Non-Cash Modes of Payments Post Demonetisation |

|

|

|

Source: Compiled by UZABASE using data from RBI |

|

Note: FY2018 includes period from April 2017 to September 2017 only |

|

Note 2: Figures include only POS payments by debit and credit cards |

|

Debit Cards Used Extensively for Cash Withdrawals Despite Impressive Growth in Debit Card Use at POS |

|

|

|

Source: Calculated by UZABASE using data from Reserve Bank of India |

|

Note: FY2018 includes the period from April to September 2017 only |

|

Number of POS Terminals More than Double over FY2016–18, Driven Mainly by Demonetisation |

|

|

|

Source: Reserve Bank of India |

|

Note: FY2018 includes the period from April to September 2017 only |

|

Note: Figures are as of March, except for FY2018, for which they are as of September |

|

Long Way to Go in India’s Journey Towards a Cashless Society |

|

|

|

Left Graph Source: YOURSTORY |

|

Right Graph Source: Internet Live Stats |

|

Note: Figures are as of 2016 |

|

Growing Awareness of Banking and Increasing Formalisation of Money and Financial Inclusion |

|

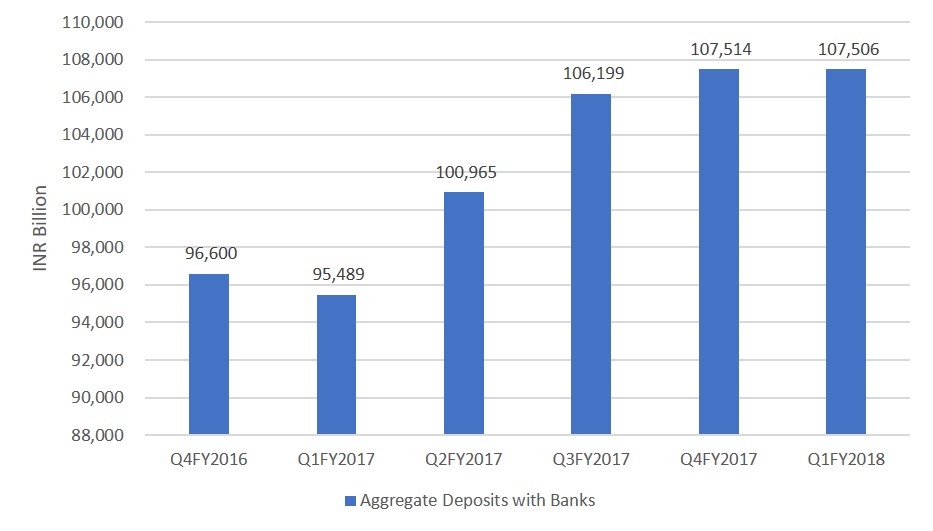

Demonetisation has brought about a behavioural change among people and made them realise the importance of using formal banking channels in turn resulting in an increased awareness of banking. Aggregate deposits with scheduled commercial banks in India grew 12.6% to INR 107,514 billion in 4QFY2017 from 1QFY2017, while it declined marginally by 1.1% QoQ to INR 95,489 billion in 4QFY2016 (prior to demonetisation). |

|

Steady Uptrend in Aggregate Bank Deposits Post Demonetisation |

|

|

|

Source: Reserve Bank of India |

|

Note: Demonetisation was carried out during 2QFY2017, hence we may assume that figures after 1QFY2017 to 3QFY2017 reflect its impact. |

|

Moreover, demonetisation has conveyed to the country’s rural population the importance of maintaining bank accounts, depositing money and using formal channels (such as banks) of money. Owing to this, awareness on financial inclusion schemes such as Pradhan Mantri Jan-Dhan Yojana (PMJDY) have been gaining popularity in the country, aiding the country’s significant unbanked population. This is likely to strengthen banking usage in rural areas and formalise its financial ecosystem. |

|

Demonetisation Likely to Be a Success Story in Near Future, Despite Short-Term Disappointment |

|

Although the demonetisation move may appear to be a failure on the face of it, considering the potential long-term payoffs, we believe that the measure could be considered a success. Most importantly, secondary outcomes of the move, such as the formalisation of the economy and the acceptance of digital transactions, are likely to prevent cash-based black money in the future. However, it has definitely failed to completely root out black money in one stroke or in the short-term, as originally intended. |

|

Demonetisation has mostly brought about a behavioural change in the Indian society and its perception towards cash. Arguably, it can also be perceived as a forced method to make people reach out to banking channels and embrace digital money. However, in a country like India where adopting new methods on a national level (especially among rural people) is viewed as unnecessary, a forced change is sometimes needed to bring about change to the society at large. We believe that any other measures or incentives to encourage digitisation, coordination among tax departments, and the transition of the informal economy into a formal one, would not have been successful at the same speed and urgency as demonetisation has been. |

|

We next consider how these by-products of demonetisation could support the elimination of black money inflows. We look at the previous examples of tax evasion methods in India and how these demonetisation outcomes (namely, growing formal banking and digital transactions) will prevent tax evasion, assuming the authorities are actively looking at suspicious transactions to identify tax evaders. |

|

Scenario 1 (land transaction): As this involves a significant amount, the money would have to come from a bank (as it would have been deposited during the demonetisation period). If the buyer wants to withdraw cash to pay for the property or make an online money transfer to the seller’s bank account, this will leave an audit trail for the income tax department to determine the actual selling price. Hence, the government will be able to earn the full tax income and avoid the creation of any black money. |

|

Scenario 2 (retail transaction): As the amount is not very significant, there is a chance this might go unnoticed. However, owing to the rise in digital payments, if the buyer decides to pay with a credit card, this will leave an audit trail and tax evasion could be prevented. |

|

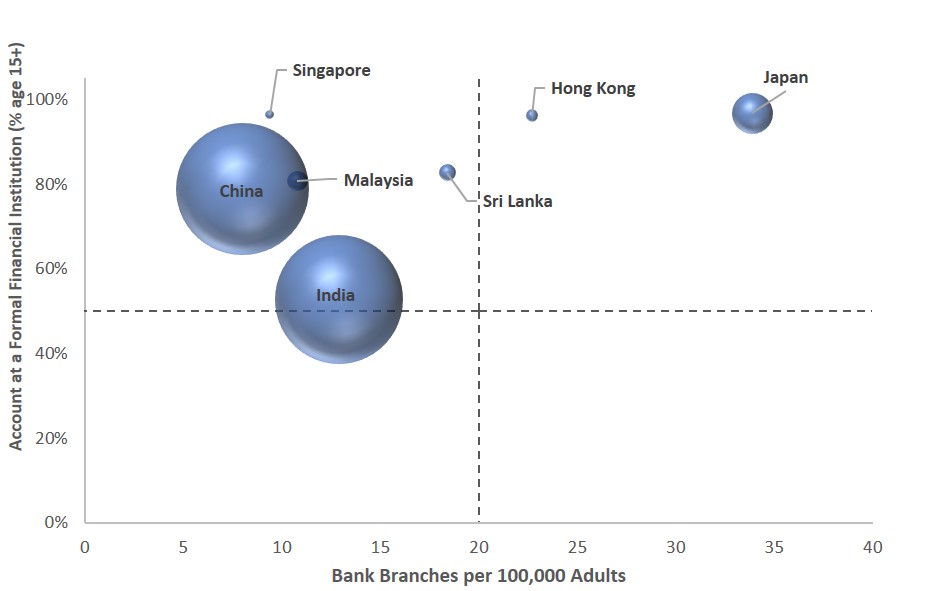

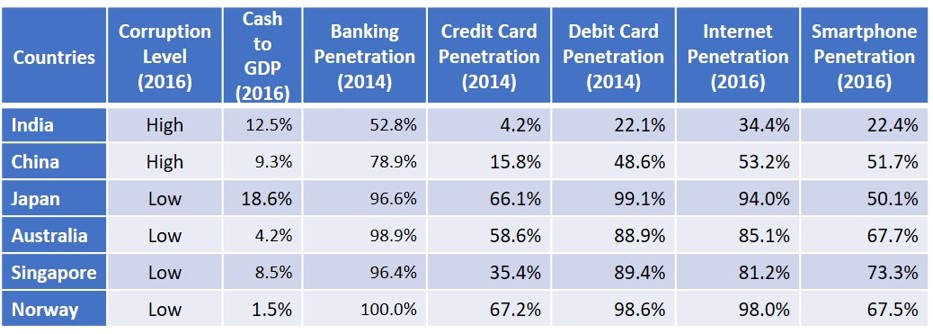

Despite these improvements, India has a long road ahead to become a less corrupt country (with a controlled level of black economy). A comparison with some of the well-known less corrupt countries indicates the pressure on the government to sustain these benefits and improve the political legal landscape. As such, demonetisation can be considered a stepping stone to create a fundamental structural change in the country in terms of people’s attitudes towards tax evasion and the black economy. In addition, we could also say that India is on its way, albeit gradually, to becoming a cashless economy and demonetisation has laid the foundation for it. |

|

India’s Dream to Become a Cashless Society Has a Long Road Ahead |

|

|

|

Source: Compiled by UZABASE based on data from World Bank, Newzoo, and various materials |

|

Note 1: Corruption level is based on Corruptions Perceptions Index; a score above 70 (of 100) is considered as less corrupt. |

|

Note 2: Due to unavailability of data for other countries, this comparison is based on figures before the execution of demonetisation, and hence the effects of the same are not reflected here. |

|

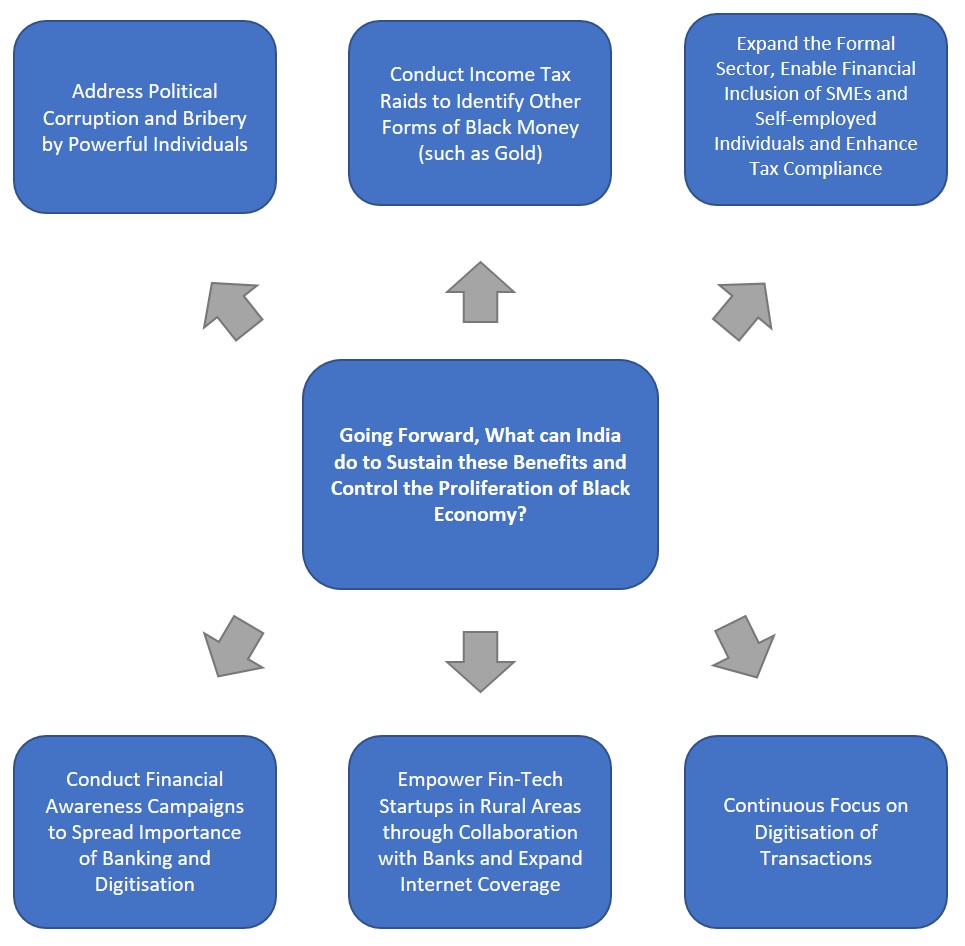

|

|

Source: Created by UZABASE |