AgriTech: Can Digital Technology Lead Thai Rice Back to Profitability?

|

Since the failure of Thailand’s rice-pledging scheme in 2012, the country’s rice farming sector has yet to return to its glory days (the failure led to the prime minister at the time being sentenced to five years in prison for negligence). Prior to 2012, Thailand was the world’s number one exporter of rice for over three decades, before losing its crown to India. |

|

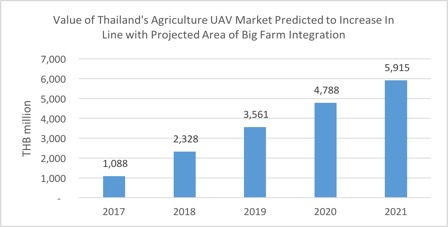

The country’s rice exports ranked second globally in 2016, accounting for 21.0% of the world’s total export value, behind India’s (26.7%). Apart from losing its market position, the profitability of Thai rice farmers also turned negative in 2013, when the farm-gate price of “major rice” (rice grown between 1st May and 31st October) was 5.8% lower than the cost of production per tonne, due to falling global market prices amidst oversupply. While it is difficult for rice farmers to predict their income to gauge profitability, as the price of rice as a commodity moves with global demand and supply, it is more practical for them to manage and control production cost to ensure profitability. One of the tools recently introduced in Thailand that promises cost reduction and yield enhancement is agricultural digital technology (AgriTech), e.g. unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV) with precision agriculture (PA) technology. Compared with countries such as Japan, which has been employing AgriTech for over two decades, Thailand’s AgriTech industry is considered to be in its infancy. AgriTech adoption in Thailand remains limited to large corporations (e.g. CPF Group and Mitr Phol Group), as AgriTech is still not cost-effective for small-scale farmers. However, the Thai government introduced the “Big Farm” project in 2016 to help farmers integrate neighbouring farmland and to thereby share production cost. Moreover, in an attempt to help farmers fund production, the Bank of Agriculture and Agricultural Co-operatives (BAAC) revealed a plan to increase the ratio of agricultural SME loans to 40.0% by 2020E from 3.0% in 2017. These initiatives should help make AgriTech adoption more affordable for small-scale farmers in the future. As such, Kasikorn Research Centre (KRC) predicts that Thailand’s agricultural UAV market could reach THB 5,915 million (USD 181.0 million) in 2021E, on par with the predicted future value of the Japanese crop-spraying drones market, suggesting bright prospects for Thailand’s AgriTech industry. According to our analysis, not only would the adoption of such technology return Thai rice farming to profitability, but it would also increase the chance for Thailand to win back its position as the world’s largest rice exporter. Nevertheless, KRC’s projection is highly dependent on the success of the Big Farm project; in 2016, agricultural land integrated under the project still accounted for less than 1% of total agricultural land in the country. |

|

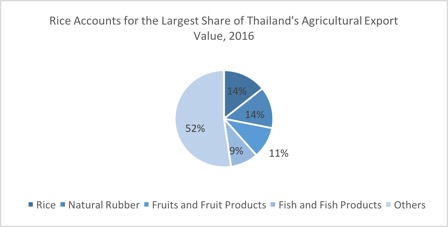

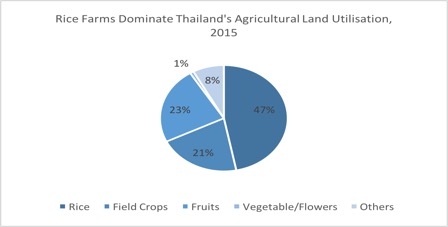

Rice – Thailand’s Most Important Agricultural Product Faces Declining Profitability The importance of rice for Thailand’s economy and for the Thai people is paramount. Apart from being the country’s staple food, rice is also Thailand’s number-one agricultural export, accounting for nearly 15% (THB 172.0 billion) of the country’s total export value of all agricultural products (THB 1,207 billion) in 2016 and contributing 1.2% of the country’s GDP. Around 30% of Thailand’s total rice production is exported annually. Moreover, nearly 50% of the country’s total agricultural land (149.2 million rai or 23.9 million hectares; 1 rai = 0.16 hectares) is dedicated to rice farming (2015), with rice farmers making up about 25% of Thailand’s total population (65.9 million) and about 70% of its agricultural population (23.9 million) as of 2016. |

Source: Office of Agricultural Economics |

Source: Office of Agricultural Economics |

|

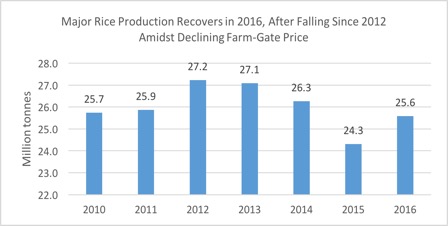

In Thailand, rice farming occurs in two periods, with major rice generally dominating production. In 2016, major rice made up 80.1% of total rice production in Thailand, while “second rice” (rice grown during 1st November and 30th April) formed the remaining share. In 2016, Thailand produced 25.6 million tonnes of major rice, a 5.3% YoY increase. Prior to that, during 2012–15, production declined at a CARC of 3.7% from 27.2 million tonnes in 2012. The fastest decline was observed in 2015, when production fell 7.6% YoY (partially attributed to drought that year). |

Source: Office of Agricultural Economics |

|

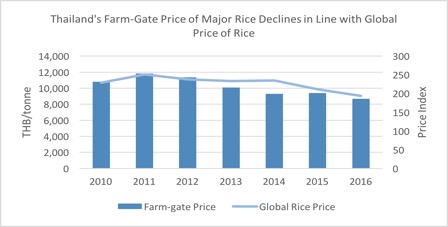

However, one of the main underlying causes of the consecutive decline in major rice production in Thailand during 2012–15 was a contraction in the farm-gate price of rice at a CARC of 6.1% to THB 9,403 per tonne in 2015. This decline has made rice production in Thailand unprofitable since 2013, when the farm-gate price of major rice was 5.8% lower than its cost of production per tonne. As such, in 2013, each tonne of major rice produced generated a net loss of THB 602. The situation worsened in 2014, when the net loss was THB 1,771 per tonne, before improving to a net loss of THB 399 per tonne in 2016. |

Source: Office of Agricultural Economics and Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations |

|

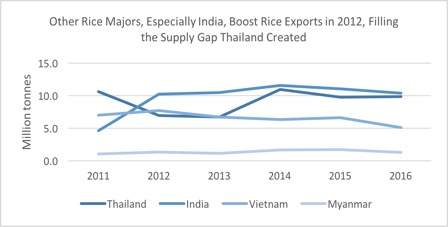

The declining farm-gate price of Thai rice could be attributed to the fast-declining global market price (the global price index of rice fell to 194 in 2016 from 251 in 2011). This was due to oversupply that resulted partly from Thailand’s previous rice policy. Under the rice-pledging scheme in 2012, the Thai government intended to purchase paddy rice from local farmers at a generous price (around 50% above the market rate) and to store it in order to create a shortage in the global supply, with the hope of spiking up global prices before releasing the rice back into the market at a premium. In this environment, rice farmers increased production of major rice by 5.0% YoY in 2012, hoping to benefit from the scheme. Unfortunately, the scheme triggered other rice majors in the region to boost exports, taking advantage of the intended export reduction by Thailand. For instance, in 2012, India lifted its export restrictions on non-basmati rice, leading export volume to more than double YoY (to 10.3 million tonnes); Myanmar increased rice exports by 26.2% YoY (to 1.4 million tonnes) and Vietnam by 10.2% YoY (to 7.7 million tonnes). This filled the supply gap in the global market, driving down the price of rice. |

Source: United States Department of Agriculture |

|

Study Shows Technology Could Slash Rice Farming Production Cost, Boost Yield, and Aid a Return to Profitability Around the world, both in developed and developing countries, farmers are starting to apply digital technology in farming, and Thailand is no exception. In 2017, Thailand was ranked 78th in terms of global ICT Development Index (IDI), ahead of most ASEAN peers except Singapore and Malaysia. More importantly, Thailand’s ranking is much higher than India’s (134th) and Vietnam’s (108th), its two main rivals in the rice export market. Therefore, with the agriculture sector contributing around 10% of the country’s GDP annually, several digital agriculture technology (AgriTech) companies have emerged in Thailand in recent years to seize opportunities offered by this unclaimed market. AgriTech players in Thailand currently include TechFarm (offers digital soil and water management systems), SkyVIV (agriculture drones), Happy Farm Kerdphol (agriculture drones), and FK Micro (fertiliser calculators). |

Source: International Telecommunications Union and United States Department of Agriculture |

|

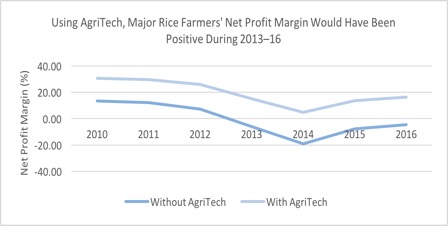

Since rice is arguably Thailand’s most important agriculture product, it is no surprise that it attracts a lot of attention from researchers and technology developers. One company that already has a presence in the country is Bayer, a German multinational life science company. In partnership with the German Agency for International Cooperation (GIZ), it started experimenting with unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV), specifically drone technology, for rice crop improvement in Ubon Ratchathani (where around 6% of Thailand’s total rice cultivation is located). The company revealed that aerial data collected through this technology enabled farmers to monitor rice paddies within minutes, instead of spending days on foot, and to obtain timely information on crop ripeness. This cuts labour cost and the cost of replanting spoiled crops, ultimately cutting production cost by 20% and raising yield by 20%. Assuming that rice farmers could reduce production cost by 20% using AgriTech, our analysis suggests that they would still make a profit for every tonne of major rice produced during 2013–16 despite a declining farm-gate price. Using AgriTech, rice farmers would have generated a net profit of THB 1,413 per tonne of major rice produced in 2016 (instead of a loss of THB 399 per tonne), equivalent to a net profit margin of 16.3% per tonne. |

Source: Office of Agricultural Economics and UZABASE Calculation |

|

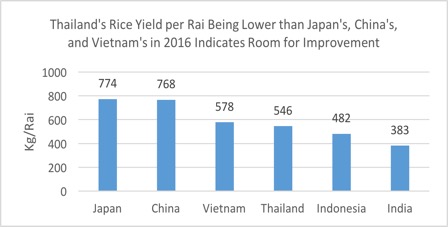

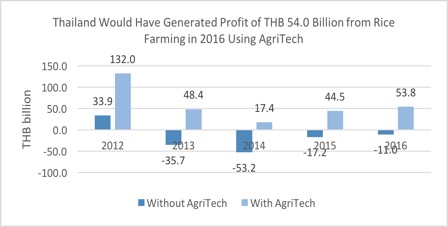

In 2016, Thailand’s average major rice and second rice yield per rai combined stood at 546 kilograms (kg), behind Japan’s (774 kg/rai), China’s (768 kg/rai), and Vietnam’s (578 kg/rai). If Thai farmers enhanced rice yield per rai by 20% through AgriTech, average yield would have increased to 655 kg/rai in 2016, 13.3% higher than Vietnam’s (although 18.2% lower than Japan’s and 17.3% lower than China’s). The higher average yield would have in turn led to a 24.8% increase in Thailand’s total rice production (major and second rice) to 38.3 million tonnes in 2016. When a healthy level of profitability is reached using AgriTech, Thai rice farmers will be motivated to continue producing rice. Assuming that the export level remained at around 30% of production volume annually, Thailand would have exported 11.5 million tonnes of rice in 2016, 15.0% more than India (10.0 million tonnes). Consequently, although the incremental rise in average yield would not have resulted in Thailand generating the highest yield in the region, it would have increased the chance for Thailand to regain its position as the world’s largest rice exporter. |

Source: Office of Agricultural Economics |

|

Furthermore, the increase in yield per rai and the 20% cut in production cost would have allowed THB 53.8 billion in net profit from rice production in 2016, instead of a loss of THB 11.0 billion. Apart from Bayer’s drone technology, Rangsit University conducted a test using a precision agriculture (PA) solution on Hom Pathum Rice in Kanchanaburi province, and this resulted in an even higher increase in yield: a 27% increase. |

Source: Office of Agricultural Economics and UZABASE Calculation |

|

Thailand’s AgriTech Market Has Potential to Surpass Japan’s Due to Larger Agricultural Output In order to protect local rice farmers, the Japanese government set a strict rice import regulation, limiting tariff-free rice imports to around 770,000 tonnes annually (less than 10% of domestic consumption), as per Nikkei Asian Review. Out-of-quota rice imports face a hefty import duty of JPY 432 (USD 3.09) per kg, over 20% higher than the local farm-gate price. This discourages additional imports of foreign rice and increases Japan’s reliance on domestic rice production. Nevertheless, the ageing of the Japanese population and urbanisation has reduced the country’s farming population, causing the country to strive for higher agricultural efficiency. According to news provider The National, Japan has been using UAV technology in agriculture since the mid-1980s to dust crops. Today, nearly three-quarters of rice production in Japan is mechanised, while over a third of rice farms deploy pesticide spraying via drone technology, as reported in South China Morning Post. Currently, some of the big names in the Japanese agricultural UAV market include Kubota, Yamaha, and SkymatiX, a joint-venture between Mitsubishi Corp and Hitachi. Meanwhile, Nileworks, a Tokyo-based venture with Sumitomo Corp, the Japanese National Federation of Agricultural Co-operative Associations, and the Norinchukin Bank among its investors, is planning to enter the market in 2018. It could be argued that, due to the early and wide adoption of AgriTech, Japan was able to achieve the highest rice yield per rai in Asia of 774 kg per rai in 2016. Furthermore, in light of a declining trend in the agricultural workforce in Japan, Japanese research company Seed Planning predicts the crop-spraying drone market in Japan to expand at a CAGR of 59.8% during 2016–22E, reaching JPY 20.0 billion (around USD 180 million) in 2022E. Depending on the rate of technology adoption, Thailand’s agricultural drone market has the potential to be worth even more than Japan’s in the future, as Thailand’s production volume of rice was four times Japan’s in 2016. |

|

Big Farm to Enhance Cost-Effectiveness of Technology Adoption for Small-Scale Farmers and Drive Potential Market Value to Match Japan’s To date, it is evident that most adopters of AgriTech in Thailand are large corporations engaged in large-scale farming. Betagro Group, CPF group, and Mitr Phol Group are among those reported to employ AgriTech, with PA technology being the most popular. PA technology enables farmers to accurately collect and process biophysical, weather, and farm data to optimise production. Mitr Phol Group, Thailand’s largest sugar producer (accounts for nearly 20% of the country’s total production capacity) is currently the only corporation reported to adopt PA UAV technology in the form of surveillance drones to obtain satellite images to monitor sugarcane productivity. The adoption of AgriTech remains minimal amongst small-scale farmers, as the cost of adoption remains too high to make it cost-effective for small-scale farmers, given their limited production. According to Kasikorn Research Centre (KRC), the cost of agricultural UAV in Thailand in 2015 was around THB 300,000-500,000 per drone. As per our previous analyses, if using agricultural drones could cut production cost by 20%, net profit per tonne of major rice produced in 2015 would have increased to THB 1,293. Therefore, in order to make the purchase of the most affordable drones cost-effective for farmers in 2015, they would have needed to produce at least 232 tonnes of major rice (THB 300,000/THB 1,293); this would have required at least 462 rai of cultivation area (yield of major rice in 2015 after a 20% increase: 502 kg/rai). Currently, around 43% of farmers in Thailand operate a farm smaller than 10 rai, while around 25% operate a farm between 10 and 20 rai, making it impossible for most farmers to have achieved that level of production. However, KRC predicts that the price of agriculture UAV in Thailand will drop at a CAGR of around 20–25% between 2017–22E, bringing the price down to THB 67,000–106,000 per drone by 2022E. Assuming that net profit per tonne and yield per rai remains the same in 2022 as in 2016 at THB 1,413 per (latest available information), farmers would only need to produce a minimum of 47.4 tonnes of major rice (nearly a fifth of 2015’s) to make purchasing the most affordable agricultural UAV cost-effective. While this would still require 90 rai (yield of major rice in 2016 after a 20% increase: 525 kg/rai) or cultivation land, the Big Farm project could be the key to solving this problem. Under the government’s “Smart Farmer” initiative, the Big Farm project encourages farmers in the same agricultural field to integrate their land (to a minimum of 100 rai) and for it to be managed by the district agricultural chief officer, in order for farmers to share costs and increase production. As this method would make AgriTech adoption more cost-effective for small-scale farmers, the government encourages the employment of agricultural UAV technology for participants under this scheme, as per Thansettakij newspaper. In 2016, 1.47 million rai of agricultural land around the country (less than 1% of total agricultural land) have been entered into the project for integration, of which around 70% comprised rice cultivation land (1.05 million rai). According to the Department of Agriculture Extension (DOAE), the project aims to increase the area of rice cultivation under the project at a CAGR of 78.2% to 19.4 million rai in 2021E (27.7% of total rice cultivation area in Thailand in 2015). Therefore, by 2022E, it should be cost-effective for all rice farmers under the Big Farm project to adopt agricultural UAV. Consequently, KRC expects Thailand’s agriculture UAV market to expand at a rapid CAGR of 52.7% during 2017–21E to THB 5,915 million (USD 181.0 million) in 2021E, driven by a predicted fall in the prices of devices, coupled with an expected rise in agricultural land under the Big Farm project. This implies that the value of Thailand’s agricultural UAV market would be on par with Japan’s crop-spraying drone market by 2021E. |

Source: Kasikorn Research Centre |

|

In addition, the Thai government is making efforts to provide financial aid to small-scale farmers. In May 2017, the Bank of Agriculture and Agricultural Co-operatives (BAAC) revealed a plan to increase the ratio of agricultural SME loans to 40% by 2020 from 3% in 2017 (as of March 2017). To achieve this, the outstanding loans of farming SMEs must reach THB 400 billion by 2020 from THB 48 billion (as of March 2017). Therefore, while large corporations remain key users of AgriTech at the moment, it is likely that Thailand will see a rapid increase in the adoption of AgriTech by small-scale farmers in the coming years. |