China Supercharging Sri Lanka: Will ‘One Belt One Road’ Enter Energy?

|

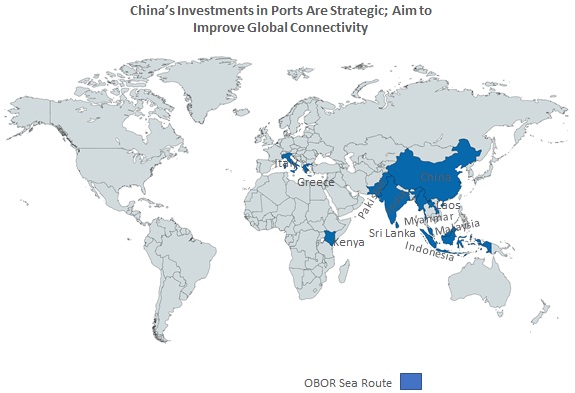

China’s One Belt One Road (OBOR) programme is a global infrastructure drive initiated in 2013 to enhance global connectivity through land and sea routes. The initiative had an initial budget of USD 5.0 trillion (of which only 18.0% was planned or underway at the beginning of 2017). Sri Lanka plays a key role in the OBOR sea route, along with Pakistan, Indonesia, Myanmar, Malaysia, and Kenya. |

|

These countries also share port and infrastructure quality metrics which indicate the need for investment in such sectors. Connectivity is the main goal behind the OBOR sea route; therefore, typically, ports have been targeted for the initial investment, followed by road and rail systems, special economic zones (SEZs), and energy projects. |

|

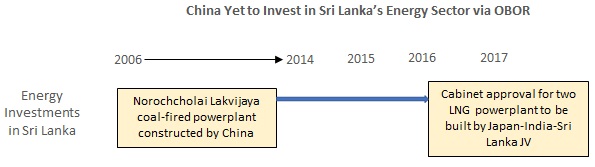

Although China’s first energy investment in Sri Lanka dates back to 2006 — for the coal-fired Norochcholai Lakvijaya power plant — it was not part of the OBOR initiative. Sri Lanka, much like the other countries included in the analysis, received investments in ports, followed by roadways, and a proposal for the establishment of a SEZ as part of the OBOR. However, China is yet to invest in energy in Sri Lanka through OBOR, despite its energy generation metrics being similar to those of regional neighbours that have received substantial investments. |

|

In 2017, China expressed a desire to establish a liquefied natural gas (LNG) power plant in Sri Lanka, and we believe this is likely to materialise, given the need for higher energy generation and openness to foreign investment in the sector. Sri Lanka’s relatively low per capita electricity production in 2014 (latest data available) supports this. Moreover, Sri Lanka has already approved the establishment of two 500 megawatt (MW) LNG power plants through a joint venture with India and Japan, and has also expressed willingness to establish more LNG power plants. While the investment value is difficult to estimate, it could range around USD 0.8-1.2 billion (around 36-54% of outstanding project loans from China in 2015), assuming a per MW cost similar to that in peer countries (USD 1.5-2.3 million) and similar power plant size. We believe the investment could expand Sri Lanka’s electricity generation by around 25% from its 2016 capacity. |

|

OBOR Sea Route Comprises Strategic Investments in Infrastructure and Energy Designed to Boost Global Connectivity |

|

OBOR is a global infrastructure programme initiated by Chinese President Xi Jinping, to increase connectivity between Asia, Europe, and Africa, with an end goal of boosting global trade flows and long-term economic growth. In 2013, China initially committed to invest USD 5.0 trillion in infrastructure (58.4% of China’s GDP in 2012 and 1.25 times the global infrastructure spend in 2012) through the programme. Fitch Ratings noted that projects worth USD 900.0 billion (around 18% of the budgeted amount) had been either planned or underway at the beginning of 2017. |

|

At its inception, OBOR piqued the interest of as many as 65 countries that were to receive infrastructure investments. These 65 countries represented 62.3% of the world population, 38.5% of global land area, 30.0% of global GDP, and 24.0% of global household consumption in 2013. A range of Chinese funding bodies also subscribed to the programme, ranging from the state-owned Silk Road Fund to China Development Bank, Export and Import (EXIM) Bank of China, and Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), among others. The initiative has broadened in scope since its inception, with member countries rising to 68 as of the most recent Belt and Road summit in May 2017, and with President Xi pledging additional funding of USD 113.0 billion to the programme. |

|

OBOR comprises a land route and a sea route. The sea route comprises primarily investments in ports in the target countries; through it China intends to enhance connectivity via increased number of ports, improved capacity at ports, and shorter shipping distances. Moreover, pivotal port investments follow a strategic pattern, targeting key ports across Asia, Europe, and Africa, along the OBOR sea route. |

|

Source: Quartz, “Your guide to understanding OBOR, China’s new Silk Road plan” |

|

Moreover, in addition to investment in ports, China has also invested in energy and infrastructure in many countries along the sea route in order to enhance the ports’ effectiveness. Hence, to predict the next investment in Sri Lanka, we considered investment sequences OBOR followed in peer countries. |

|

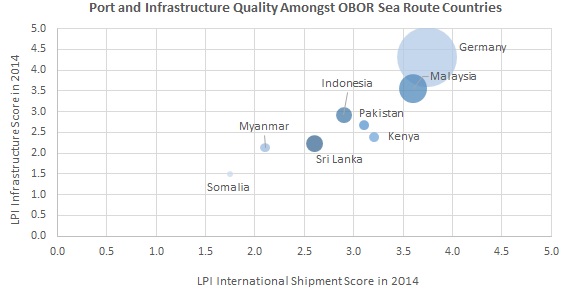

Countries considered for the analysis were those that are both part of the OBOR sea route whilst displaying development, infrastructure, energy, and port quality metrics, which suggest they will benefit substantially from investment in those sectors. |

|

Source: World Bank, “GDP per capita (current US$)”, “International LPI Global Ranking”, “International Scorecard” |

|

Note: Bubbles reflect the countries’ per capita GDP in 2014 |

|

Note2: Logistics Performance Index (LPI) was used as a proxy for infrastructure and port quality. Moreover, 2014 represents the latest available comparable data. |

|

Note3: Please note that Germany and Somalia represent the highest and lowest LPI scores, respectively, and have been included purely for comparison purposes. |

|

China Follows Specific Investment Sequence to Optimise Initial Investment in Ports |

|

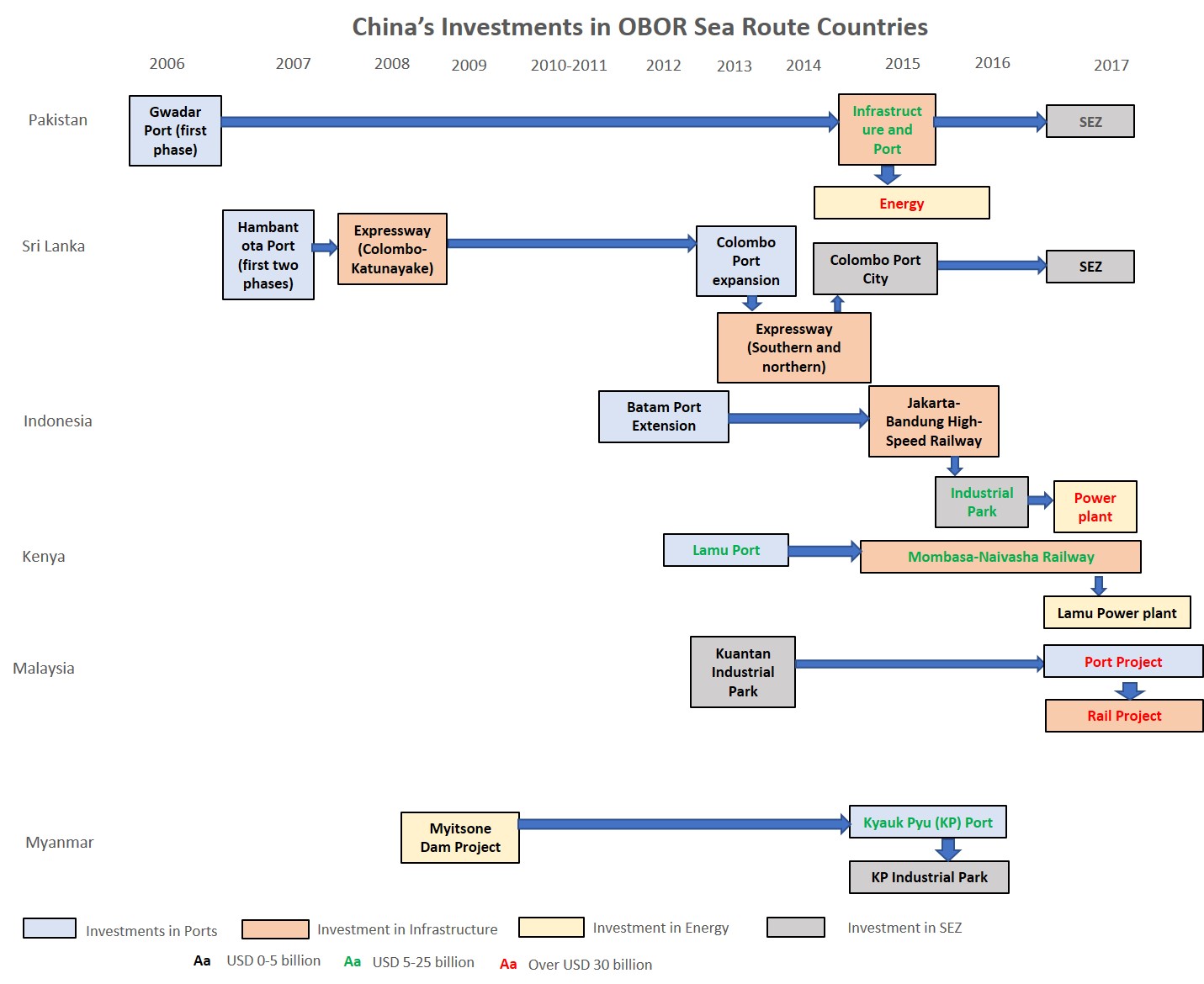

Given that connectivity is the primary goal behind OBOR, China follows a general sequence of investments to facilitate interconnections within and between countries. We note that among the OBOR sea route countries, China usually first invests in ports and then proceeds to invest in energy, infrastructure, and SEZs, as it sees fit. |

|

Source: Compiled by UZABASE based on various materials |

|

Note: Details of China’s investment in Pakistan’s SEZ was not available |

|

Note2: Investment value was not available for ports in Malaysia, although China’s overall investment in Malaysia’s port and railways is forecast to be USD 93.0 billion over 2017-37E |

|

|

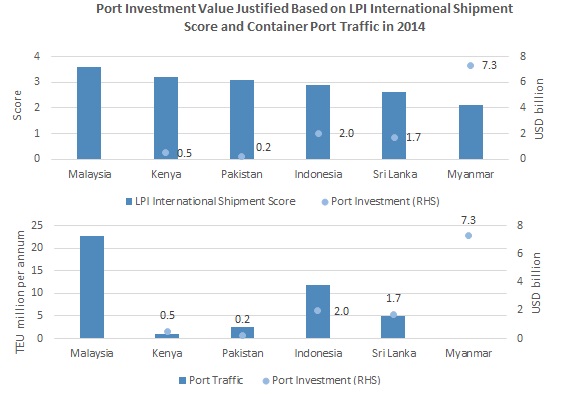

As mentioned, China has invested in ports of strategic interest to its government, primarily based on the ports’ geographic location. We note that its investment values tend to rely on the quality of port infrastructure and container port traffic in the respective countries. China has generally made higher investments in countries with lower-quality port infrastructure (as measured by the LPI international shipment index in 2014) and higher port traffic. |

|

|

|

Note: China’s investment in Kenya’s Lamu port comprises only the first three berths worth USD 0.5 billion (for which China won the contracts), while the overall project is worth USD 5.3 billion and will be completed by 2030E |

|

Note: Investment value was not available for ports in Malaysia, although China’s overall investment in Malaysia’s port and railways is forecast to be USD 93.0 billion over 2017-37E |

|

|

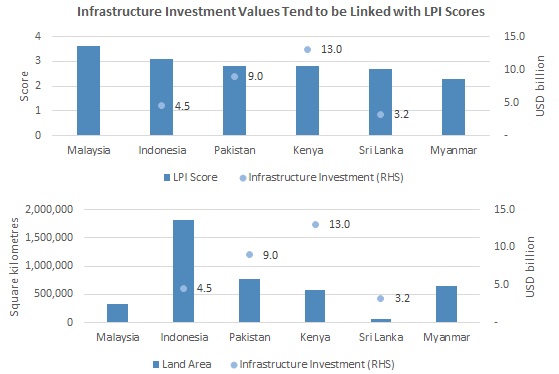

After investing in ports, China invests in infrastructure (to connect the port to the rest of the country effectively). China usually invests larger amounts in infrastructure in countries with lower-quality infrastructure. Countries with lower LPI scores have usually received higher Chinese investment in road and rail infrastructure. However, we believe the land size of the countries is also likely to play a key role in determining the road and rail investments required and their investment values. For instance, Pakistan and Indonesia received from China around three times and one and a half times the infrastructure investment Sri Lanka received, respectively, in spite of a slightly higher LPI score likely due to their greater land area. |

|

Source: Compiled by UZABASE based on various materials |

|

Note: Investment value was not available for ports in Malaysia, although China’s overall investment in Malaysia’s port and railways is forecast by CNBC to be USD 93.0 billion over 2017-37E |

|

Note2: Probable reason for China to not invest in Myanmar’s road and rail systems is explained below, under “Different Sequence of Investments in Myanmar Due to Dissimilar Motives of Energy Investment” |

|

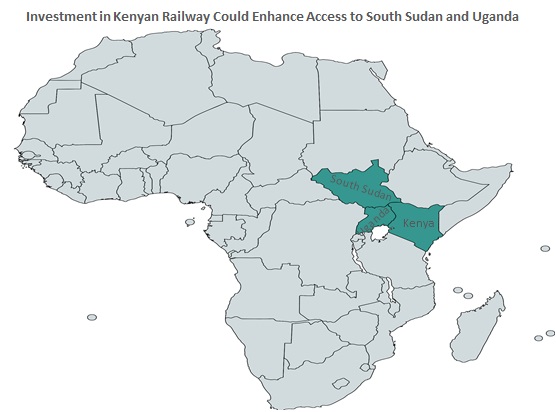

In addition to land area, we believe there are other factors that determined China’s high infrastructure investment in Kenya. Investment in Kenya’s railway allowed China to reach other landlocked countries, a benefit that the Gwadar or Hambantota ports do not offer. Once completed, the railway is set to be extended to Kampala in Uganda and Juba in South Sudan. Hence, we note that rail investment in Kenya provides broader benefits than simply reducing the lead time of cargo within Kenyan cities to Mombasa. |

|

Source: Created by UZABASE |

|

|

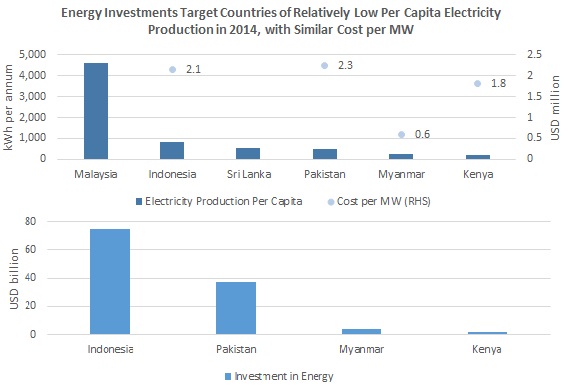

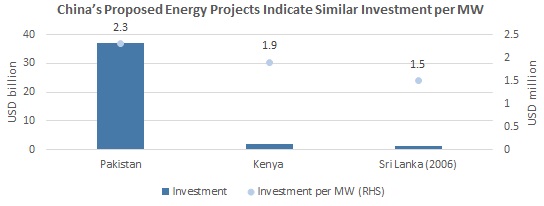

China has invested in the energy sectors of countries with relatively low electricity production; Malaysia has been an exception due to its relatively high energy generation capabilities. We further note that countries that received energy investments incurred a similar cost per megawatt (MW). However, Sri Lanka has so far not received an energy investment from China through OBOR, despite its energy generation metrics being similar to those of other countries in the analysis. |

|

Source: Compiled by UZABASE based on various materials |

|

Note: Note: Investment value per MW for Indonesia was derived based on the Indonesian president’s initial plan to raise energy investments over 2015-19E (which did not materialise) instead of China’s currently proposed energy investments. This is due to unavailability of data regarding China’s portion of currently proposed energy investment in Indonesia. |

|

Note: Myanmar’s significantly lower cost per MW probably results from its being the only hydropower project proposed |

|

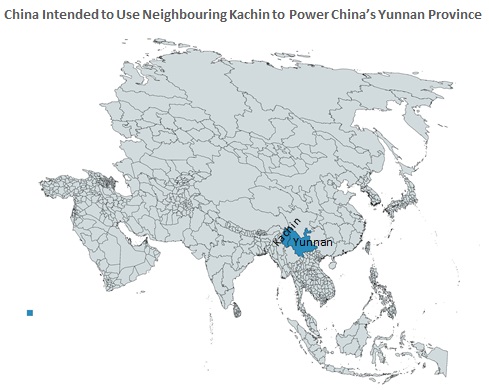

China’s investments in Myanmar’s energy sector was an exception to the general sequence, as its energy investment (Myitsone Dam in Kachin – consequently abandoned) took place before the investment in the port. The Myitsone project was not carried out with the intention of boosting domestic energy supply, but with an intention to power the Chinese province of Yunnan. Nevertheless, since the project was abruptly discontinued, China has indicated willingness to abandon the project in return for a substantial 70-85% stake in the Kyauk Pyu deep sea port. The Kyauk Pyu port is of special importance to China, as it provides an alternative, shorter route for oil and gas imports (through the port’s oil and gas pipeline) from the Middle East, bypassing the Malacca Straits. The focus of the port — to enhance oil transportation through a pipeline — limits the need for connectivity within Myanmar’s cities to its ports; this explains the absence of Chinese investment in Myanmar’s road and rail networks. |

|

Source: Created by UZABASE |

|

|

Among China’s investments in Malaysia, those that stand out are in steel and aluminium, through the Kuantan industrial park project. This investment was possibly driven by government regulations in Malaysia (absent in other nations) restricting Chinese steel exports to Malaysia. Additionally, this also hindered imports of Chinese steel by Chinese contractors carrying out operations in Malaysia, in turn justifying investments in plants within the nation to cater to their demand. The investment may have been further supported by Malaysia being a more prominent trading partner with China than other countries in the analysis. In 2016, China was the second largest export market for Malaysia (accounted for around 13% of Malaysia’s exports versus 2.1% of Sri Lanka’s exports and 7.8% of Pakistan’s exports) and imported 3.7% of its goods from Malaysia (Sri Lanka and Pakistan accounted for less than 0.2% of China’s imports, respectively). Moreover, given that Malaysia predominantly exported integrated circuits and semiconductor devices to China (accounting for around 57% of total exports from Malaysia to China, and about 11% of China’s total imports in 2016), which require steel and aluminium, the investment seems to be a strategic one towards improving import trade from Malaysia. |

|

China Likely to Invest in Energy Sector in Sri Lanka to Enhance Port and SEZ |

|

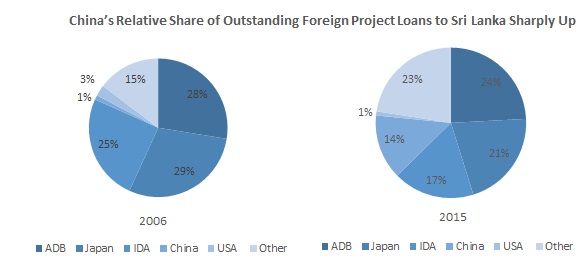

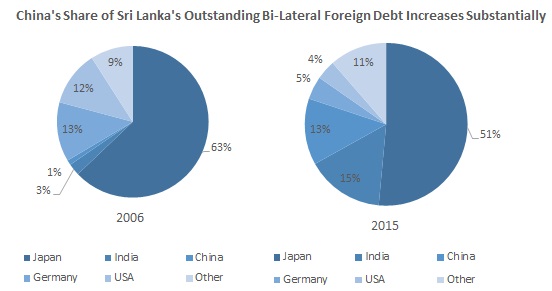

China has been maintaining close ties with Sri Lanka, as observed through a flurry of investments and lending to Sri Lanka, especially during in the recent past (2005 onwards). During the aforementioned period, China invested in a range of port, infrastructure, and SEZ projects, as highlighted in the sections above. In addition, China also invested in theatres, airports, and iconic towers in Sri Lanka (we believe these were more due to favourable relations between the countries, as opposed to OBOR connectivity gains for China). Growing investments from China have brought its share of foreign project loans to close to 14% by 2015 (latest data available; 1.0% in 2006) and its share of bilateral foreign debt to account for 13.2% in 2015 (2006: 1.1%). |

|

|

|

|

|

Close relations between the countries are likely to continue through OBOR, as China has pledged to invest a further USD 24.0 billion in the Sri Lanka (three times the current outstanding debt of USD 8.0 billion to China). Given that investments are likely to pour into Sri Lanka, the next question is which sector is likely to be targeted. Based on the sequence of investments followed in other OBOR sea route countries and on China’s already having established ports and SEZs in Sri Lanka, we believe the energy sector is likely to be targeted next to enhance the efficiency of the ports and SEZs. |

|

China’s only energy investment in Sri Lanka thus far was in the coal fired Norochcholai Lakvijaya power plant initiated in 2006 and completed by 2014 (USD 1.4 billion funded by EXIM Bank of China), which added 900MW to the national grid (around 23% of electricity generating capacity in 2016). This was prior to China’s investments in ports and SEZs, and was unlikely to have been established to enhance China’s investments in the country. We further note that Sri Lanka’s electricity generation in 2014 (post-Norochcholai), was still similar to that of Pakistan and Indonesia, both of which are expected to receive Chinese investment in energy due to the perceived lack of electricity production within the countries. The need for higher electricity generation, together with the Sri Lankan government’s approval of foreign investment in the energy sector, leads to a higher likelihood of energy investments from China to Sri Lanka through OBOR. |

|

|

|

|

In 2014, per capita energy production in Sri Lanka (549 kWh) was between that of Pakistan (510 kWh) and Indonesia (852 kWh). This suggests potential for energy investment in line with the general sequence of investments that China follows in OBOR. This is supported by higher industrial activity and investment in Sri Lanka, possibly leading to higher demand for energy production as well. |

|

Moreover, frequent power interruptions (as recent as October 2017) and continued inefficiencies of the existing Norochcholai plant further increases demand for energy investments in Sri Lanka. The government highlighted frequent breakdowns at the Norochcholai plant, rising fuel costs, and droughts — headwinds for energy generation. |

|

|

In July 2017, the cabinet of ministers of Sri Lanka approved two LNG power plants to be established through a joint venture with India and Japan, along with a floating LNG terminal and a gas distribution pipeline. These power plants are expected to have a capacity of 500 megawatt (MW) each and should increase the country’s energy capacity by around 25% from the 2016 capacity. |

|

China also expressed interest (in late-August 2017) to set up an LNG power plant in Hambantota, in line with the government’s policy to avoid establishing coal power plants. If the plans are implemented, Sri Lanka would effectively have its third LNG power plant. The plant is likely to materialise; however, the investment value is uncertain. Based on proposed investments in Pakistan and Kenya as well as past investments by China in energy in Sri Lanka, we estimate a similar investment value per MW. |

|

Moreover, the Sri Lankan Prime Minister noted that tenders were called for a fourth plant, highlighting the government’s intent to boost energy generation. Therefore, a power plant equivalent in size to those proposed by the JV (500 MW) could range around |

|

Source: Compiled by UZABASE based on various materials |

|

Note: Pakistan investment could reflect a mix of coal and LNG investments, while Kenya and Sri Lanka investment values relate to coal-fired power plants |

|

Note: Investment in Sri Lanka refers to the Norochcholai power plant |

|

|

We note that the proposed higher energy investments in Sri Lanka will complement China’s existing investments in the port and the SEZ. Hence, we believe that China is likely an indirect beneficiary from investments by foreign investors such as Japan and India in the energy sector. Therefore, even in the event that China is unable to establish its presence in Sri Lanka’s energy sector, the general investment sequence being followed in Sri Lanka could still benefit China. |